Meet the More Digital, and More Diverse, Dungeons & Dragons

Last summer, as government after government closed public life—then their borders—like cascading dominoes, Eric St. Pierre realised he’d need to find a new job.

He’d always loved Dungeons and Dragons (D&D), the collaborative storytelling game. Once the province of nerds in basements, D&D is now—thanks to streaming, a new and easier-to-understand set of rules, and online play platforms—a digital phenomenon.

In D&D, players create characters—sorcerers, thieves, bards—and embark on a shared choose-your-own-adventure. One person, the Dungeon Master (DM) or game master, guides the narrative as it unfolds, describing the topography players traverse, and dreaming up creative challenges for them to encounter.

The game’s official publisher, Wizards of the Coast, a division of Hasbro, regularly releases new scripts for these adventures. Some DMs, as well as thousands of independent writers and creators, create their own.

When co-creators Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson published the first D&D rulebooks in 1974, they promote the game as cheap and easy. “It is relatively simple to set up a fantasy campaign, and better still, it will cost almost nothing,” Gygax wrote.

But, spurred in part by digital changes to how we gather and game, D&D has changed beyond what Gygax and Arneson perhaps first envisioned. Today it is an expanding and lucrative global pastime: An official Wizards press release described 2019 as D&D’s “best year ever,” estimating the game had 40 million fans worldwide, including a long list of celebrity enthusiasts. Many fans come from regions beyond its historical US stronghold.

“We’re seeing our playerbase increase strongly in Europe and other regions as well, and that’s very much in our thoughts as we make future plans,” Wizards said in a written statement.

When the pandemic struck, many gamers folded up their in-person gaming tables, but that doesn’t mean they stopped playing. Instead, they flocked to specialised online platforms that let distanced friends recreate the experience of in-person play. Many offer features—maps, voice chat, real-time dice rolling—specifically intended to ease a role player’s isolation, and that speak to an emerging change in the D&D landscape. More often now, players discover and learn the game online, opening new opportunities for fans, companies and creators, while challenging assumptions about who plays D&D and how.

“D&D reached new heights in the early stages of the pandemic, as people were looking for games to play at home and ways of staying connected with their friends during times of social distancing,” said Wizards in a written statement. “As players adapted to playing remotely, there was enormous growth in the usage of tools that facilitate online D&D play.”

Roll20, among the most famous of these online tools, was Kickstarted in 2012 on the promise that it would focus on “storytelling and camaraderie rather than gameplay mechanics.”

An August 2020 post on the Roll20 blog noted that the platform saw “unprecedented growth across nearly every game system” over the most recent quarter, with many people “staying connected during this time by playing games together.”

The Rise of the Pro DM

Seeking inspiration for his new career, Eric browsed platforms like Tabletop Wizard, which lists more than 37.000 people looking for games. He realised what an enormous demand there is for the game, and how digital tools might help him meet it. Thus his fledgling career as a digital DM was born.

Some DMs charge for games, but it’s rarely a full-time gig, and it’s often in person. In a 2019 Bloomberg article, writer Mary Pilon profiled a pro DM who mixed potions and marked maps in his kitchen. She described the job as “the perfect side hustle.”

But what about people making it a main hustle? The first time Eric listed a paid game on Roll20, in mid-2020, nobody bit. Realising he'd need to step up his marketing, he trimmed his beard, put on makeup, and took a professional profile photo. He updated his Roll20 profile copy with specifics about his decades of experience, and set his price at $10/seat for a 4-hour session.

Within 15 minutes, it sold out. He ran two campaigns a week for two months, then raised his prices to $20/session and upped it to 4 campaigns a week.

That money is reinvested in the experience. Eric has taken improv and voice acting lessons to create different accents and voices for the various characters players encounter while journeying. He wrote backstories for 135 non-player characters, all of whom interact in an elaborate linked world.

Like his characters, his players come from everywhere: Alabama to Alaska, Dubai to Sweden. They work on Wall Street and at Walmart. And though a few groups knew each other beforehand, in a reversal of the days when a game required a friend group to play together, most people who find themselves at Eric's tables are “signing up for the games themselves.”

The appeal of these games, Eric says, is how they touch on universal ideas of right and wrong, heroism and villainy. “What are the primal fears of human culture?” he asks. He helps players craft characters and storylines that speak to their own out-of-game anxieties. For example, one player he described is using the game to curb his impulsiveness.

In 2021, Eric upped his campaigns to 5 to 6 per week—“a pretty nice level of income” in his part of Texas, he remarks.

Over the past few months, several aspiring DMs have sought him out for advice, many finding him via online forums like reddit.

“A lot of people are trying it and not being successful,” he says. “People get this in their head that they’re going to succeed because GMing is easy. No—GMing is a lot of emotional investment.” (Eric prefers the term “Game Master” to “Dungeon Master because of the “potential negative connotation related to dungeons”, and because he runs other games besides D&D.)

While it isn’t easy, Eric sees enormous demand for good, professional DMs, as well as for services that offer “matchmaking” for players and DMs. He envisions DMing as a job he can do for decades: Not long ago, he got a 10-year business license. His professional outlook reflects both the possibilities of the digital future and the precariousness of growing old in the United States: “You gotta have something you can do as an income because Social Security is not going to cover everything. I can talk to people even when I’m 70.”

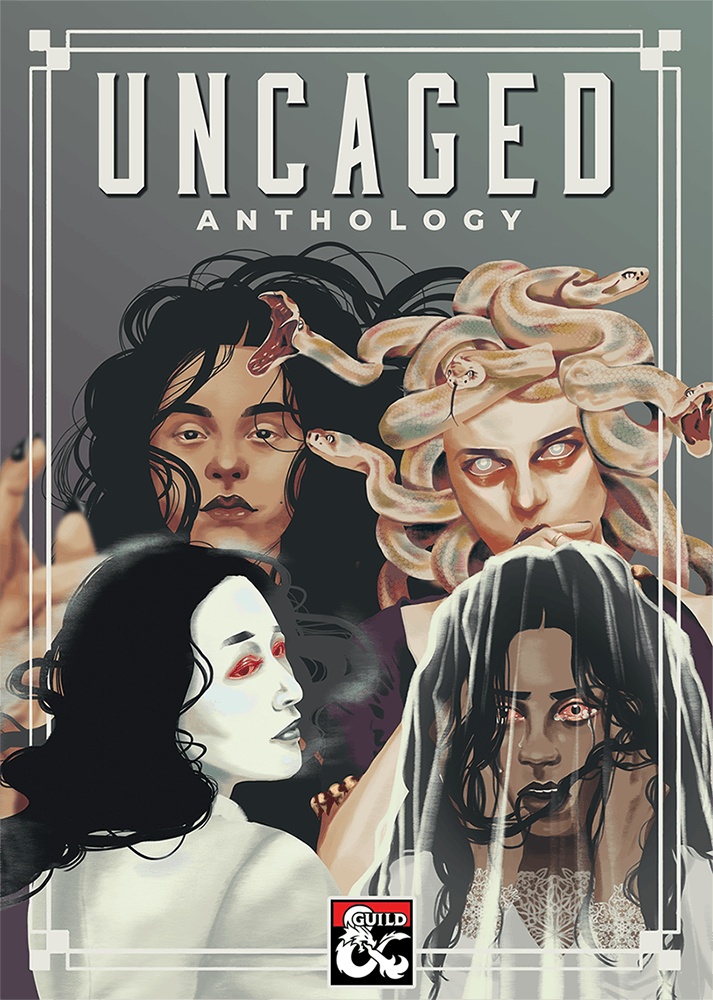

Cover of the bundled version of the Uncaged anthology series, featuring Medusa (vol. 1), Rusalka (vol. 2), Yuki-Onna (vol. 3) and La Llorona (vol. 4). Illustrations by Samantha Darcy.

Diversity finds D&D

The game’s fanbase isn’t just bigger than before; it’s more diverse. For many fans, D&D isn’t just a game, but a way to reflect on society. One such fan is Ashley Warren, editor of the Uncaged anthology.

Ashley loved fantasy as a kid, but didn’t play D&D until she was an adult. While paging through the official guide to D&D monsters, she noticed how many female monsters were harpies, medusas, hags—“creepy old women,” she laments.

Medusa, in particular, appealed to her. In legend, Medusa was a priestess raped by Poseidon, transformed into a snake-headed creature by Athena, eventually beheaded by the hero Perseus. A survivor of sexual violence, Medusa often appears as a villain in stories, a characterisation that D&D’s official material does nothing to challenge (its official manual lists four versions of a Medusa, all evil.)

Who’s a hero, and who’s a villain? Who gets to decide? Ashley put out a Tweet asking whether people would be interested in D&D adventures that put so-called monsters at the centre of their own stories. She was inundated with enthusiastic reptiles from artists and writers.

In the hit movie "Pirates of the Caribbean," the pirate captain Barbossa famously says, “The Pirate’s Code is more what you’d call guidelines, than actual rules.” The same could be said of D&D’s official source material. Players and DMs were always encouraged—in fact, often required—to write their own stories to supplement official offerings. Under Wizards of the Coast’s Open Game License, independent creators can sell these materials legally.

In 2016, perhaps to capitalise on the rising popularity and reach of these independent offerings, Wizards teamed up with OneBookshelf—a linked group of sites for community-created gaming content—to launch the DMs Guild. In exchange for the right to use a wider set of Wizards’ intellectual property, authors give a 20 percent cut of their sales to Wizards, and another 30 percent to OneBookshelf. Most offerings are priced between $2 and $20.

In just four years, DMs Guild became a vibrant marketplace, a one-stop shop for many DMs. According to Lysa Penrose, brand manager for DMs Guild, 5-10 new adventures are added daily, making it “a very active platform.” (For Wizards, the platform is also a way to scout new writing talent, and many have “gone on to work with on official D&D products,” the company stated.)

Ashley’s first volume of Uncaged was published on DMs Guild in June 2019. It quickly sold more than 5.000 copies, a sales milestone that fewer than half of a percent of the site’s titles have reached. In Uncaged’s pages, fans find adventures that retell the stories of hags, banshees, sphinxes, and—of course—Medusa.

Uncaged also became a gathering place for independent writers and creators. New projects were born on the sidelines. Some of these offshoots called themselves “the ‘Un’ projects,” says Caroline Amaba, a developer and designer who answered the call.

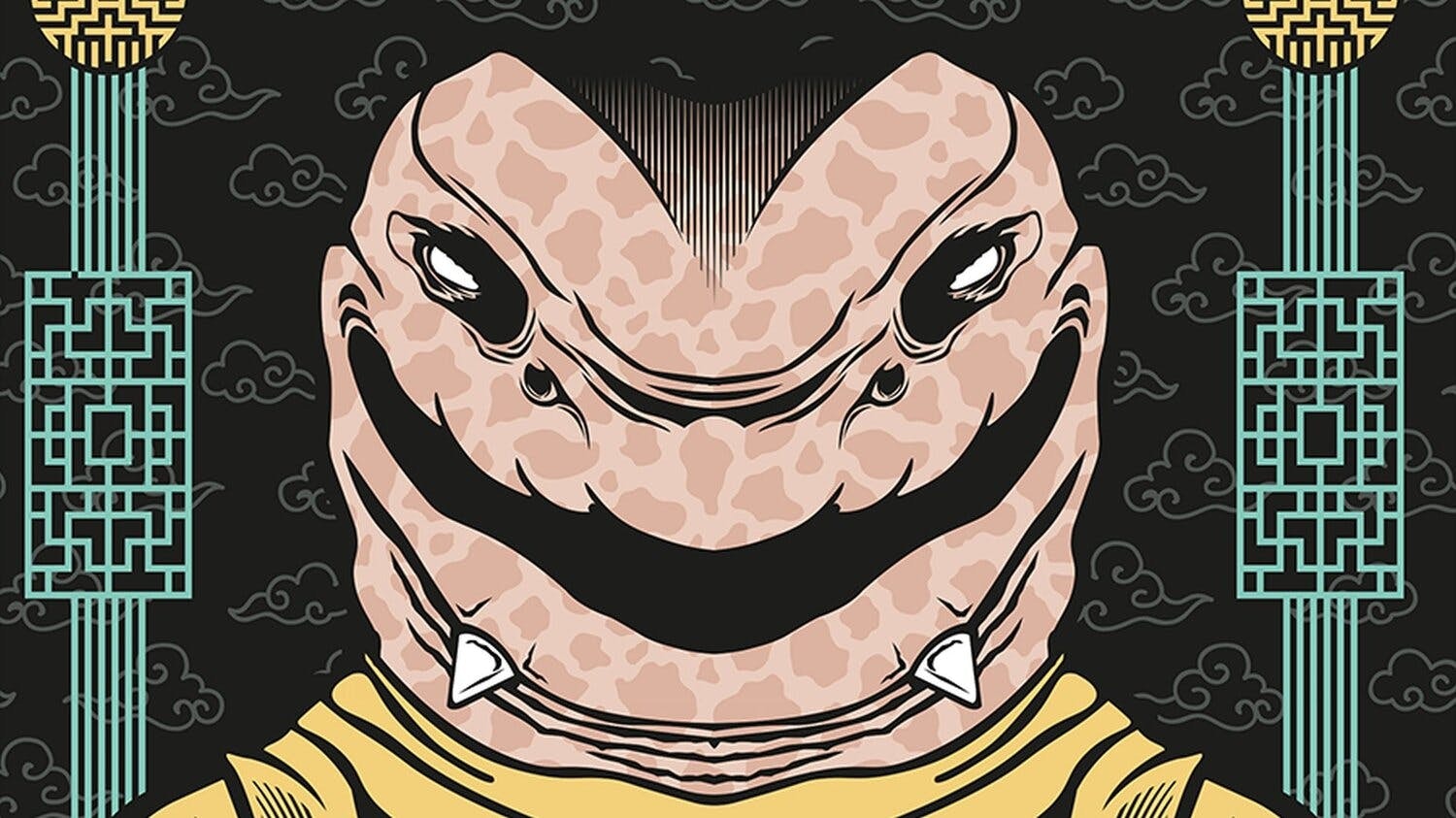

In a Discord chat for Uncaged fans and writers, Caroline met Jacky Leung, who, inspired by Uncaged, launched Unbreakable, a series of new adventures in Asian settings.

At that point, D&D’s primary attempt to represent Asians was the continent of Kara-Tur, whose mythology—like the menu at a generic pan-Asian restaurant in the American suburbs—was loosely based on several Asian cultures. The official adventure book, Oriental Adventures for D&D Third Edition, was written in 2001. Jacky found both efforts severely lacking.

“Kara-Tur has a lot of problems and aspects that need to be redone,” he says. Instead of waiting on official change, Jacky, Caroline and their co-creator Jazz Eisinger took matters into their own hands, opting to create adventures that reflected the mythologies and experiences of Asian players, written by and for them. What he initially envisioned as a one-off adventure swiftly snowballed into an “Own Voices” series.

Shareef Jackson, a STEM educator and cast member on the Wizards of the Coast-sponsored D&D podcast Rivals of Waterdeep, praised the book as an essential resource for those who want to play Asian characters but avoid terms like “exotic” and “Oriental,” which pepper past official texts. “If you want to build characters with Asian backgrounds, this is how you do it right.”

In March, Jacky was furloughed because of the pandemic. In August, he switched to writing and editing game content full-time.

“It was a difficult choice because I never planned it this way,” he says. “Times are weird.” His main income is royalties from work published through DMs Guild and elsewhere.

No matter how you slice it, writing independent adventures for D&D is not a fast way to get rich. Jacky, Caroline and Jazz have an elaborate table to determine who gets royalties from Unbreakable. Royalties are divided into shares, and distributed based upon how much work people did: the smallest amount is a quarter share. They list Unbreakable on a related site, rather than DMs Guild, to keep the 20 percent of sales that would otherwise go to Wizards of the Coast.

“A lot of us have some kind of beef with Wizards,” says Caroline. Jacky elaborates: despite calls from Asian creators and players, Wizards still offers Oriental Adventures. (The listing does have a disclaimer: “Some older content may reflect ethnic, racial, and gender prejudice that were commonplace in American society at that time. These depictions were wrong then and are wrong today.”)

Caroline has no plans to leave her day job as a software engineer, but says Unbreakable offers an outlet for her pent-up creativity, and provides access to a community she didn’t know was there. “Uncaged spurred this mini-renaissance between the indie RPG community.”

Cover art by Joshua Mendenhall for Unbreakable volume 1.

What's race got to do with it?

In mid-2020, independent creators received even greater visibility. Racial equity protests in the US shined a harsh spotlight on generations of injustice, including in D&D.

When players create a D&D character, one of the first choices they make is the character’s “race.” Options include dwarves, humans, elves and orcs. Each has “Racial Traits,” such as increased charisma or dexterity, echoing Western fantasy stereotypes—elves are graceful and dexterous, while dwarves are cunning and hardy. These racial bonuses affect gameplay: A more dexterous character will be better at certain tasks.

The idea of racial determination sits poorly with an increasingly diverse player base.

“The traits tied to race need to go,” says Shareef. “You can keep traits, but they should be aligned to the experience of the characters.”

For Shareef, correcting racial stereotypes within the game is linked with correcting stereotypes outside it. The Rivals of Waterdeep podcast, sponsored by Wizards of the Coast, features a diverse cast in a space where well-known streamers—like the cast of mega-hit D&D podcast Critical Role—are white, or at the very least, limited in diversity. He’d love for D&D to be a bigger part of his professional life, but says there’s a “glass ceiling,” shaped in part by fan perception.

“When it comes to being able to make a living off of just D&D, there still is an expectation that you look and act a certain way,” he says. Thus, many diverse projects risk getting put into an “other D&D” category, he says.

But that might be changing.

In August 2020, philosophy professor and gamer Eugene Marshall released an independent book that did what Shareef asked—allow players to decouple race and ability entirely. Eugene called it Ancestry & Culture—An Alternative to Race in 5E.

Ancestry & Culture replaces Racial Traits with bonuses that come from ancestry—some version of genetics and heritage—and culture, the environment and society in which a character is raised.

In February 2020, he put the book on Kickstarter, seeking $300 to commission art for the cover. He raised over $7000. The book became a phenomenon, selling thousands of copies on DMs Guild and earning accolades. Charlie Hall, who covers tabletop roleplaying for gaming site Polygon, wrote that the book “could serve as the way forward for the entire gaming industry,” suggesting how wide-reaching this particular challenge is, and how eager people are to find a solution.

It’s not just indie creators changing the rules; Wizards has taken note, too. In 2020, it released a new rule book that gave players even more options for customising characters’ origins. In January 2021, Wizards went further still, releasing early playtesting materials that suggest future D&D books will follow Eugene’s lead. These updated official rules will separate a character’s language, alignment and abilities from race, giving players a choice when it comes to qualities that are “purely cultural.”

Such changes are welcome for Manila-based Pam Punzalan, who served as a sensitivity reader on Ancestry & Culture. Sensitivity reading is a better-known practice among indie publishers, but it’s crossing into official use. In a June 2020 blog post about race in the game, Wizards of the Coast said it is “incorporating sensitivity readers into our creative process.”

When Eugene emailed, Pam had never worked as a sensitivity reader before. It was a “shot in the dark,” she says. Friends told her it was “critically analysing a text” to figure out “whether these ideas are harmful or discursively sound or what,” something Pam knew how to do.

When the pandemic struck, she scaled down her real estate work to focus on narrative design and sensitivity reading full-time, in response to demand from clients outside the Philippines. The exchange rate works in her favour. “I can get what I like and still pay the bills,” she says.

Perhaps because she works across cultural and geographic boundaries so often, she has a wide perspective of what D&D is today. It would be a mistake, she cautions, to see the fandom as a single monocultural “family.” Pam is part of an expanding network of Twitch and Discord channels for Southeast Asian gamers and creators, where she sees enormous frustration, as well as love for D&D.

“You have creators who have lost faith in Wizards of the Coast because they feel ignored or underrepresented … and then you have the other side of gamers, players and community organisers who feel there’s a lot of emotional resonance that D&D can provide because it was the gateway drug for a lot of us,” she says. These two sides are not mutually exclusive.

Projects like Ancestry & Culture boosted Pam’s profile. Many of the most successful projects in today’s gaming scene got an early boost on Kickstarter: The Critical Role team used it to raise money for an animated series, while Roll20 and Ancestry & Culture secured key initial funding. But creating a Kickstarter project is only available to people in a handful of countries, many in North America and Europe. In addition to living in the right jurisdiction, project creators must have a bank account, an address, and a government-issued ID to create projects and receive funds.

These requirements—which depend on things like local tax and banking laws, as well as global interest—divide creators but also encourage global collaborations.

“Kickstarters have a very hallowed position for a Southeast Asian designer, mainly because we have no access to Kickstarter, so there’s no way for a personal designer to go on their own steam and create a project where they have full control,” Pam says.

The creators of Unbreakable, too, have global payment limitations and possibilities on their minds. They talk of one day creating a publishing entity around their series, accessible to people regardless of banking regulations or country. They point to platforms like itch.io, an indie game marketplace that has become a popular site for RPG and video game creators outside of the United States and Europe. While D&D may have served as a gateway to the game, fans and players’ creativity and connection now go far beyond one game’s borders.

“We want to provide that platform, help supply to a broader global market, and cater to our Asian fanbase. That’s who we’re here for,” Caroline says.

In a time when the pandemic has changed how so many connect with people, she perhaps cuts to the heart of storytelling’s original purpose when she says, “We’re telling these stories for each other.”

14 May 2021

-

Anika Gupta

DATA-DRIVEN TECH & SOCIAL TRENDS. DISCOVERED WEEKLY. DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX.

02/03

Related Insights

03/03

L’Atelier is a data intelligence company based in Paris.

We use advanced machine learning and generative AI to identify emerging technologies and analyse their impact on countries, companies, and capital.