Who'll be the 'Netflix of Games'? A briefing on this multiplayer arena

It’s remarkable to consider how much Netflix changed the TV and film industries in such a short space of time.

Beginning in 1997 as a postal service for DVD rentals, Netflix hastened the demise of video rental stores like Blockbuster … but the real sea change came in 2007, when it began streaming films on-demand. By 2013, the rapidly-growing company was creating its own films and TV shows, and by the end of 2021, it had some 222 million subscribers worldwide.

Almost single-handedly, Netflix upended the traditional model for TV and film consumption. The idea of heading to a shop to buy or rent a film, or waiting patiently for your favourite TV programme to air each week, now seems ludicrously quaint, a relic from a bygone era. People expect to be able to watch whatever they want, whenever they want, without leaving the sofa. And the idea of paying individually for each film or TV show seems foolish when Netflix subscribers have an endless buffet of all-you-can-eat viewing for a single monthly fee.

Naturally, other companies followed Netflix’s lead. Services like Disney+ and Hulu, and subscription brands, have become an industry norm, whether you’re consuming anime on Crunchyroll, or gorging on horror movies via Shudder.

Considering how streaming has changed TV-viewing, it’s natural that analysts have long wondered how such services could transform another TV-based pastime: What will the “Netflix for video games” look like?

“The phrase ‘Netflix for games’ has been doing the rounds for so long, it’s reached the point where there are multiple interpretations of it,” notes James Batchelor, editor-in-chief of Gamesindustry.biz, over email.

When we talk about a Netflix for games, do we mean a streaming service like Netflix itself, or a subscription service, where you can access a library of downloadable games for a fee? Perhaps a combination of the two?

Various companies are trying all these approaches. But first, let’s look at the nascent world of video game streaming.

It’s not like telly

Streaming games is more complicated than streaming TV. Whereas the data for a TV show only needs to flow one way—from the remote server to your TV—game streaming is a two-way system, where data must travel at tremendous speeds to make games playable. Each time a player presses a button on their controller, that input must travel for miles along fibre optic cables to reach the server running the game, then the signal travels back along the same cables to the player’s TV to show what effect the button had. This has to happen within fractions of a second, to avoid generating a noticeable lag between performing an action and seeing it represented on screen.

The concept of game streaming has been around for some time. The California-based company OnLive created a set-top box back in 2010, allowing subscribers to stream a range of high-spec PC games. But the service disappeared in 2012 after failing to establish a large enough user base, amid complaints about excessive lag.

Sony bought Gaikai, a rival to OnLive, in 2012, and used its technology to create the subscription streaming service PlayStation Now, which launched fully in 2015. Initially the service was restricted to older PlayStation 2 and 3 games, but later expanded to include PlayStation 4 titles; the ability to download games instead of streaming them was added in 2018.

Yet by 2019, Sony only managed to attract around a million PlayStation Now subscribers. “The company continues to add more titles, advertise it to its users, but it doesn’t really shout about the service in the way its competitors do,” notes Batchelor.

Google enters the fray

The biggest excitement in the world of game streaming arrived in March 2019, when Google announced its Stadia service. The tech giant claimed to have eliminated many lag issues that plagued previous game streaming services, and there was much speculation about how Google’s financial heft and alternative distribution model could upend gaming, as Netflix displaced the traditional gatekeepers of television.

But details of Stadia’s pricing plans, released three months after the initial reveal, dampened excitement. Instead of a “Netflix for games,” whereby a monthly fee would enable access to a huge library of titles, the company said it would sell games individually, at full retail price. A $9.99-a-month subscription option was also offered, but it only gave access to a handful of games for free, and merely gave discounts on others.

“This jars with the way consumers are used to accessing streaming content, with most such services in other entertainment sectors taking the ‘access all content for a monthly fee’ route,” says Batchelor. It didn’t help that the few games ready for Stadia’s launch, like Assassin’s Creed Odyssey and Shadow of the Tomb Raider, had largely been available on other systems for months, and generally cost much less to buy elsewhere.

Excitement over Stadia was further drained by a raft of technical problems at launch—connectivity issues, the absence of promised features, and a lack of exclusive content. A handful of mostly indie games, like Tequila Works’ Gylt, were Stadia exclusives, but no “killer app” drove people to register. Google established two internal studios to make content for Stadia, but too late: Game development takes years, and the studios were only set up around the time Stadia was released.

In the end, these studios didn’t produce any games at all. Just a year after launch, Google announced it would shut them down. This move, along with the technical woes at launch, “soured opinions of Stadia,” says Batchelor, “to the point where it’s questionable whether the service can recover.”

Really, Stadia stalled the moment its pricing system was revealed. Though Google emphasised Stadia’s ability of enabling access to high-end PCs, with games running at 4K and 60 frames per second, years of streaming TV taught us to expect buffering and intermittently slow internet connections, leading to a general perception that streaming is an inferior option to playing downloaded or disc-based content. By suggesting that consumers pay full price for individual games, Google was making a big ask.

Netflix didn’t come to dominate the TV industry by providing the highest-fidelity picture quality. It gained legions of followers by offering the convenience of watching a massive library of titles, many of which are exclusive to the service, for a single, comfortably affordable monthly fee.

Amazon spots an opening

Possibly learning from Google’s mistakes, Amazon entered the game-streaming arena in September 2020 with the announcement of Luna, which follows Netflix’s model more closely. Subscriptions start at $2.99 per month for the “Family Channel,” which offers games for younger audiences, then rise to $5.99 for Luna+, and finally to $17.99 for Ubisoft+, which includes a raft of the latest games from the French publisher.

It’s perhaps little surprise that Amazon took an interest in game streaming, since the company is the largest provider of cloud computing services in the world: It runs around one-third of the world’s cloud infrastructure, followed by Microsoft at 20 percent, then Google at 9 percent.

However, Amazon’s game-streaming service remains in early access, and is currently only available in the United States. “Luna has been relatively low profile since its debut,” says Batchelor. “While there is a decent variety of titles on there from recognisable names—Ubisoft perhaps being the biggest supporter, even including recent releases like Assassin’s Creed Valhalla, Watch Dogs: Legion and Immortals Fenyx Rising—there are no exclusives to speak of, or access to titles or content that players can’t already get on traditional platforms.”

The lack of exclusive titles is a key point. It will be interesting to see whether Amazon starts to promote Luna more aggressively once it leaves early access, securing unique content and perhaps tying it in with other Amazon services, like Twitch and Prime Video. But the company has far to go before it catches up to the current leader.

Microsoft on the warpath

“Is there an ongoing battle to deliver the Netflix for games, right now?” asks Mike Diver, head of content at GAMINGbible. “I'm not totally sure that there is, because battles tend to be over once there's a winner, and it feels like Xbox took this one long ago.”

Microsoft launched Xbox Game Pass in 2017, providing a large range of downloadable games for a single monthly fee. The service has expanded enormously since then. In 2018, the company announced its first-party games would be available on Game Pass on the same day as their retail launch, which dramatically increased the service’s value proposition. For £7.99/$9.99 a month, users can play new games that would otherwise cost $60 at retail, along with hundreds of other titles, including many newly-released indie games.

Damien McFerran, editorial director at Nintendo Life, calls it “something of a no-brainer if you're an Xbox owner—it represents incredible value for money.”

Xbox Game Pass Ultimate launched in 2019, a higher-tier £10.99/$14.99-a-month subscription that combines Game Pass with Xbox Live Gold. The latter allows Xbox players to play online multiplayer titles, and offers free monthly games. In 2020, Microsoft began adding game-streaming options to the Ultimate package.

“Xbox Game Pass is the closest we have to a Netflix for games (so far),” says Batchelor. “It offers a massive library of titles, including plenty of exclusives, some key releases available on day one, and you can access it via a variety of devices: Console, PC, and mobile (via streaming). The streaming system is still not finalised but it has since been expanded to PC browsers and console, meaning players with a Game Pass subscription can instantly play any title on any device, which is very Netflix.” And in a bid to further expand access to its service, Microsoft announced in December 2021 that it was working on a Game Pass app to allow streaming through smart TVs.

“Game Pass is undeniably central to Microsoft’s current strategy,” continues Batchelor, “and ties in with the aggressive acquisition spree the platform holder has been on for the past few years. At first, buying smaller studios like Hellblade creator Ninja Theory, and State of Decay dev Undead Labs, seemingly added more content creators to its portfolio, to ensure a steady stream of new releases for both its consoles and Game Pass. Its deal with Electronic Arts to bring EA Play, the FIFA publisher’s own subscription service, to Game Pass subscribers dramatically increased the value the service offers, and it wouldn’t be a shock to see Microsoft add similar libraries, such as Ubisoft+, to Game Pass in future.”

Furthermore, “its acquisitions have grown much more ambitious with the $7,5 billion takeover of ZeniMax Media (parent of Elder Scrolls and Fallout developer Bethesda) and the almost $70 billion purchase of Activision Blizzard. These deals go beyond just adding new content for Game Pass, although making Bethesda’s hotly anticipated Starfield [an exclusive] is certainly going to make the service even more appealing. Instead, this is adding entire libraries to the service and making the Xbox ecosystem (not just the consoles, but PC and the Game Pass app) something avid gamers will find hard to ignore.”

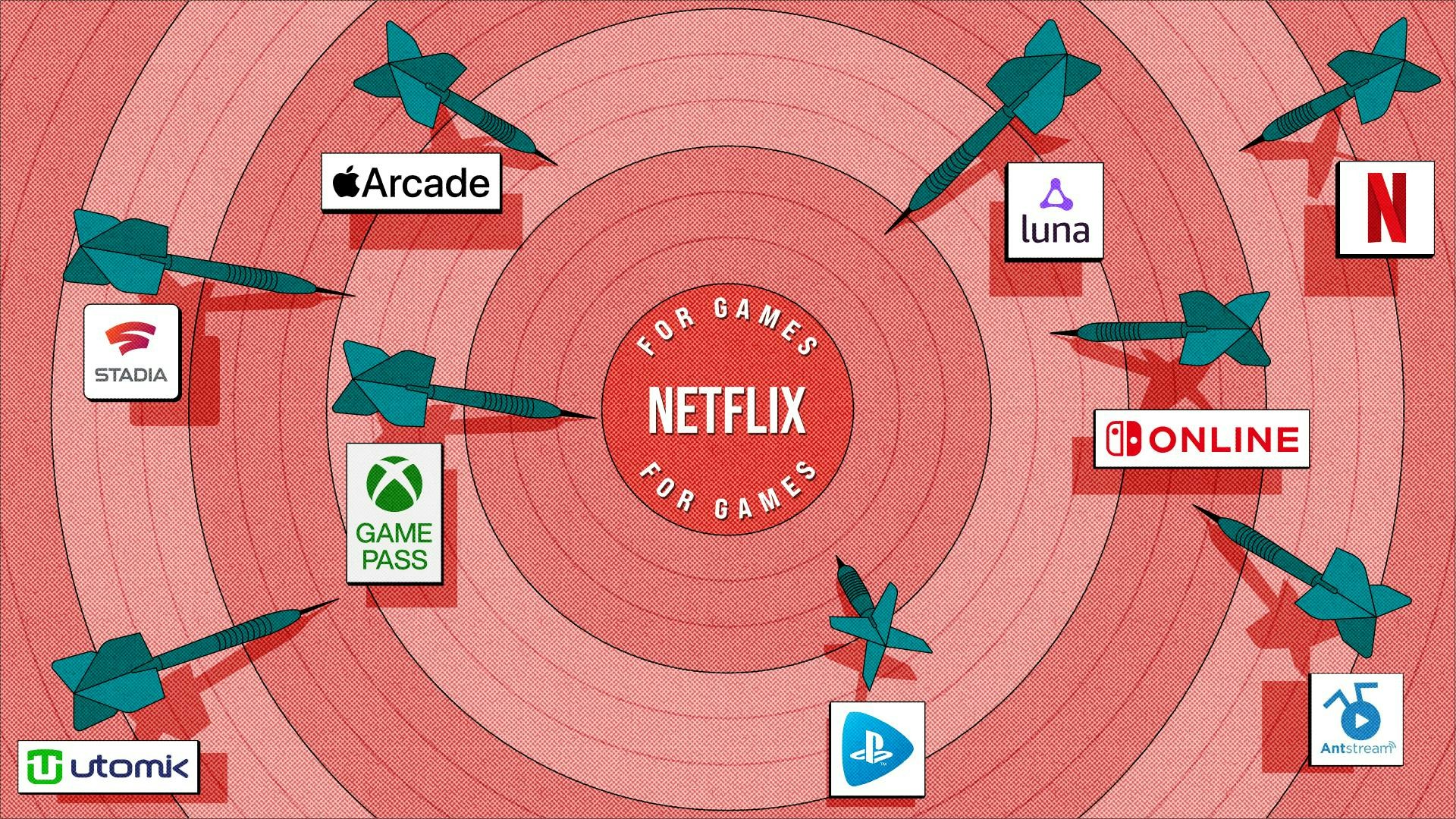

In terms of sheer numbers of subscribers, it seems unlikely that any other company can catch up to Microsoft in the near future. The firm announced it had acquired 25 million Game Pass subscribers as of January 2022, versus the roughly 3,2 million PlayStation Now subscribers reported by Sony in March 2021. “Stadia and Luna have yet to reveal concrete figures,” says Batchelor, “but it’s unlikely they’ve surpassed PlayStation Now and unimaginable that they’ve rivalled Xbox Game Pass.”

Importantly, Diver thinks Microsoft is winning the hearts and minds of consumers. “What Game Pass offers—covering console, computer, and the cloud; a huge variety of gaming genres; AAA releases on day one and some of the most celebrated indies—absolutely eclipses what else is out there,” he says.

“From a value for money perspective, it trashes PlayStation Plus [Sony’s equivalent of Xbox Live Gold], and the less said about PlayStation Now, the better. Looking at our audience and the way GAMINGbible followers react when we post about PS+ additions, there's often dismay that they're not getting value for money; whereas there's definitely growing positivity around Game Pass, which I'm sure will only increase with the Activision acquisition potentially bringing a lot more AAA titles to subscribers on day one.”

Will Sony hit back?

“I'll … bet you all the money in the world that we'll see at least two more major players introduce their own versions of Game Pass this year,” says Mike Rose, director of indie-game publisher No More Robots. “It seems pretty inevitable at this point.”

One such player is strongly rumoured to be Sony. A Bloomberg report in December 2021 suggested the company plans to change PlayStation Plus into a subscription service to rival Game Pass, all while phasing out PlayStation Now. The rumours intensified when Sony began removing PlayStation Now vouchers from retail in January 2022. Diver thinks that if Sony switches the 50 million or so PlayStation Plus subscribers to a Game-Pass-style service, while folding in the PlayStation Now library and adding new first-party releases to the service as they come out, then Microsoft’s lead in the rush towards a Netflix for games could vanish overnight. “It's a big if, but if they could do it, you'd have a ‘battle’ back on, for sure,” he says.

Such a move might be out of step with Sony’s typical stance. Batchelor notes that the Japanese company has so far focused on “the traditional premium games that have helped secure its position as market leader in the console space,” and it has raised the price of PS5 games to $70/£70, citing the increasing costs of developing AAA games.

In a September 2020 interview with Gamesindustry.biz, PlayStation boss Jim Ryan ruled out following Microsoft’s lead of adding new first-party titles to a subscription model on the day of release: “These games cost many millions of dollars, well over $100 million, to develop. We just don't see that as sustainable.” However, when Xbox head Phil Spencer was asked in January 2022 about rumours that Sony would launch a Game Pass-style offering, he suggested it was an “inevitability” that rivals would launch similar services, and said he also expected them to make new games “available Day 1 in the subscription.”

“Sony has such weight in the games space,” says Batchelor, “such a vast library of back catalogue titles and popular IP, that it’s surprising to see the platform holder be so conservative when it comes to subscription services, especially given the noise its biggest rival makes. Sony’s attitude, from the outside, seems to be that it doesn’t need to offer a Netflix for games—but if that changed, it’s well positioned to launch one (and it will have learnings from any stumbles other more aggressive competitors make in the meantime).”

McFerran thinks a change of heart from Sony is a strong possibility. “Out of the ‘big three’ [console manufacturers], I think it's likely that Microsoft and Sony will achieve the dream of a ‘Netflix for games’.”

Speaking of the big three, how does Nintendo fit into all of this?

Nintendo goes its own way

“You'd think Nintendo would be well placed to do their own ‘Netflix for games’,” says Diver, “but they seem oddly reluctant in the Switch era to make any of their older titles easily available, beyond the limited selection they have on the Switch Online service.”

Nintendo offers a range of downloadable NES and Super NES games as part of its $19.99 a year Nintendo Switch Online package. In late 2021, it added Nintendo 64 games as an optional "Expansion Pak" that increases the total annual fee to $49.99. “The move to include Nintendo 64 games there is a step in the right direction,” thinks Diver, “but their doubling of the subscription fee without the carrot of Game Boy or GBA titles to come put some people (including me!) off from expanding their subscription. Because Nintendo doesn't quite feel like it's in the current ‘console war’, and more of a standalone presence with the Switch being such a bespoke system, I expect them to go their own way... which will probably be to still not introduce a new Virtual Console.”

McFerran agrees it seems unlikely the Japanese firm will follow others towards a Netflix-style model. “I'm not sure this kind of service is something Nintendo would look to offer at this stage, as it's still selling games from 2017 at near to full price in 2022,” he says. “There would be little reason for it to change its strategy in the short-term, and its own subscription service is focused almost entirely on offering retro games rather than modern ones.”

Subscription services for the win

Across the gaming world, subscription services are popping up wherever you look. Antstream Arcade is a streaming service that lets users play thousands of retro games ad-free for a monthly fee. Apple Arcade launched in 2019, providing a growing range of premium mobile games on a subscription basis. Utomik offers over a thousand PC games from more than 100 publishers for £5,99 a month. The list goes on.

“Even Netflix is trying to become the Netflix for games,” says Batchelor, referring to the range of mobile games the streaming giant launched in 2021, available to anyone with a Netflix subscription. “That’s not to say Netflix can necessarily rival Microsoft, but the meaning of ‘Netflix for games’ could change depending on where its namesake decides to go.”

Perhaps we’ll eventually stop referring to new subscription services as the “Netflix for games.” But the key point is that they are set to proliferate.

“Even Netflix, while perhaps the leader in its own sector, isn’t the only successful competitor,” Batchelor points out. “If we expect there to be a Netflix for games, then surely there might be a Disney+ for games or an Amazon Prime Video for games. Subscription services, streaming and libraries of content accessed via different business models are almost certainly going to be something the video games industry experiments with over the next decade. All other forms of entertainment have shifted to a model of access rather than ownership, with consumers paying to enjoy as much content as possible rather than (or in addition to) individual purchases, and a similar shift may well take place in the games industry.”

McFerran is firmer in his prediction. “I think it's inevitable that a subscription-based model will represent the future of video gaming,” he says, “just as Spotify and Netflix have done with music and movies.”

04 Mar 2022

-

Lewis Packwood

Illustrations by Debarpan Das.

Stay future-focused with our weekly newsletter.

02/03

Related Insights

03/03

L’Atelier is a data intelligence company based in Paris.

We use advanced machine learning and generative AI to identify emerging technologies and analyse their impact on countries, companies, and capital.