Masquerade Over: The Repercussions of Social Media Gatekeeping

TOPICS

Social MediaA conversation, sometime in 2025...

Me: I can’t believe that you haven’t seen President Harris’s speech about how she will tackle climate change.

My friend: Where did you see it?

Me: Twitter.

My friend: Twitter...? I forgot you're such an old-school leftie!

A year ago, this (imagined) conversation would have made sense to a lot fewer of us. Whilst preferences for certain traditional media tend to signal strong political affinities, new media companies largely managed to avoid being labeled thus, on the grounds that they provide generic access without favour to content.

Regardless of whether we believe these claims, the editorial choices that social media companies make on every day have never been so relevant to the public agenda. The decision to ultimately ban Donald Trump’s social media accounts, starting with Facebook and Twitter, is among the most prominent examples.

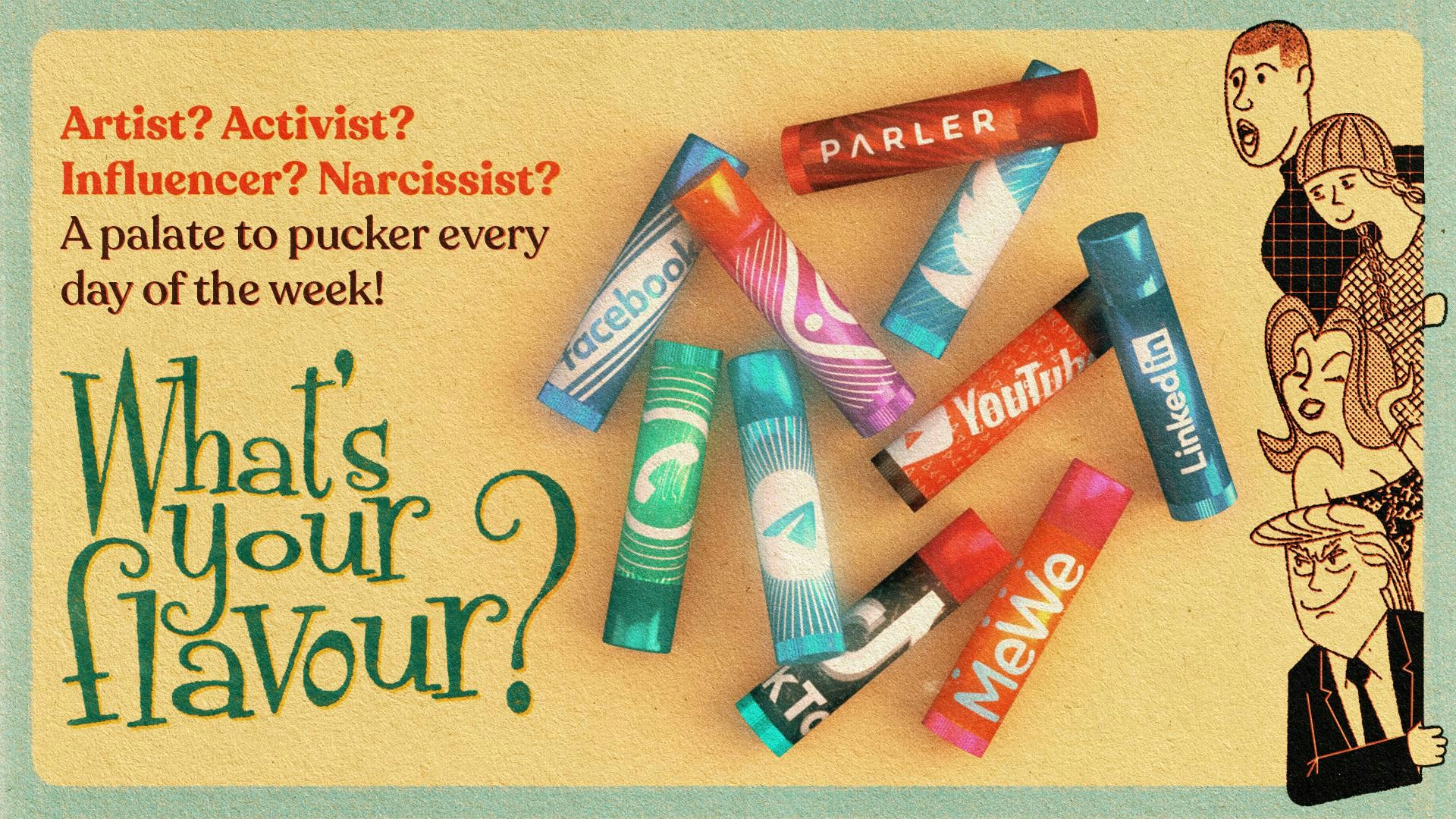

The two social media giants were not the only ones at the centre of attention. During that same period, Amazon withdrew hosting services from Parler, a right-wing alternative social media app. And Apple was sued for not pulling Telegram, a privacy-focused messaging app, from its store, because of its alleged use by those who attempted to seize the American Capitol.

While these moves were the cause of joy to some and outrage to others, at a deeper level they herald an important new chapter in the role of new media—one where the latter must embrace its role as gatekeeper of information and access to content.

Why now?

The viral nature of COVID-19 misinformation, combined with rapid and coordinated action by governments to safeguard public health, triggered the first wide-scale interventions by digital platforms. Of course, misinformation has been a particularly difficult type of harmful content … as we have all come to learn over the last 12 months.

When Facebook became the first social platform to decide to prioritise feeds from friends over media outlets in 2016, the entire industry opened up to the easier spread of misinformation. It hasn’t helped that much of the information shared on our feeds has been automated.

For instance, according to Professor Kathleen Carley (Carnegie Mellon University), between 30-49 percent of accounts tweeting about Black Lives Matter in the US, after George Floyd was killed, were bots. Much of this activity focused on spreading conspiracy theories and disinformation—including the claim that his murder was a hoax.

Such situations place increased pressure and responsibility on digital platforms, businesses, media outlets, and other agents of digital knowledge production to employ solutions that protect us from fakes. For the first time, Facebook, Google, Twitter and TikTok partnered with a major international organisation, the World Health Organization (the WHO), to tackle false information about Covid-19. In the case of TikTok, this involved streaming chats with WHO experts. Google drastically intervened in how search results are displayed whenever anyone uses a term related to the coronavirus—pushing verified or official content, instead of relying on its own search algorithms.

In doing so the search engine has—also for the first time—acknowledged its inability to effectively stop harmful content, not to mention tacitly accepting its role as an information gatekeeper: Its model is based on controlling and limiting access to information, as much as on broadening it.

Platforms have always used gatekeeping techniques, such as Twitter's "Trending Topics feature," to amplify some information sources over others. Labelling a news item as trending increases the gap in readership between it and less "popular" news items.

This is closely related to the (algorithm-based) online advertising practices that got Google fined €1.49 billion from the European Commission on anti-competitive grounds. Regulators are changing the playing field for digital platforms, and the EU’s recently-introduced Digital Services Act will make bigger players take notice.

The legislation moves away from a voluntary regime, and whilst it stops short from making digital platforms accountable for content, it establishes accountability for what internet companies do with it. With an introduction of fines that could total up to 10 percent of a company’s global revenue, and the ability of regulators to break up technology firms, this new approach has serious teeth.

Some regimes plan to go further. Following the wave of online account restrictions after the US Capitol siege, the Polish right-wing government announced legislation that would restrict technology companies from banning users or content on any other grounds than when something is deemed illegal under Polish law.

The consequences of digital gatekeeping

The changes in the role new media and digital platforms play in society have implications that are farther-reaching than market competition considerations, and the last 12 months may provide an indication of where things are going.

First, we can see that the repositioning of mainstream social media has led to a significant rise in the use of alternative platforms. After Apple removed Parler from its App Store, a text-based Facebook alternative app called MeWe saw 1 million new downloads in just 72 hours. New user numbers also spiked for both Gab, a right-wing alternative to Twitter, and Telegram.

These rapid shifts to alternative social media are part of a wider trend of particularly younger users moving away from mainstream social media platforms—largely driven by concerns about privacy, screen time and authenticity.

Secondly, how wider society uses social media has also shifted. In 2020, many of us started living our private and professional lives online. Take the UK as an example: At the peak of the April lockdown, the time adults spent on the internet increased by between 20-30 percent, depending on age group.

This rise in our online presence was short-lived and did not hold when restrictions were eased. By September, average time spent online returned to pre-pandemic levels across all ages. Yet this temporary increase in our online lives (which many countries are experiencing again in 2021) had a profound impact on how we consume and engage with social media, and internet information sources more broadly.

This is because social media are about more than content sharing. The size and quality of our online networks, as well as the depth to which we interact with them, impact our identity, worth and ability to call on family, friends or colleagues. In other words, social media are sources of social and cultural capital.

In lockdown, this type of social capital rapidly gained importance—whether to help tackle mental health issues or to find our feet at work. Research from the Global Web Index suggested that, after a 40 percent drop in the use of social media for active social connections (since 2014), the pandemic has actually "brought back social media."

But our ability to access social and cultural capital online is highly linked to social background. Those in lower socioeconomic groups use social media in a more limited way, and are unlikely to use platforms most associated with professional contexts. Younger, lower-income users are likely to obtain information from non-new, specific channels (such as Youtube or TikTok videos).

A most tricky game to play

What does this mean for the future?

As social media and other digital content platforms become more inconspicuous about the extent to which they moderate or restrict content, we are likely to see further polarisation of user groups online. Just as the readership of The Sun and The Guardian in the UK represents different social and ideological views, it shall be increasingly difficult to see Facebook and Twitter as “neutral” platforms.

The polarisation of online user groups may become a source of commercial opportunities as online campaigns become more targeted. However, brands will also tread more carefully as the risk of online backlash and other elements of “cancel culture” become more widespread.

The trouble is that, since social media controls access to content as well as to networks, there is a risk that these changes will lead to the creation of an even greater gap between informed elites and “everyone else.” The former will consume social media selectively, but engage with a wider range of outlets, and have a diverse network of online contacts.

But since we know that level of income, social status and age are generally good predictors of how well-informed an individual is, the echo-chambers of social media are likely to reinforce existing social inequalities.

28 May 2021

-

Michal Rozynek

Illustrations by Debarpan Das.

DATA-DRIVEN TECH & SOCIAL TRENDS. DISCOVERED WEEKLY. DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX.

02/03

Related Insights

03/03

L’Atelier is a data intelligence company based in Paris.

We use advanced machine learning and generative AI to identify emerging technologies and analyse their impact on countries, companies, and capital.