The double-edged dissident darknet

For darknet users in Russia, the close of 2021 brought anguish after a year of combat over internet freedoms, expanded internet legislation, and new regulations for tech companies.

On December 8, Russian authorities blocked access to the Tor website domain, a primary darknet gateway, where the Russian Federation accounted for over 45 percent of mean daily bridge users, especially following the Feb. 24 invasion of Ukraine. The block is a feat the Russian Interior Ministry has longed to achieve since 2014, when it offered hackers 3,9 million roubles to crack Tor users’ identities.

These incidents are emblematic of the longstanding global tug-of-war over internet privacy embroiling governments, civil society, and tech companies.

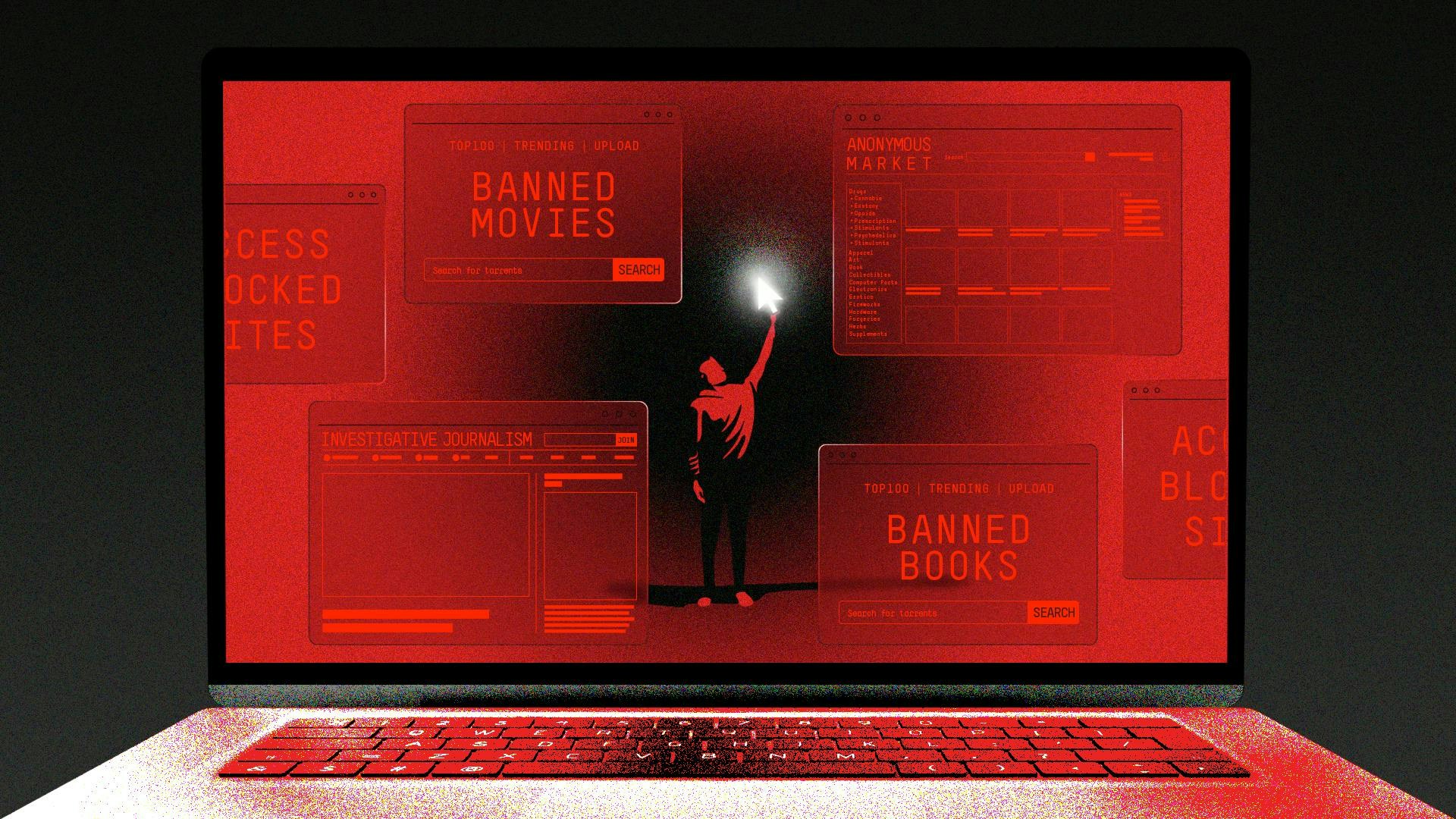

Popular media narratives position the darknet as a shadow-space, where leery people exchange child pornography, or peddle drugs and weapons on websites that resemble eBay. But it is also a safe haven for journalists, researchers, political dissidents, and citizens seeking privacy … making Tor an accidental seismograph for measuring democratic corrosion.

The terms “darknet” and “dark web” are widely contested; technical experts refer to them as “anonymity networks.” Open-sourced and publicly funded, The Tor Project—a US 501(c)(3) research nonprofit—goes by the mantra, “Defend yourself against tracking and surveillance. Circumvent censorship.” It is sometimes hailed as a pro-democracy tool for dissidents in repressive governments. But recent research reveals that countries considered “liberal” also abuse government surveillance and personal data technology at higher rates.

Perhaps this is no surprise.

Globally, we’ve witnessed a rise in illiberal democracies (known as “democratic regimes”): Systems where elections take place, but citizens are nonetheless kept from acquiring certain types of knowledge, while also facing reduced civil liberties, like gradations of privacy and freedom of expression.

According to the 2020 Democracy Report by V-Dem Instituite, one-third of the world’s population now faces dramatic rises in autocratic government behaviour, especially in European countries. Its 2021 report found significant evidence of media freedom restrictions, with two-thirds of 144 countries tracked imposing moderate or major restrictions, and 32 countries substantially declining in freedom of expression and media. Because of data surveillance by Big Tech and voter suppression, particularly gerrymandering, in recent elections, the United States, for example, has exhibited such decline.

It seems the world has entered a period of democratic backsliding—a gradual decay of traits democracy is supposed to espouse, particularly privacy.

The shifting sands of privacy

Privacy is not only a darknet value; it is critical to healthy democracy, ensuring the protection of personal freedoms, information, and autonomy in society. To understand how the darknet functions as a metric for democracy, however, it’s helpful to understand the three technology-driven paradigm shifts that inform what we assume privacy to be. These shifts resulted in reforms through policy (legalities) and design (facilitated by technology), which inform the darknet today.

In the nineteenth century, privacy was legally enshrined in policy for the first time. John Stuart Mill, the father of classical liberalism, opened his 1865 essay “On Liberty” by asserting that tyrannous potential of governments must be counterbalanced through citizen liberties.

In Mill’s time, emerging technologies yielded radical communications inventions. The postcard, and early telephone services with party lines, created new privacy concerns, since such messages and discussions can be openly read and heard. Mirroring contemporary internet exposure conundrums, the innovation of flash photography filled newspaper gossip columns with unauthorised images, exposing the private deeds of laypersons and wealthy community members alike—the first “democratised” privacy invasions. (Prior to this, privacy was tacitly understood as a privilege of the affluent.)

Responding to these issues in a Harvard Law Review article called “The Right to Privacy,” US Supreme Court justices Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis declared privacy inherent in common law. This yielded torts that are now part of the First (referring to media) and Fourth (referring to government) Constitutional Amendments.

That was 1890. Let’s jump a century ahead.

In the late 1980s, the Cypherpunk movement initiated privacy by design in software, cryptography and frameworks for anonymity-granting technologies. Its 1992 mailing list discussed online government monitoring and corporate control of information. Published in 1993, A Cypherpunk’s Manifesto proclaims, "Privacy is necessary for an open society in the electronic age [...] We cannot expect governments, corporations, or other large, faceless organisations to grant us privacy [...] it must be part of a social contract.”

Less than a decade later, their principles were tested by the rise in mass electronic surveillance after 9/11, sparking global debates about unprecedented government interference into civil liberties, even when justified for national security. The USA Patriot Act and FISA Amendments Act of 2008 (PRISM surveillance program) shielded private companies from legal action when cooperating with US government agencies in intelligence gathering. Until Edward Snowden revealed PRISM’s extensive details to a team of journalists in 2013, the populace remained unaware of the terrifying breadth of global internet data interception (emails, photos, chats, and videos) via direct access to the servers of big tech companies and wiretapped calls.

The third shift happened in March 2018, when data-mining firm Cambridge Analytica obtained access to over 50 million Facebook user profiles to retrieve users’ behavioural data, which helped target voters for Donald Trump’s presidential campaign. This underlined Big Tech’s capacity to manipulate democratic processes and highlighted a correlation between the scaling of tech and privacy loss. Users and policymakers questioned the powers of companies that exchange free services for advertising data, and began turning to shielding technologies.

How Tor ‘vets’ democracies

Tor, short for “The Onion Router” (and German for “gate”), was created by the US Naval Research Laboratory. It operates via a decentralised bank of volunteer computers worldwide.

This decentralised structure resembles the design of cryptocurrencies, and global citizen-based movements: It eliminates the potential for single points of failure to cascade, and abuse by sole presiding authorities. The Tor Project is funded by a mix of interests, from private foundations and corporate sources, to government agencies. Its 2020 IRS filing brief documents contributions from the US Department of State, DARPA, Radio Free Asia/Open Technology Fund, Media Democracy Fund, Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA), Digital Impact Alliance—United Nations, and Mozilla. Over 2,5 million users worldwide use its service.

“Part of Tor's power is that its fate is not in the hands of one company, or a handful of people, or centralised in any one geographic location,” said a Tor representative. “Thousands of people and organisations invest in Tor, help improve our code, run our network, fight when censorship takes place, and make Tor as powerful as it can be.”

Typically, when someone connects to a website, they leave breadcrumbs of personal information that can be tracked by governments and a panoply of companies: The website operator, analytics tools, third-party services, and advertising data miners. Alternatively, Tor encases user traffic in multiple layers of encryption, then sends it through a worldwide network of three random nodes (servers) called relays. The last “exit relay” then sends the user to the website they seek.

This system “scatters” the breadcrumbs. Internet service providers can't track specific users’ activity, because they see a Tor network connection instead of an IP address, making it difficult to "fingerprint" people by browser configuration or by collect browsing history. In recent years, however, ISPs and some governments—notably China, Iran, and Russia—began blocking Tor relays. "Pluggable transport" and “Bridge” relay options that are not publicly listed can circumvent the blocks.

Partly for this reason, Tor’s data can measure certain political pulses. A 2016 research paper by political scientist Eric Jardine used Tor usage metrics (2011-2013) to measure political repression in 157 countries, based on an aggregate index of Freedom House’s political rights and civil liberties measures, as well as other variables. It found that countries where Tor is most used are either highly repressive or highly liberal.

It’s how Tor is used that differs on either side of that extreme. Despite the polarising darknet narratives that made Tor infamous, just ~6,7 percent of users visit for illicit purposes, with higher concentrations of illicit activity in “free” countries—which host most of the network’s infrastructure. Predominantly, global Tor use revolves around searching clear or “free” web content; users from “illiberal” or “repressive” countries mostly use it for this purpose. A follow-up paper from 2020 reported Tor is more prone to abuse in countries commonly considered “free” by western standards.

“Browsing the surface web using Tor is unpleasant,” says sociologist Andrew Lindner, who co-authored the 2020 paper. “Those in free nations would not have much incentive to use it for that purpose unless for internet privacy concerns. In high volume Tor use countries with more restricted societies like Russia and China, a majority of users access the surface web with pro democracy content a likely motive.”

Anecdotal evidence suggests it’s also used as a shield from personal data collection or government surveillance. Tor use for these purposes may be rising among users in democratic nations.

Chilling effects and decentralised movements

Since online anonymity can beget moral hazards, trust is a major factor in privacy-rich environments. Cryptocurrency, the darknet’s cousin in anonymity, exploits the Byzantine Generals Problem, a game theory dilemma describing challenges faced by decentralised parties to arrive at a consensus in the absence of a trusted central party. In a network where no one can verify others’ identities, how can members collectively agree on a certain truth? Bitcoin solves this problem with cryptographic security and public-key encryption.

Dr. Julia Norgaard, assistant professor of economics at Pepperdine University, sees trust as essential social capital for darknet engagement. In her 2020 TEDx Pepperdine talk, she cites how merchants build trust selling unregulated illicit goods, using ratings, forums, and platform dispute resolution. Similar principles of trust apply to global citizen movements lacking centralised leadership, where anonymity is a lifeline.

The Center for Applied Nonviolent Actions and Strategies (CANVAS), founded by originators of Serbia’s 1999 OTPOR movement (which helped topple President Slobodan Milošević’s regime via nonviolent mobilisation tactics), advocates for nonviolent resistance through a network of consultants and publications. Its landmark guide emphasises decentralised leadership, since capturing or punishing a collective mass of anonymous citizens is difficult.

CANVAS’ approach proved justified when documents, obtained by The Guardian in 2017, revealed undercover NYPD officers posing as protestors. They filmed and infiltrated small groups of Black Lives Matter activists, gaining access to text messages to “wither away” protests by identifying leaders. In 2020, The New York Times reported a rise in downloads of Signal, an encrypted messaging platform, among Black Lives Matter protestors hoping to circumvent law enforcement surveillance.

This accompanied an increase in Tor use dating back to 2015, after extensive reports of police spying and attempts to infiltrate them. Experts likened these government actions to the corrosion of the Black Panther Party in the late 1960s, when the FBI unleashed a covert surveillance operation targeting civil rights groups and leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr. The CIA also recruited African-Americans in this period to spy on party members.

Free speech, and the ability to peacefully demonstrate, are central to democracy. In societies where governments control traditional media, the internet can be a lifeline. Prior to its emergence, dissidents and activists disseminated information through cassettes, flyers, fax machines, and phone messages. But in the last two decades, the internet has been continuously besieged by mass shutdowns, censorship of social media, surveillance, and penal action threats, producing “chilling effects” where the populace refrains from free expression for fear of retribution.

From 2010-2012, revolutions spread across the Middle East and North Africa, driven by social media: The Arab Spring. The darknet and Tor became a safe place for organisers to share information without government scrutiny, including remedies for tear gas, and protest organisation information.

In Egypt, Libya, and Syria, website blockages and internet shutdowns by officials sought to quash protests. Tunisia’s government hacked into and stole passwords from Facebook accounts. Iran’s regime also routinely blocked sites and deliberately reduced internet bandwidth, with heightened activity after the 2009 Green Revolution.

The trend continues from the Syrian revolution to the present: In 2020, Facebook employee Behdad Esfahbod was arrested and detained in Iran’s infamous Evin Prison for alleged friendships with activists, who were developing censorship circumvention tools.

National security concerns usually justify surveillance and online censorship. As far back as 2006, the OpenNet Initiative, a former research project examining censorship and surveillance, uncovered internet filters that block sites and pages containing keywords related to forbidden subjects in 25 of the 46 nations tested, including China, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Vietnam.

In 2015, FBI Director James Comey called for "back doors" on encrypted services, observing that the Islamic State uses social media and dark web sites for recruitment.

While CANVAS recognises the internet as an essential tool, social media has, like the darknet, been double-edged: platforms like Facebook and Twitter were initially considered democracy-enabling … until federal agencies and regimes began tracking and arresting protest participants via IP addresses, geotagging, and facial recognition technology—piggybacking from tools commonly employed by online advertisers.

In 2018, The Tor Project began officially soliciting usage stories for civic movements. One of the first documented censorship circumvention cases involving Tor occurred in 2005, when an Arabic usage guide was distributed in Mauritania in response to filters blocking sites containing keywords related to forbidden subjects. As a result, the government stopped filtering.

Government hostility towards anonymity-granting technologies has increased in the last decade. The People’s Republic of China censors Google, Wikipedia, YouTube, and other technologies that provide identity-shielding affordances, and regularly surveills dissidents. A 2012 paper examined how the “Great Firewall of China” blocked Tor, and offered countermeasures—prevailing in 2022. On June 30, 2020, the Hong Kong national security law came into effect, giving the government censorship power over anti-government or politically sensitive websites appearing to “endanger national security.”

“I worry now about the vulnerability of Tor more than when I started my research,” said Lindner. “Tor is similar to the internet itself: a great example of US infrastructure spend. Many technologies are developed with one set of ideas in mind, leaving room for unknowns to occur. I don’t think anyone developing software can anticipate all these vulnerabilities where consequences can result from one flaw.”

Sound familiar?

The everyday darknet

Could Tor represent a next wave in user privacy protection? In 2014, Facebook released a Tor connection link, availing access to millions of global users in countries that block the platform. In 2021, it was updated to an onion version 3 address. In March 2021 Twitter released a .onion version to bypass Russian blocks. Apple released the iCloud Private Relay in beta with its 2021 iOS 15 software upgrade. It reroutes Safari browsing activity through Tor-like relays.

Since much of Tor’s infrastructure is clustered disproportionately in “free” countries, jurisdictional control can be exerted. It may well be rendered “privacy-obsolete” after more online attacks, like Russia’s in 2021. Which begs the question: is online privacy the solution to growing democratic backsliding, or merely a circumvention tool? Instead of continuing to play cat-and-mouse with solutions like Tor, why not directly confront the ills contributing to the decline?

The story of darknet use is often also recounted as a one-sided narrative, that of a democratic west furnishing needful technology to people living in more formal governmental regimes. Yet users in liberal countries increasingly turn to Tor for similar reasons, not to mention disproportionately using it for illicit purposes. The reality of Tor usage data undercuts overly simple narratives that sustain western imperialism.

Perhaps just as importantly, what are Tor’s own ambitions for growth, if any?

“There’s a lot we don’t know,” says Lindner. “No one can see the entire Tor chessboard and this is by design. There are enough signs to see both the benefits of Tor and also be troubled by it and wanting to ask questions. We need to exercise caution with claims anyone makes.”

12 Jul 2022

-

Jessica Buchleitner

Illustration by Debarpan Das.

02/03

Related Insights

03/03

L’Atelier is a data intelligence company based in Paris.

We use advanced machine learning and generative AI to identify emerging technologies and analyse their impact on countries, companies, and capital.