Meet Anthony Kelly, Digital Anthropologist

L’Atelier BNP Paribas is among few companies with in-house digital anthropologists. In this QA, Anthony Kelly explains digital anthropology from his perspective, why it matters, what purpose it serves in companies and for communities … and whose work makes him say wow.

Who are you, how did you get here, and what cultivated your interest in digital anthropology?

I’m Anthony Kelly, director of the digital anthropology stream at L’Atelier. I’m a former lecturer in digital anthropology, with a PhD in Media and Communications from the London School of Economics and Political Science.

I became interested in the field of digital anthropology as an undergraduate, 15 years ago, when I began examining how vitriolic characterisations of political opponents entered the comments section on Yahoo! News. I wanted to understand what relationships existed between those depictions of political difference in online discourse, and the thoughts and feelings of actual people. I felt these forms of opposition might indicate deep-rooted cultural issues, with implications for social cohesion. This was the beginning of an enduring fascination with the interplay of polarisation and partisanship, which became the topic of my PhD thesis several years later: I focused on how American conservatives battled in an online user-generated comment field over whether or not they should support Donald Trump’s candidacy in 2016.

In recent years, we’ve become increasingly aware of the role digital technologies play in reshaping the lives and livelihoods of people, which only underlines the need to examine the transformations associated with digital culture in greater detail.

What is digital anthropology, and how is it different from basic anthropology?

Traditionally, anthropology has relied on doing long-term embedded ethnographic fieldwork, which for a long time meant living within a community over extended periods, often in far-off places. In the digital era, communities and cultures also exist and emerge online, challenging the established toolkit for getting to know people and cultures.

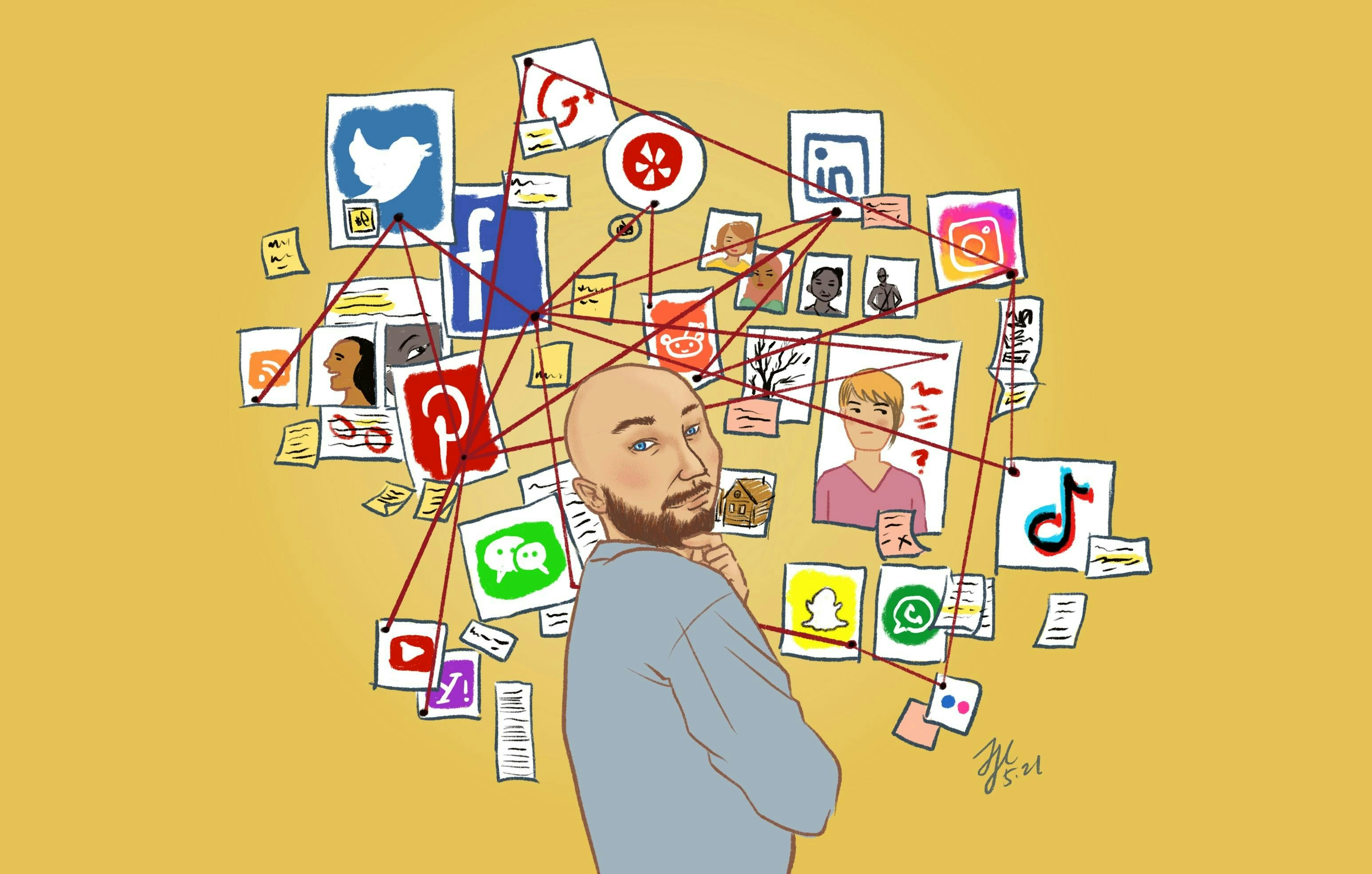

On one hand, digital anthropology is the analysis and critique of the frequently transformative relations between humans and digital technologies. On the other, it’s the study of how human relationships are increasingly mediated and enabled by those technologies.

At L’Atelier, we think of digital anthropology both as the study of the social and cultural implications of emerging technologies, and as a framework for approaching matters of social and cultural significance through digital techniques. Depending on where you look or who you speak to, digital anthropology can be more focused on the material (the things we use) or the communicative (the things we say), among other factors. We try to bridge the two.

Why do we need anthropology, let alone the digital kind?

Anthropology illuminates often profound variations in how different groups of people see and understand the world around them. This knowledge can help organisations navigate cultural differences. By seeking to understand people on their own terms, anthropology allows us to discern competing claims to truth, and how they relate to identities and systems of knowledge. In the context of the epistemic crises that have marked public life in recent years, this orientation towards, and familiarity with, difference becomes a powerful tool for promoting cross-cultural dialogue.

Why does L’Atelier need digital anthropologists?

At L’Atelier we focus on producing insight and foresight on the interface of society and technology. This convergence is the main purview of digital anthropological research. Within the company, we aim to guide the understanding of technological change as an inherently social and cultural process. That means relating our understanding of technology to social context and to the lives of people, both now and in the future. Thus we can centre our understanding on how technological change will impact people and their experience of being in the world, virtually or otherwise.

These factors have broad relevance for the production of insight and foresight on the conditions of social transformations tied to emerging technologies.

What can other companies do with your knowledge?

In broad terms, our research can help companies have a deeper, more nuanced understanding of consumer behaviour, but our contributions go beyond this.

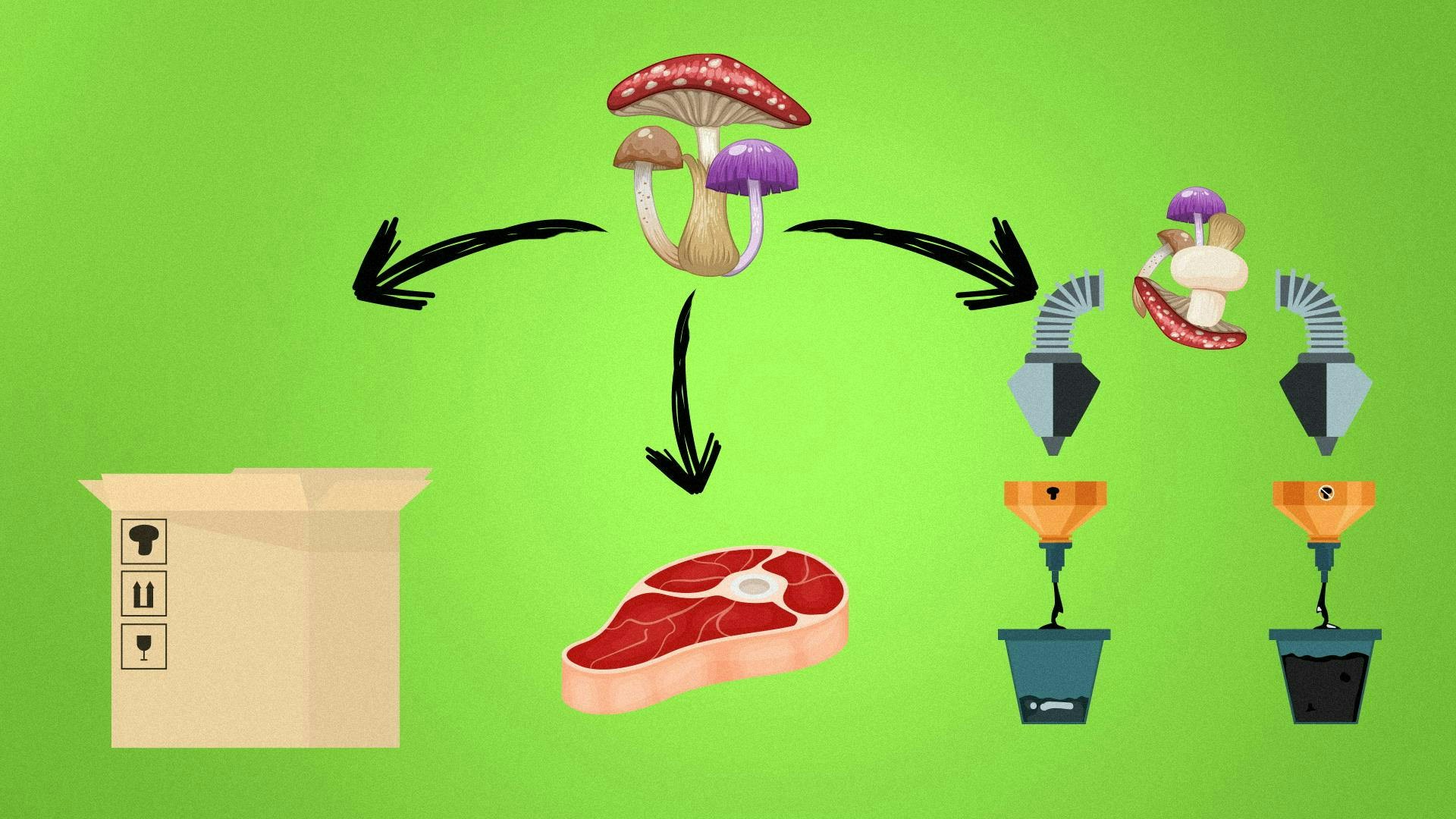

Our main goal is to create greater understanding of the social contexts produced through digital technology deployment. This knowledge can help companies grasp the variety of ways technology can be used, and sometimes repurposed, in ways designers don’t intend.

We also create nuanced understandings of the complex networks of human relationships that characterise our connected moment, including the power dynamics these relationships imply. With this contextual intelligence, we can help companies formulate high-fidelity images of future social and technological environments.

How does digital anthropology impact culture or civic planning?

Digital anthropology is part of a growing subset of disciplines interested in examining the transformation of society through deployed emerging technologies. So we address many questions addressed by critical scholars of digital media, particularly those that focus on the relationships that characterise platforms, digital labour, and evolving global relations of consumption and production.

Through this focus, we contribute to policy discourse at a time when public awareness of the impact of powerful non-state actors is becoming more widespread. Our team seeks to demonstrate how digital anthropological exploration of these, and other pressing topics, can be impactful outside of academia.

Who or what inspires you in your work?

My approach to digital is shaped by my fascination with ways of speaking—specifically how humans use language to mark distinct domains of identity and difference. The work of Michael Silverstein, who died last year and was one of the world’s most influential linguistic anthropologists, is one of my biggest inspirations. He explored the relationship between talk and social context in a way that transformed language study.

Understanding how people use digital technologies is a question of communication. There is a tendency to think of the internet as a space of earnestness and authenticity—people saying what they really mean, or what they really think. The work of Whitney Philips and Ryan Milner disabuses us of that. They highlight an ambivalent internet, characterised not by earnestness but by equivocation, misdirection, and deception.

This perspective influenced my work in political communication, and forms a core tenet of what Nathalie and I do at L’Atelier.

My work at L’Atelier is also influenced by Morten Axel Pedersen’s research in computational anthropology, and the work of his colleagues at the Copenhagen Centre for Social Data Science. Pedersen demonstrated how we can broaden anthropological techniques to incorporate new kinds of technical data, as well as how anthropological approaches to the online and the offline can be augmented through computational methods.

What’s one thing people don’t know that you wish they did?

There is now frequent public discussion about the dangers of misinformation, whether related to politics or Covid-19. Misinformation is about more than information; it’s about identity. This means that talking about the quality of information isn’t enough. We need to know about how media and misinformation intersect with people’s social identities.

There is also a growing awareness of identity’s central role among political communication scholars and researchers studying the spread of misinformation. This signals things are moving in the right direction. To address these issues effectively, it will be important for broader audiences to understand what’s at play, how messaging can trigger certain affective responses, and how that plays into certain psychological processes that characterise how people respond to misinformation online and offline.

What kind of future do you hope to help design?

One of our stated aims is to advocate for the equitable availability of digital technologies. Uneven access to technology, which manifests in different forms of so-called “digital divide,” will become more entrenched in an increasingly technologised future. We advocate for a greater awareness of how socio-technical change intersects with both existing and future inequalities. And we envisage a space where socially-conscious research has a real, tangible impact, responsive to the needs of the people our research seeks to benefit.

Tell a story involving digital anthropology that really impacted you.

My masters thesis was based on 18 months of digital ethnographic fieldwork of a gay social network site. The site was designed around a public discussion forum. People filled out profiles and shared and commented on pics, public and private.

During my research, a new user named “Scaffolder” arrived. He quickly became a central focus of the network. His tragic backstory of self-discovery and coming-out woes triggered sympathetic responses from many users. People were eager to share their own stories of family and social rejection. Before too long, though, suspicious users revealed Scaffolder to be a “sock puppet” of another site user, causing a swift response of anger, and not a small amount of dismay, at how this popular member was revealed to be nothing more than a theatrical creation.

The strength of the response was quite striking. It revealed a great deal about how people invest personhood into their digitally mediated interlocutors, concretising them in their own image. But it also spoke to the acute risks involved in engaging with both known and unknown others in virtual environments.

This event reveals both the enduring importance of human relationships, and the mechanisms by which they are being fundamentally transformed through digital technologies. The lessons this story taught me were far reaching, especially in the context of the homophobic violence that is, to this day, enacted not only by groups and individuals, but by state actors through gay dating apps like Grindr.

In the intervening years, the focus of digital anthropology has shifted significantly as new interests and concerns emerged in relation to the development of new social and technological infrastructures. But this stands out as the moment when I grasped the stakes of people’s emotional involvement with virtual personhood, and the emotional hazards that digitally-mediated sociality entails.

What project are you proudest of so far?

I joined the team six months ago, so a lot of the work I’ve done has been focused on laying the groundwork for what comes next. Some work stands out. I’m currently leading a project exploring the impact of emerging technology-enabled markets on the capacity to experience social mobility, now and in the future. The project will go live this year.

With this project, we seek not only to make an active contribution to public understanding of the links emerging between technology and social mobility, but to start shaping the kinds of interventions that can broaden the benefits of these transformations to people who might otherwise be excluded.

Whose work makes you really jealous?

I could think of any number of amazing researchers whose work makes me step back and think “wow!”, but I’ll mention two. Sonia Livingstone is a professor of social psychology in the Department of Media and Communications at LSE, whose work on children’s rights in the digital age shows the impact that research can have beyond academia. It underlines what engaged research can achieve when it aligns key stakeholders, whilst giving a voice to people who otherwise may not be heard by powerful institutions.

Tom Boellstorff’s book, Coming of Age in Second Life, was life-changing for my development as a digital anthropologist. His work forcefully and convincingly demonstrates that the virtual world is worthy of anthropologists’ attention. Having the boldness to stand for ideas that go against the mainstream goes a long way in this field. This is a powerful motivator for how to value our work, though we still have much to do in terms of getting people on board.

What do you hope to work on in the year to come?

Apart from our work on social mobility, along with Nathalie, this year we will focus on creating frameworks for aligning computational techniques with approaches that are more often seen as the domain of anthropologists—including qualitative methods like interviews.

One of our biggest tasks is going to be deciding how to augment data-driven insights with other qualitative and quantitative techniques whilst helping BNP Paribas, our clients, and the broader public understand the ethical challenges of building knowledge architectures around internet-mediated data, especially in an industry environment.

More generally, I’m excited about getting a chance to write about digital anthropology for a new audience and to create a new space for digital anthropological research at L’Atelier.

To learn more about digital anthropology, at L'Atelier or otherwise, check out Nathalie Béchet's QA.

17 Jun 2021

-

Angela Natividad

Illustrations by Frankie Huang.

DATA-DRIVEN TECH & SOCIAL TRENDS. DISCOVERED WEEKLY. DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX.

02/03

Related Insights

03/03

L’Atelier is a data intelligence company based in Paris.

We use advanced machine learning and generative AI to identify emerging technologies and analyse their impact on countries, companies, and capital.