AI-based emotion recognition tech: China's mould for the 'new' socialist?

Chinese modernisation has been described by generations of CCP leaders and civilians as both an intellectual and moral project. Both concepts are conveniently subjective.

In the early 20th century, student protestors behind popular uprisings, like the May Fourth movement, demanded that science and democracy become the main ingredients in China’s post-dynastic recipe for development. Maoist China, an outlying era which explicitly deviated from the pursuit of western modernity, was as opposed to intellectualism as to individual morality—the ever-shifting Maoist doctrine could make adherence to a personal moral code a lethal pursuit.

Decades since reform began in the 1980s, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) recalibrated implementation of its moral and intellectual/scientific objectives, such that the “correct” morality is enshrined in Chinese law, and intellectual nationalism and technological advancement go hand-in-hand. When describing industrial and technological development today, politicians speak as though they are ticking off a series of anticipated historical milestones.

Political predetermination thrives because the CCP functions atop a foundational teleological goal: cultivating an harmonious society, where no conflict does or could exist. Much of the state’s political and legal efforts are designed to realise this. Achieving this goal requires crafting morally upstanding and economically productive individuals—an updated version of the “new socialist man” envisioned in the 1950s, cultivated through a combination of positive propaganda and gruelling thought reform.

Identifying feelings, based on how they appear on faces, is a preliminary step to corralling their more invisible and important antecedent: thought. In the 1950s, observers argued that CCP leaders deem “all errors in action...traceable errors in thinking.” More recent policies, especially in surveillance and re-education through labour, crudely demonstrate how that belief still holds.

Emotion recognition technology might be uniquely suited to expedite the moulding of ideal subjects. If thoughts are behind actions and feelings are behind thoughts, detecting and guiding feelings, especially those of schoolchildren, may result in a “correct” moral cultivation from the start.

“The CCP’s goals with respect to ethics in AI would be on the grand scale—led by concerns that AI will exacerbate the inequality gap and lead to increased protests and instability,” Jeff Ding, University of Oxford PhD candidate and Stanford University researcher, told us. The CCP’s ethical concerns regarding AI do not centre on restricting their own access; rather, officials worry that increasing economic inequality amongst people might lead to more protests. (Protests and strikes are frequent occurrences in mainland China.)

Ironically, the surveillance technology itself has spurred popular criticism.

Smart eyes: Testing and pushback

An Article 19 report by researchers Shazeda Ahmed and Vidushi Marda, published earlier this year, argues that emotion recognition technology is both unreliable and in direct conflict with international human rights standards—amongst other objections. The report focuses on instances of emotion recognition technology used in certain classrooms (as well as public security and traffic safety), where students are aware that their emotional cues are being tracked.

Emotion recognition hinges on the existence of a menu of recognisable human emotions—already considered an inaccurately restrictive way to perceive the complex experience of being human. On the basis of both technical inaccuracy and moral concerns, the authors recommend the suspension of emotion recognition technology in China and the rest of the world.

Ahmed and Marda discuss a concern amongst Chinese academics that students subjected to emotion recognition in schools will develop “performative personalities (表演型人格).” The report describes how implementation of emotion recognition at a school in Hangzhou affected attitudes toward learning, quoting one student who said, “Ever since the ‘smart eyes’ have been installed in the classroom, I haven’t dared to be absent-minded in class.”

But being absent-minded and acting absent-minded are distinct. The report continues: “Some students found staring straight ahead was the key to convincing the system they were focused.”

“We made a point of showcasing the critiques where Chinese educators were saying they don’t know what’s going to happen to students in the long-term,” Shazeda Ahmed, PhD candidate at the University of California, Berkeley’s School of Information, said. She added that the Hangzhou school’s suspension of emotion recognition in classrooms, in response to complaints, was the example of emotion recognition most widely written about in Mandarin.

“I think it’s important to emphasise not only that it got derailed, but also what happened to derail it? Beyond a description of the technology itself, how did it affect the students, parents, and teachers—the people?” Ahmed continued.

The concept of AI-enabled emotion recognition, philosophically in the same vein as predictive policing (used in China and elsewhere), aligns with the longstanding CCP principle that thoughts and feelings can be corrected, rendering problematic behaviour impossible to carry out.

“Any use of emotion recognition in these settings violates human rights,” Ahmed said. “It could take our lifetimes to get every harm into a UN charter—we should talk about those potential problems without being beholden to existing human rights frameworks alone.”

Ahmed and Marda’s report found companies that linked the Maoist norm of the “fengqiao experience” (枫桥经验), where citizens reported each other’s political misdeeds to authorities—and contemporary surveillance mechanisms, such as emotion recognition. In both eras, CCP leaders maintain the belief that ideal citizens can be constructed—or, in contemporary tech vernacular, “optimised.”

Ding described a similar wave of pushback against facial recognition cameras, citing a CCTV report that exposed widespread use of these cameras to collect shoppers’ data without consent (the number of facial recognition cameras operating to date in China is over 100 million, per one interviewee in the report). “That triggered a lot of grassroots backlash against facial recognition cameras being used in public spaces and led to some retailers taking away their cameras,” he said.

Referencing a survey conducted by researchers at Freie Universität Berlin and the University of St. Gallen, Ding pointed out that while Chinese users are more trusting of the government with personal and facial image data, they’re less trusting of companies than Americans, Germans, and Brits.

“That degree of differentiation is important,” he said. “It speaks to two different types of privacy: protection from private company abuse, versus civil rights protection against government surveillance.” This divergence in perspectives, he added, is partly to blame for the misconception that Chinese people are apathetic about privacy. A powerful agency—whether a multinational corporation, the CCP, the US government, or some combination—is likely collecting the data you unwittingly shed at the grocery store.

A more apt approach to data privacy might be to de-nationalise characterisations of popular attitudes toward AI. Instead, governments and companies might consider operating under the assumption that most human beings would rather have the opportunity to provide consent before data—particularly personal biometric data—is collected and shared.

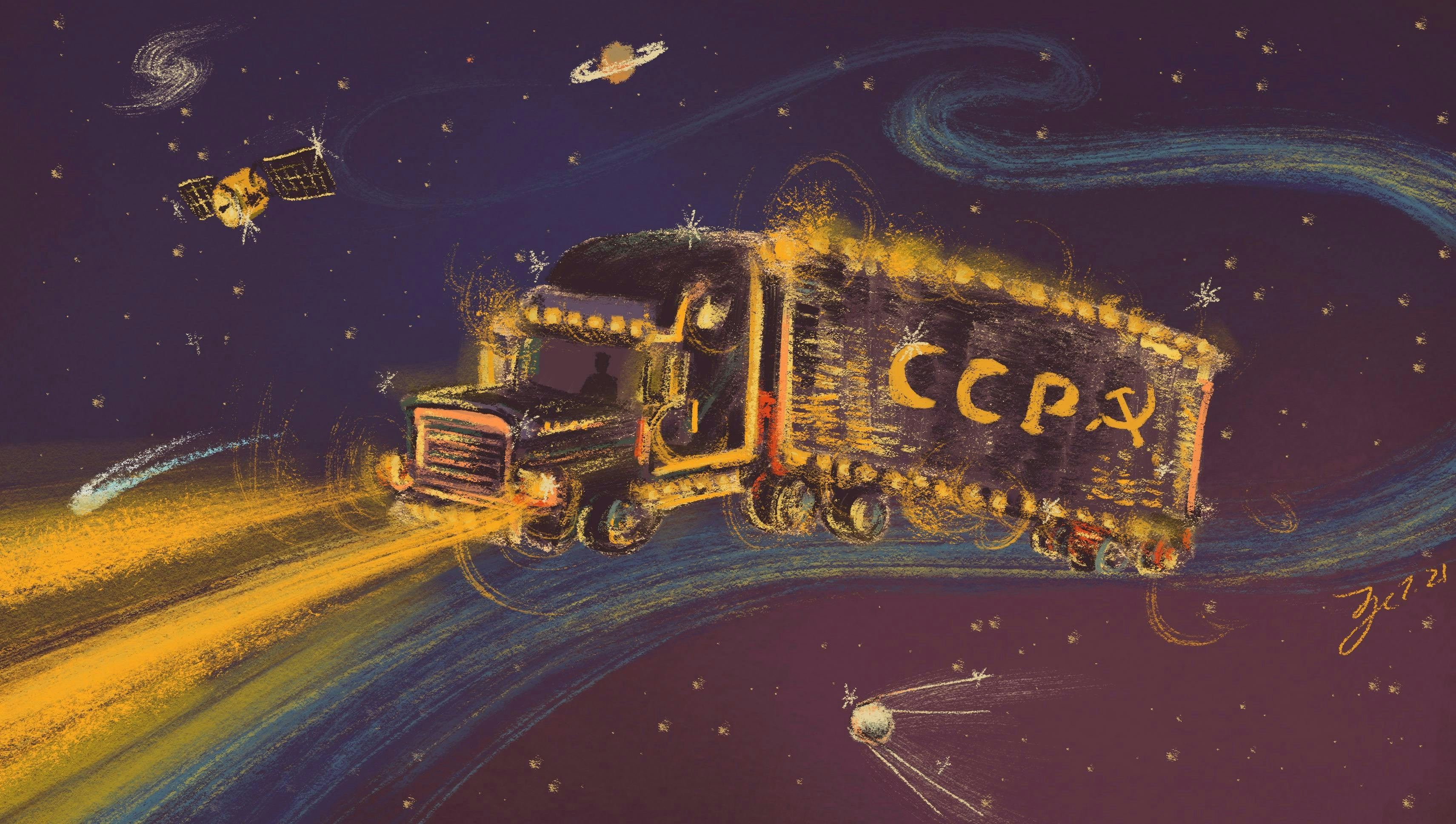

A very different kind of Magic Schoolbus

Export the tech, maintain the politics

According to the Article 19 report, widely acknowledged flaws of emotion recognition technology have not blunted optimism about its potential: “Emotion recognition technologies’ flawed and long-discredited scientific assumptions do not hinder their market growth in China.” Since the market has not managed to address the highest form of biometric intrusion currently in use, regulation is advisable.

Chinese authorities want to be on the ground floor of any such regulation; official documents signal active debate amongst both industry experts and CCP leaders regarding AI's ethical bounds of. Unsurprisingly, though insufficiently recognised by English-language writing on the subject, there are different opinions on how technology should be used in designing economic systems and state-society relations.

The government’s desire to lead in AI standard-setting offers a window into the philosophy of some of the most successful arguments, like enhancing privacy and personal data security (present in the Personal Information Security Specification) to follow a vaguely defined ethical standard.

Earning public trust is central to China’s 2018 white paper on Artificial Intelligence Standardisation, a government document from the Standards Administration. Trust is portrayed as prerequisite to the technology’s progression: “The public must trust that the security benefits that AI technologies can bring to humans far outweigh the harms. Only then is it possible to develop AI.” The paper also states that “protecting personal privacy is an important condition” in the process of procuring social trust.

Bias in AI design is addressed, but an antidote is promptly presented: “It is necessary to ensure that the design goals of AI are consistent with the interests, ethics, and morals of most humans.”

The method by which any individual, company, or nation might deduce the “ethics and morals of most humans” remains unspecified. Considering the ongoing ethnic disparities in the use of surveillance and other coercive technologies in China, this could be a shorthand for the official ethics, crafted by Han leaders of the CCP. These “morals” are cemented into law and governance through legal actions and campaigns, such as the Socialist Core Values, which codifies values like “harmony” and “friendship” into law.

Despite persistent coverage of China’s attempts to export digital authoritarianism, Ding does not believe shipping out AI capabilities is at the top of the CCP leadership's to-do list. “Exporting the digital surveillance model doesn’t necessarily serve the primary needs of the party: Economic prosperity for stability maintenance and national security.”

Implementing these technologies domestically, however, does contribute to central Party interests.

Ding noted that some Chinese tech companies have leveraged the Belt and Road Initiative, a PRC-led global infrastructure development program, to push projects forward internationally. “There’s definitely a vector of influence from there,” he continued. “But this is a long causal train of processes. It's not just that you buy a Dahua facial recognition camera and become a surveillance state overnight.”

Modernisation Through Surveillance

China has a long history of collecting large quantities of personal data. Among the pre-digital CCP’s first projects, after assuming power, was a census. These days, as seen in the smart eyes tests and widespread use of facial recognition, digital collection of personal data occasionally engenders societal resistance. A tensionless society has not yet been realised.

On the other hand, AI may be smart ... but it is decidedly not—and might never be—mature enough to reliably distinguish between complex emotions. If we had to bet on who would be better equipped to understand the psychological and academic needs of students, for example, we would perhaps bet on teachers, not smart eyes. Unlike humans, AI has no way of knowing how easy it is to fake a smile.

To "improve" citizens, officials must understand them as they are. But as digital data collection techniques continue to scale, the CCP sees itself on-track to achieve a harmonious society. Steering the country to the right destination is what matters; the path is secondary. Though if an harmonious society were achieved in full, of course, the necessity of CCP leadership might come into question.

This article is part of a series about the People's Republic of China and its relationship to technology. Previous pieces appear below.

24 Sep 2021

-

Johanna Costigan

Illustrations by Frankie Huang.

DATA-DRIVEN TECH & SOCIAL TRENDS. DISCOVERED WEEKLY. DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX.

02/03

Related Insights

03/03

L’Atelier is a data intelligence company based in Paris.

We use advanced machine learning and generative AI to identify emerging technologies and analyse their impact on countries, companies, and capital.