You don’t own me! ‘Made For Love’ and our increasingly data-driven relationships

TOPICS

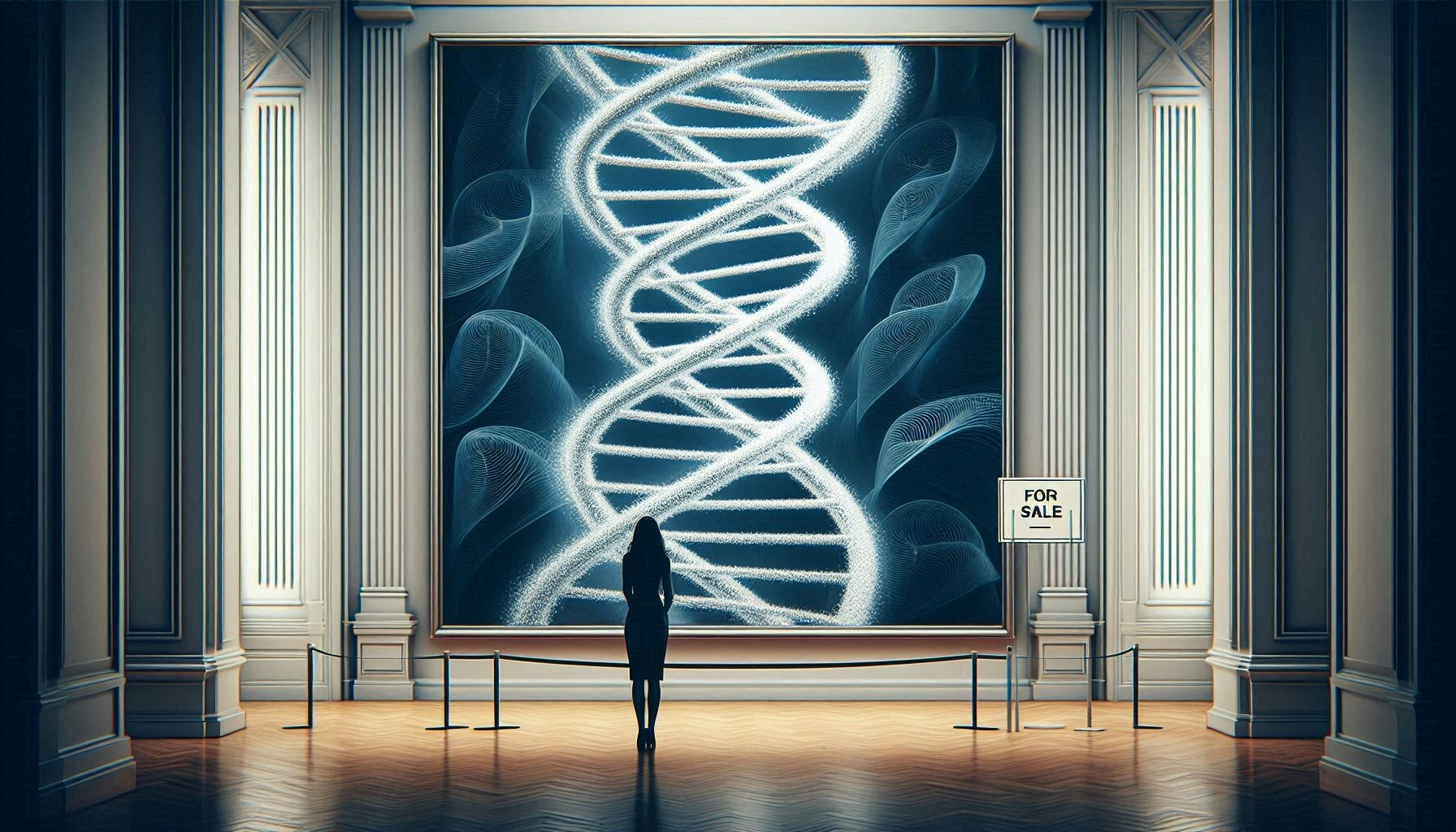

Data and PrivacyData, access, privacy, and rights are interdependent. More than ever, we willingly trade our data and privacy, even highly-sensitive personally identifiable information, for the promise of convenience or simplicity.

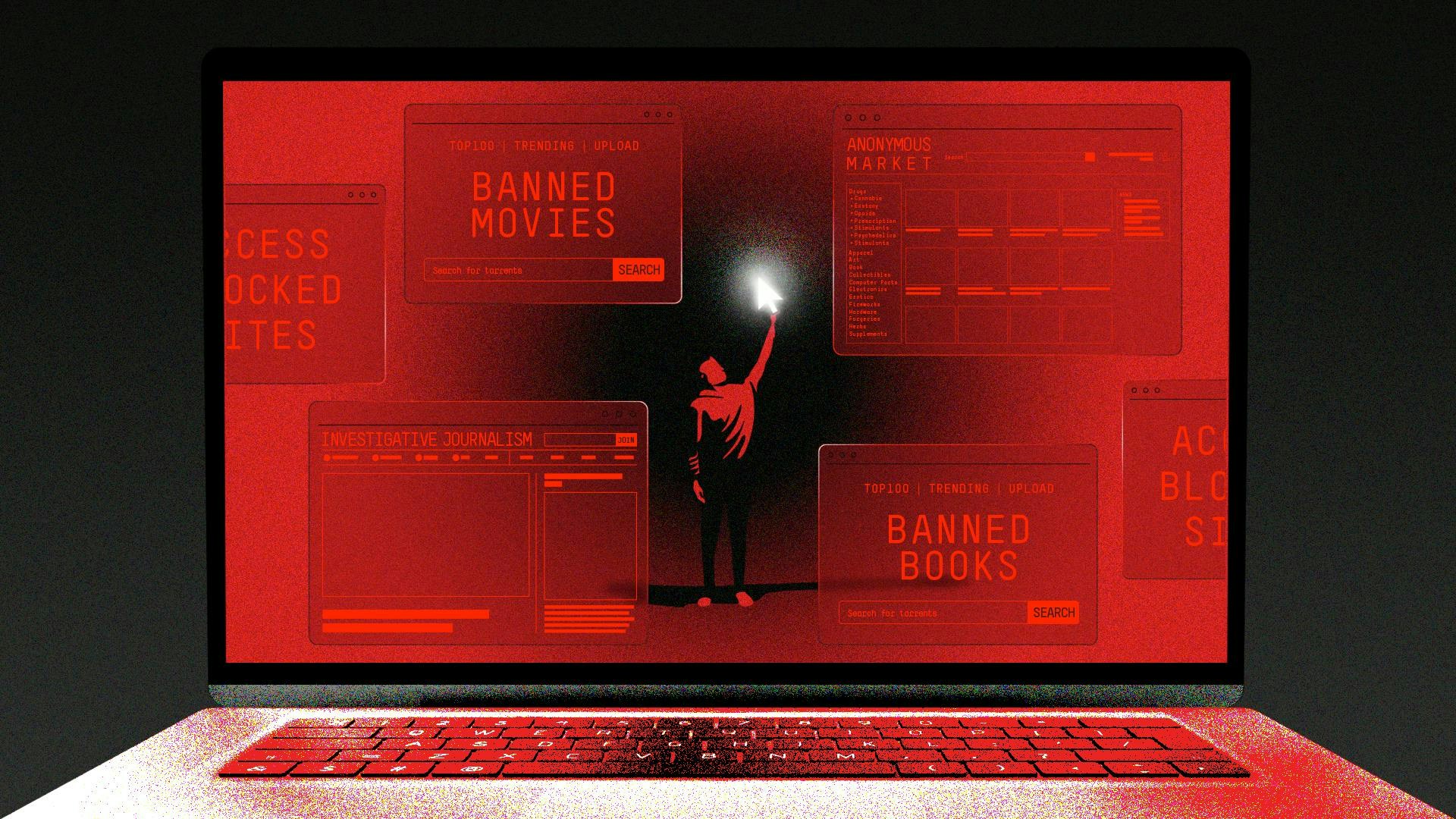

Through expressly-granted permissions, checkbox acknowledgements, and Terms and Conditions, whenever we install software applications to phones and computers—and those smart devices that are always listening at home—we enable access and use of our data. According to Pew Research, about three in ten Americans (28 percent) say they benefit when companies collect their data, so some of us are fine with this.

But frequently, those limited-access data rights we grant are exploited.

To wit: Google Home’s Mini Smart Speaker “[intercepted and recorded] private conversations in homes without the knowledge or consent of the consumer,” according to Consumer Privacy Organisations. Similarly, in connection with a murder investigation, an Amazon Echo became the subject of a search warrant seeking “electronic data in the form of audio recordings, transcribed records or other text records.”

Joel Reidenberg of Fordham Law says, “Under the Fourth Amendment, if you have installed a device that’s listening and is transmitting to a third party, then you’ve waived your privacy rights. The legal standard of ‘reasonable expectation of privacy’ is eviscerated.”

Then there’s outright theft. When the privacy partition is breached, when corporations and government entities exploit authorised data access, and when bad actors gain unauthorised control, the value and vulnerability of our data is immediately crystallised in our understanding. Together, these powers—data, access, privacy, and rights—hold sway in our day-to-day lives.

Increasingly so, in a not-too-distant future.

The HBO Max Original miniseries Made for Love foreshadows these unspooling virtual worlds we passively cultivate. The show is based on Alissa Nutting’s darkly comic sci-fi novel by the same name. (This article contains light spoilers and is not recommended for people who don’t like that kind of thing.)

The birth of a technological love story

Made for Love, now pending a second season, is dominated by “all of these ideas that, for decades, we’ve thrown out as outlandish, which have not only come to pass but are also relatively normalised”—virtual realities, automation, artificial intelligence, robotics, and more, says Nutting, a creative writing professor-turned-film and TV writer. (Her current work in progress, Teenage Euthanasia, is an adult cartoon set in near-future Florida.)

Nutting was in middle school in 1983 and ‘84, when AOL and Prodigy appeared on the scene. “It was just this really unregulated time,” she recalls in a recent interview. How chat rooms and private messaging worked—how users connected generally—were mysterious concepts. “People were only beginning to figure it out.”

Still, she says, there was no real fear about potential downsides of the new technology. Compared to now, there was relatively little to lose in terms of data inventory. Risks seemed insignificant on the balance against innovation.

The internet was technology, and technology was an educational tool, so “it wasn’t something [my parents] were thinking about monitoring.” Her much older siblings meant she had a kind of only-child experience. Nutting describes her parents as conservative today, overtly religious as she grew up. “They were very very Catholic—specifically, around any issue of sex or sexuality—and very much over parenting.”

Laughing, she adds, “I was a Catholic accident,” and the internet was her escape hatch. Tech provided a workaround for parental censorship. “I began having conversations with adult men, activating all of these feelings of romantic love, and kind of crossing all of these boundaries that felt new and exciting.”

So for Nutting, ideas and experiences with internet technology, and romantic love, were linked themes in her formative years. “If the internet and chats hadn’t come [into my life] when they did, I think I’d have a much different feeling about relationships,” she says. “But this thing was really more of [...] an invasion, a telescope, a lens, fixed on your life, by someone that you maybe no longer want watching you.”

Nutting, now 39, learned that technology, sometimes “lauded as an umbilical cord between romantic partners, is actually a mediating figure that [occupies] a space in relationships.” Tech has a life of its own that extends beyond relationships. In fact, the boundless nature of the internet, and the Internet of Things (IoT), can super-multiply our likelihood of finding love and catastrophe; euphoric, validating experiences, and heartbreak, too. “These were my entry points to the story," the author says.

The IoT, to which we’ve become wedded, is no longer a concept in some faraway Jetsons age. It’s here now, usurping personhood with intimate knowledge, accuracy, and speed that only supercomputing can deliver.

Through technology architects, human creators in life and on-screen, technology is imbued with omnipresence, near omniscience, and a permanence once ascribed to God alone.

Made for Love: A primer

"The future is already here, it's just not evenly distributed."—William Gibson, Cyberpunk

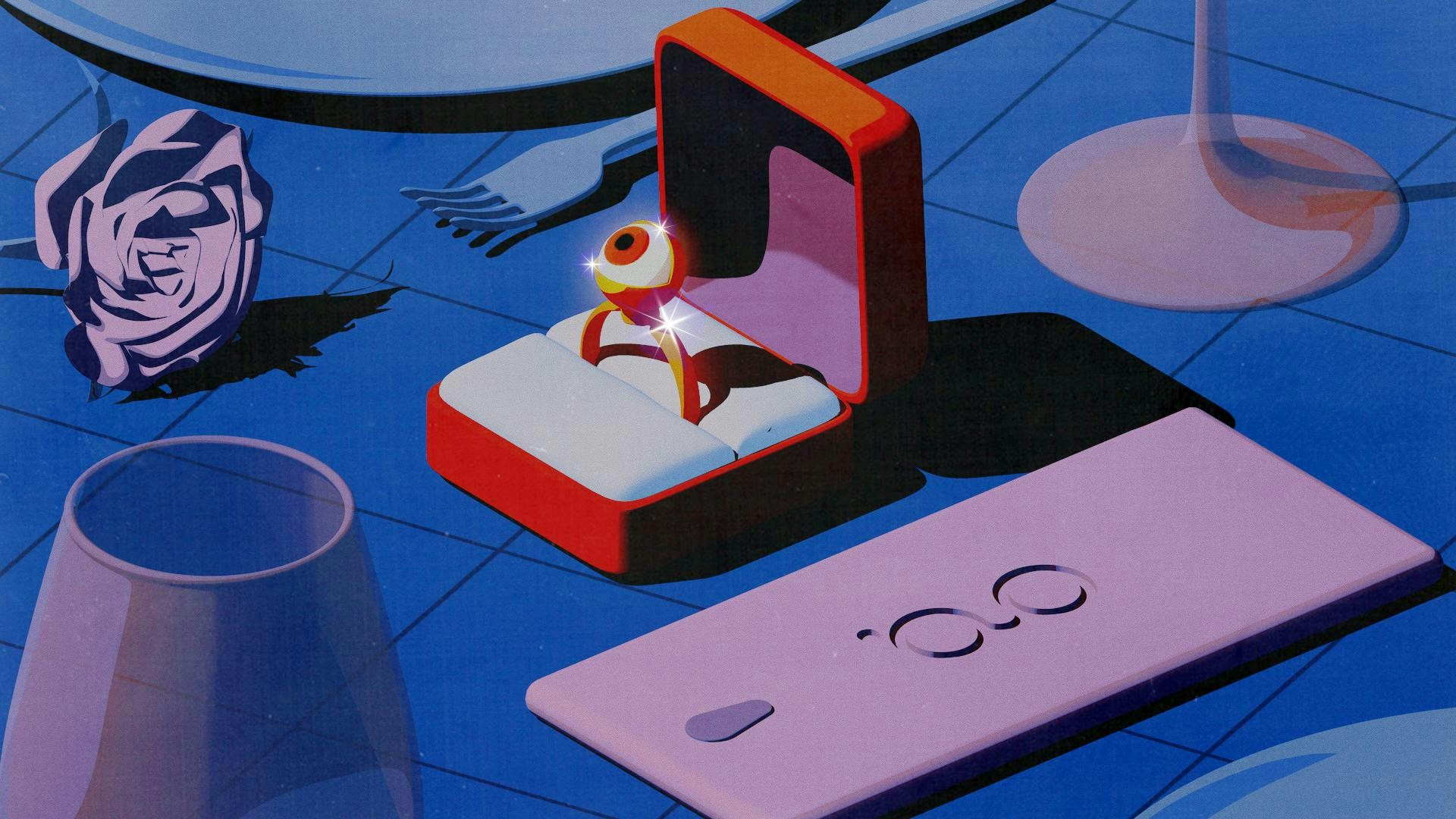

In this tale of hybrid life and landscape, Hazel Green (Cristin Milioti), wife of razor’s-edge tech innovator Byron Gogal (Billy Magnussen), is subjected to relentless layered surveillance—even microchipping—in the name of love.

To further Byron’s plan for “co-mingled minds, co-mingled identities, and pure union,” an unwitting Hazel is implanted with Gogal Tech’s Made for Love microchip, giving Byron access, use, and ownership of her data—every thought, memory, and action. With the immense resources and smart technologies of Byron’s Gogal Tech (a play on Google), she is managed to humiliating granularity. Even her orgasms are scheduled and graded.

Possessing data about a thing is in some ways owning that thing, says Nutting. “Everything about her, even down to these intimate acts that are supposed to be romantic and spontaneous, or unquantifiable, Byron wanted to measure.”

Judiff (Kym Whitley), a nun, says to Hazel, “ He robbed you of your solitude [...] and made himself all-seeing and knowing in your life. That is a relationship reserved for God.” To which Hazel replies, “He took all my hiding places.”

Notably, Byron does this unilaterally; for Hazel, there is no exploration of Byron’s inner being. No reciprocal vulnerability.

Herbert Green (Ray Romano), Hazel’s father—who expresses doubt about his daughter's experience—muses, “As a business concept, who’s gonna choose to put a chip in their head?”

It’s a question for us all: At which point did we opt in?

Nutting evokes a silent alarm.

“When I hear about new tech that sounds either preposterous or overly invasive, I think about [the] frog in water that’s slowly heated and heated and heated until it’s boiling; and the frog, because of the incremental [change], [never coming to awareness], never jumping out.”

Similarly, our behaviour as data subjects often signals a sense of overwhelm and disbelief about the predatory aspects of digital environments. To save time, or for convenience when willpower hits a low point, Nutting says, even she makes the trade.

Nutting calls Herbert a voice of doubt and generational disconnect about what’s acceptable to society, and the ways in which we’re complicit in actively brokering any number of high-stakes deals for potentially favourable outcomes.

After the death of his wife, Herbert negotiates with himself to redefine the terms of his happiness. Missing the qualities and attributes of person-to-person interactions, he opts for the convenience of a unilateral “relationship” with Diane, his “synthetic partner.”

The subtext seems clear: For a happy ending, there may come a time when we all make that sacrifice.

Cybernetics: Where fiction meets reality

In 1998, Kevin Warwick, Professor Emeritus of Cybernetics at Coventry and Reading Universities in the United Kingdom, became the first “cyborg." In that pioneering experience he calls Project Cyborg 1.0, Warwick’s nervous system was implanted with a computer chip. Some years later, in Project Cyborg 2.0, a second device was implanted to his wife Irena’s nervous system.

Warwick believes that, one day, human beings will commonly be upgraded and “optimised” by human-centric implantable devices over an artificial intelligence network. He says his experimentation has proven it’s possible.

With the internet acting as a nervous system, and his body extended “across” it, “We arranged a new form of communication between two human nervous systems," he explained in an email. "In the future, I believe [we’ll] communicate directly, brain to brain, by thoughts alone,” using human and artificial intelligence.

Warwick, 67, hopes the final product will “exhibit the best of both worlds.”

“Co-mingled minds, co-mingled identities, and pure union. Together we will become a single living god.”—Byron Gogal

It may seem strange that humanity, by its own technological invention, could legitimately upgrade itself. Stranger still is the idea that “a cyborg, an ‘upgraded’ human, would ‘naturally’ value other cyborgs more than ordinary humans."

But Warwick’s I, Cyborg (University of Illinois Press) “seriously questions human morals, values and ethics.” He wonders, “If you can communicate by thought alone, what value would you place on the silly mechanical noises that ordinary humans make?”

Comparable questions can be asked of the future he imagines. According to CBS News, “some Christians believe [implantable] devices are eerily similar to the ‘mark of the beast’ as described in the book of Revelation, while ‘singularity’ buffs—those who look forward to the merger of humans and intelligent technology—regard [the devices] as a bold step forward.”

Implications on gender, and other power, dynamics

Made For Love begins as a kind of glass slipper Cinderella story, then quickly morphs into diamond handcuffs—“an invasion, a telescope, a lens, fixed on [Hazel’s] life,” says Nutting, “and another iteration of the power dynamic that’s being calcified in [a] greater and greater space.”

Hazel’s dilemma highlights the vulnerabilities of data sharing, of being “findable,” of visibility—and the advantages of invisibility. “When is invisibility working against you, denying you humanity?" asks Nutting. "When is it a privilege, kind of working for you? When we consider surveillance, invisibility is a kind of power,” says Nutting. “Who gets to hide and who gets to watch?”

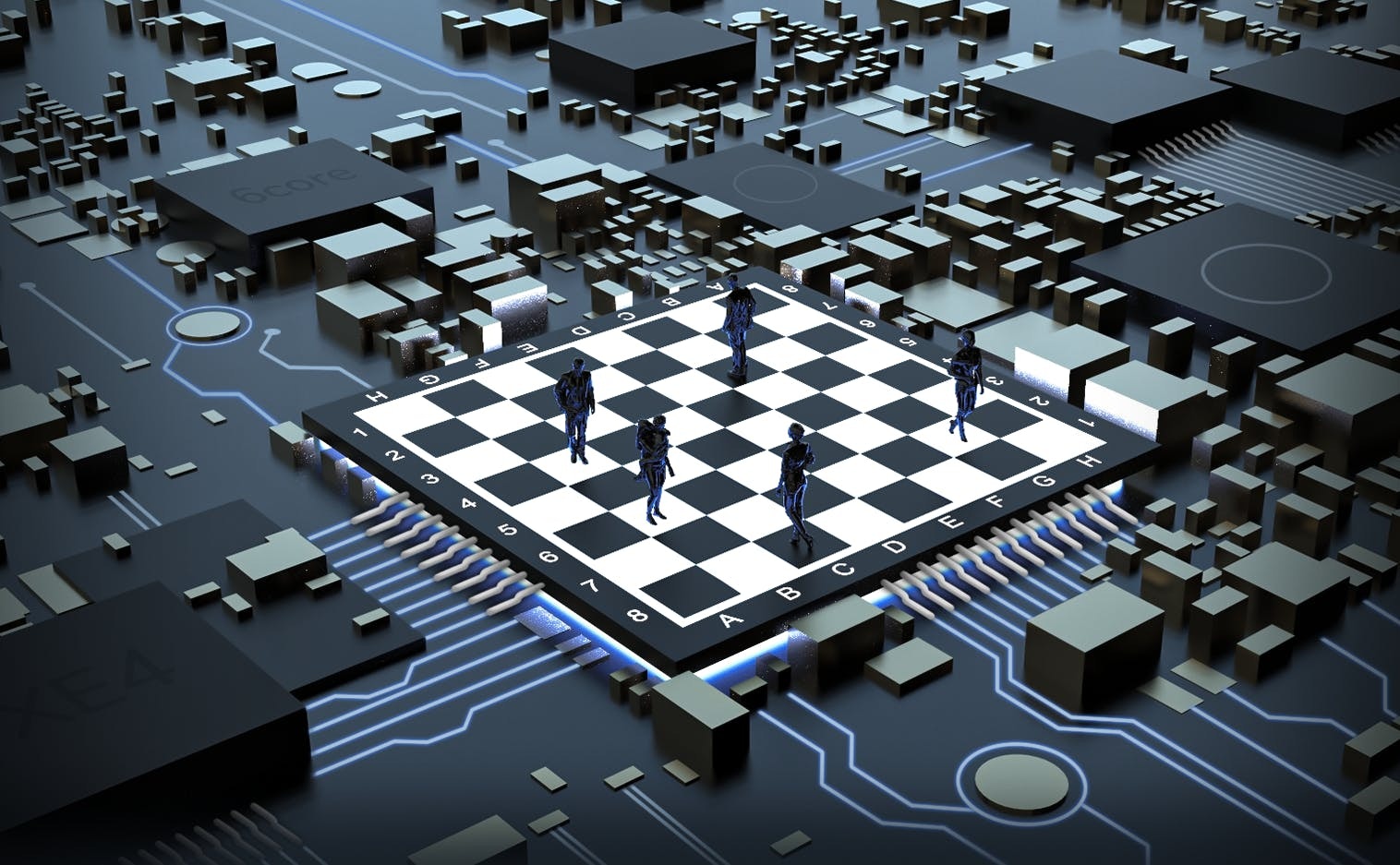

Invisibility can also amplify harm in a gender-based power dynamic where inequities can be hand-carried by machine learning, delivered through artificial intelligence, and manifested in decisions made by “smart” technology.

In one example, David Heinemeier Hansson, founder of Basecamp, disclosed a personal experience in a serial, viral rant on Twitter:

“The @AppleCard is such a fucking sexist program. My wife and I filed joint tax returns, live in a community-property state, and have been married for a long time. Yet Apple’s black box algorithm thinks I deserve 20x the credit limit she does”—the couple files joint tax returns, and his wife has a better credit score. “No appeals work.”

Similarly, Steve Wozniak, Apple Inc’s co-founder, admitted to receiving “10 times more credit on the card, compared with his wife.”

For years, Shankar Narayan, a Seattle University professor of law, has advocated for fair, community-centric technology. He says that, industry-wide, policy and standard operating procedures lay the groundwork for rigorous accountability. But failing to ask the right questions, and demand the right answers from the right people, ultimately brings about public harm.

“There’s a lot of tech solutionism,” says Narayan, a former tech and liberty project director for the ACLU. “‘No matter what the problem is, throw tech at it. It’s gonna get better’.” He observes multiple problems with that approach—primarily that technologies on broken systems generate pernicious effects in the dark, by concentrating power behind walls. “Those walls, whether technology or government processes, [shield] the algorithms that manage and control a lot of these [broken systems].”

Unchecked and unchallenged, “innovative” systems feed upon, strengthen, and reverberate inequities. Technology makers are responsible for the devastating outcomes that can follow engagement with “black boxes,” systems where inputs and outputs can be seen, but how outputs are created is non-transparent.

Narayan says, as a matter of principle, and through his work in privacy, technology, and civil liberties, it became clear that “BIPOC, and other communities at the wrong end of structural inequity, [cannot] just cede that territory. We must engage.”

Next in our convoluted relationship to data...

According to Narayan, our data is siphoned from virtually every website and transaction. By connecting to online systems, doing business, or simply moving around in public, we supply corporations and government agencies with information that further enables their commodification of our private lives. This is exactly why Big Business and Big Government are enthusiastic about cashless societies, he observes.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, and historically in times of global crisis, we’ve hoarded cash. In markets based on supply and demand, this can drive down interest rates, crash economies, and further burden those already at the bottom of society.

In a future piece, we’ll explore factors motivating government shifts from fiat to intangible currency, and the human implications of this “convenience.”

20 Aug 2021

-

Carla Bell

Illustrations by Debarpan Das.

DATA-DRIVEN TECH & SOCIAL TRENDS. DISCOVERED WEEKLY. DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX.

02/03

Related Insights

03/03

L’Atelier is a data intelligence company based in Paris.

We use advanced machine learning and generative AI to identify emerging technologies and analyse their impact on countries, companies, and capital.