Filters Empower Lolita Syndrome... But It's Not (Quite) Tech's Fault

In 2015, Snapchat released beautification filters. It seemed like a benign way to enhance your look for public consumption, or creatively address "every beauty complaint."

If you aren't familiar with these filters on Snapchat, perhaps you encountered them on Instagram, where they appeared in 2017.

Since, writers and vloggers have highlighted the risks they pose to mental health. A 2017 study found that 55 percent of plastic surgeons reported clients wanting "to improve their appearance in selfies," up from 42 percent three years earlier. Typing "snapchat dysmorphia" into YouTube yields features from CNBC, TODAY, Global News, Fox News, and the Boston University School of Medicine, all released within the last two years. The term describes "an unrealistic expectation of one's image brought on by social media." It extends from body dysmorphia, a mental health condition that, per the most recent edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), references an inability to “stop thinking about one or more perceived defects or flaws" that appear minor to others.

In late 2019, Instagram banned user-made cosmetic surgery filters, after granting users the ability to create and share their own filters just months earlier. But the trend exists outside of filters, too; filters merely provide a shorthand for apparently highly desirable features. In her New Yorker piece, “The Age of the Instagram Face,” Jia Tolentino elaborates:

It’s a young face, of course, with poreless skin and plump, high cheekbones. It has catlike eyes and long, cartoonish lashes; it has a small, neat nose and full, lush lips. It looks at you coyly but blankly, as if its owner has taken half a Klonopin and is considering asking you for a private-jet ride to Coachella. The face is distinctly white but ambiguously ethnic—it suggests a National Geographic composite illustrating what Americans will look like in 2050, if every American of the future were to be a direct descendant of Kim Kardashian West, Bella Hadid, Emily Ratajkowski, and Kendall Jenner (who looks exactly like Emily Ratajkowski).

Inspired by that article, YouTube vlogger and social commentator Khadija Mbowe reflected on the phenomenon in a video titled, “Why do all these influencers have the same face?” It has been viewed nearly 700.000 times.

Why do these filters exist? What vacuum do they fill, and what do they say about technology and its implications for the lived human experience?

Who's the fairest of them all?

Infantilised beauty: Here's to Bratz dolls

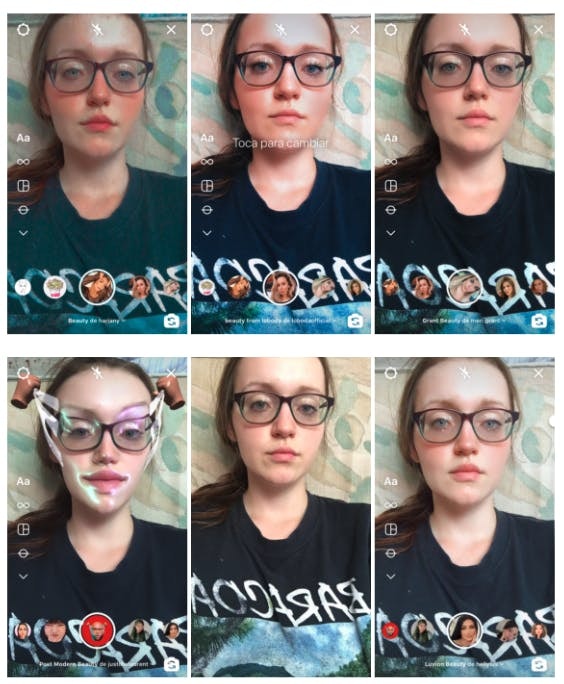

Can you find the original photo of me?

An example of six filters the author has tried on herself, including redder lips and cheeks, paler skin and even a filter that appears to plastify and lift her features.

As the filters bend, pull, plump, and taper my face, I am reminded of Bratz dolls, what felt like an exotic childhood alternative to Barbie. As a 12-year-old, I related to their plump baby faces, their different colours and characteristics, which Barbie seemed to whitewash and adultify. If Barbie was my mother's generation's beauty standard, Bratz were mine.

Retrospectively, I understand why I found them exciting. They tugged at a sexy-cute dichotomy that has influenced female beauty standards for millennia, encouraging women to be desirable while remaining childlike. Bratz embody the infantilisation of beauty ... and to understand Snapchat filters, it is critical to understand this idea first.

"Infantilisation of beauty refers to the way that attractiveness for adult women is associated with looking girlish," says Dr. Gwen Sharp, Assistant Professor of Sociology at Nevada State College. "[They display] a non-threatening coyness. On the flip side, we sexualise young girls and teens, presenting them as alluring Lolitas who aren't as innocent as they seem, despite their schoolgirl uniforms."

"Lolita" refers to author Vladimir Nabokov's 1955 title character, a 12-year-old girl who becomes a middle-aged man’s obsession. After marrying her mother, he makes Lolitaa his mistress.

Students in the United States often read this book in high school, under the pretext that it illustrates the trope of the “unreliable narrator.” Lolita—systematically listed among the top works of the 20th century—has been made into films, operas, ballets, and a (controversial) musical. The name adorns a retailer in Uruguay. It has even marked the English language: Merriam-Webster defines "Lolita" as "a precociously seductive girl."

Infantilised beauty, and the warm cultural recognition of what is essentially the pathological fetishising of children—not to mention the latent victim-blaming in the definition above—is an old cultural inheritance. Without serious investigation of why it exists in the hivemind, technological innovations in beauty will only facilitate the distortion of women and perpetuate this ideal.

People have modified their appearances for thousands of years. Makeup is an ancient, relatively benign beautifying tool, notes Dr. Sharp. It allows users to lend the impression of plumper lips or a flush in the cheeks, for example. Today it is often coupled with laser technology, cosmetic surgery, and extreme dieting or exercise. All these physical modification options, compounded by the virtual world's explicit rewards for certain aesthetic choices (more likes or comments), are part of a constellation that perpetuates ambitions for "the perfect little-girl pout, rounder and larger-looking eyes, even [reshaping] our jaws to provide a slimmer, more childlike physique,” says Dr. Sharp.

In western culture, the infant aspect is often further reinforced. “These literal transformations added to the techniques of infantilisation that already existed, such as posing female models with their fingers or lollipops in their mouths, or dressing them in Mary Jane shoes, ruffled socks, and clothing inspired by the schoolgirl uniforms worn by actual school-aged girls.”

Advertising and social media did not create these standards; they are simply new vehicles. What is new is that digital tools democratise those standards across age groups. We ensure Lolita stays a seductive little girl … and in doing so, continue to nourish those who fetishise and exploit her.

Lolita Syndrome 2.0

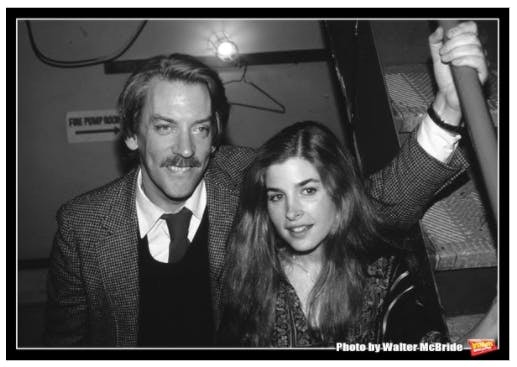

The aforementioned "Lolita" play appeared on Broadway in the early 1980s. It drew criticism from activists, doctors, authors, and social workers, denouncing what they referred to as "Lolita syndrome,” or “the rapidly-growing number of images that make sexual objects out of little girls and legitimise their sexual abuse." In a 1981 New York Times article, Dorchen Leidholdt, founder of Women Against Pornography, lamented, "What worries us is that people are starting to regard these images as normal."

Donald Sutherland and Blanche Baker backstage after the March 19, 1981 opening night performance of "Lolita" at the Brooks Atkinson Theatre in New York City. Image by Walter McBride.

Likewise, Dr. Helen Rodriguez-Trias, a pediatrician who worked with sexually abused children, commented, "The play trivialises, and thus legitimises, the exploitation of children and violence against women at a time when conscious men and women are uniting to expose these evils." Jerry Sherlock, the play's producer, defended it: "It doesn't pander and it doesn't legitimise … And let's face it, there's nothing new about this kind of relationship: It existed in the past, it's still with us, and it will exist until the end of time."

We need not resign ourselves to Sherlock's view of eternity, but certainly Lolita adapts to time’s conveniences. Infantilised beauty was “Lolita syndrome” in the 1980s; today, with, social media filters and increased attention to mental health, we only relabelled it “Snapchat dysmorphia.” It is no surprise that I see my childhood in these filters: In 2007, eerily echoing comments on "Lolita," the American Psychological Association cautioned that Bratz dolls could influence body image and the "over-sexualisation of young girls." Most beauty filters manipulated my characteristics to give me a narrower nose, plumper lips, bigger eyes, clearer skin, as if stamping me with Bratz features. This comparison is not mere imagination; in 2019, the “Bratz doll challenge,” a social media trend, was all about making yourself look as much like the dolls as possible. Talk about Lolita Syndrome 2.0—except instead of someone imposing it upon us, we can do it to ourselves in seconds.

Tech facilitates convenience. If the look is desirable, it will cater to it. And filters do not just filter faces; they can filter reality at scale. Newer versions of the iPhone, from iPhone 11 onward with iOS 13, modify selfies in real-time, brightening your face and clearing your skin. Users must manually opt out of the feature, cynically titled “lens correction”: “When you take a selfie with the front-facing camera or a photo with the Ultra Wide (0.5x) lens, it automatically enhances the photos to make them appear more natural,” Apple Support writes. “To turn this off, go to Settings > Camera and turn off Lens Correction.” Soon it may be difficult to ever truly see our own faces … or worse, tolerate the sight of them without modification.

What happens when such characteristics become the only valid way to be? Ever-growing makeup trends and cheaper plastic surgery make it much simpler to pass from filter to direct modification, enabling us to align reality neatly to illusion. At the same time, that choice is not so much a choice but a reflection of what our culture, with its seemingly endless choices, has decided is best: Lolita 2.0, the human Bratz doll.

Makeup artist Ania Szlaga's rendition of a Bratz-inspired look.

Filters may groom younger users for more invasive operations later. An August 2020 survey by Girlguiding found that 39 percent of girls and young women (11-21) feel "upset" they can't look as they do online. Eight out of 10 "revealed they had considered changing how they look."

A land of infantilised adults

Whatever you wish to call it—Lolita Syndrome, Snapchat Dysmorphia, Bratz Doll Syndrome—the infantilisation of beauty may merely be the symptom of a larger 21st century phenomenon, engineered in the United States: The infantilisation of adults.

Tech advancement is driven by the idea that if we want something, we can expect to have it, regardless of the risks it poses to ourselves or others—part of what writer and philosopher Ben Cain calls "mass infantilisation.” While the United States, with Big Tech and Silicon Valley, seems central to this process, it’s a global phenomenon, Cain says; the country's power and prominence have turned the western world into a monoculture.

“The American masses are susceptible to being infantilised,” Cain says. “Their radical Protestant traditions and their country's founding narrative tell them they're on their own; they're babes in the woods and as long as they feel free to do mostly whatever they want, they're content to pursue only the narrowest, most short-sighted goals.” This myopic tendency, which romanticises the individual over the community, subtly also puts profit over people, with “manufactured cravings that can never be truly fulfilled, since each is hollow and easily replaced by another disposable one. And all of which is facilitated by a steady stream of fallacious, associative advertising.”

The rise of people asking plastic surgeons to make them look like filters is among these manufactured cravings, "personal" preferences that actually trickle down from larger marketing messages. Sure, filters are disposable; they are “choices,” as tech firms are always careful to mention. But these choices become more probable when combined with the pressure engineers face to gamify our experiences (pdf) to keep us online and consuming. Reeling mental health effects and surgery—the natural outcomes of these facilitated choices—are less disposable.

This infantilisation is subtly diffused to the rest of the world. During former president Donald Trump’s tenure, we saw the irony especially in its victory lap through the Capitol. “[I]f you prefer truthiness to truth because you're stuck in a solipsistic, evangelical or libertarian mindset,” adds Cain, “you won't even care that you're not learning much of anything. You’ll be like a baby, content with simple pleasures.”

Facing up to reality

De-infantilising ourselves

One solution lies in changing definitions of liberty, says Cain. "As much as we boast that we're free in the developed world to buy or to say this or that, that independence is a profound weakness if it's divorced from a more responsible kind of autonomy.” Direct action could include reducing tech monopolies, or simply recognising unpleasant and inconvenient truths. "Of course, we'd rather be free to come or go as we please rather than be subjected to the whims of a totalitarian state. But we should also want to be limited by reality and to know ourselves in the ancient sense, to recognise we're limited by what we are."

While technology might appear to give us unfettered access to power, if 2020 proved anything, it’s that we’re all susceptible to something as simple as a virus, and our freedom is constrained by the values of the larger culture we are part of. Community is not something one opts out of; it is a given, whether we are conscious of our relationship to it or not.

The question becomes how we can divest ourselves of infantilisation, and invest in healthier, more diverse social mores and beauty standards. In a post-pandemic world, there are calls for limits on Big Tech, Reddit users dumbfounding short sellers, and societies trying to figure out how to reconcile ambition with biological vulnerability.

Large-scale changes are needed, but that doesn’t mean smaller ones aren’t valuable. Digital strategist Kaitlin Maud, whose 2013 TEDx Talk popularised the concept of digital anthropology, says people are challenging infantilised beauty by demanding a wider definition of beauty from media. "I think [the democratisation of technology] has really helped push us toward a more broad definition of femininity in general,” with bodies of various shapes, sizes, colours, and gender identities shown and appreciated in advertising, television, and film, she observes, adding that we can continue in this vein by compelling companies to broaden what they consider “acceptable” notions of beauty.

"Magazines (like Seventeen) and beauty companies (like ModCloth and CVS) have committed to transparency around photo retouching as a result of pressure from their primary consumer base,” Maud adds. “We are seeing the same thing happen now, with social media users joining together to ask companies to expand beyond straight sizes and show models of different body types wearing garments. They are doing the same by communicating their expectations that brands in the beauty space commit to racial and ethnic diversity in both models casted and in ranges of colours offered in cosmetic products."

Companies and apps may continue to prey on our affinities, including the tendency to lean into infantilisation. But if consumers can propagate Bratz Doll, or Lolita, Syndrome through phones, they can also help curb it. In September 2020, makeup artist and curve model Sasha Pallari launched her #FILTERDROP Instagram campaign, urging followers and women everywhere to celebrate themselves without digital manipulation. By early December, almost 2.000 posts bore the hashtag.

In a BBC interview, Pallari said, "For me it's no issue putting up a photo with no makeup on, and not using a filter, but for some of these women who have done it … well, one said it was scarier than having a baby."

16 Apr 2021

-

Sarah Simon

Illustrations by Sarah Simon.

DATA-DRIVEN TECH & SOCIAL TRENDS. DISCOVERED WEEKLY. DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX.

02/03

Related Insights

03/03

L’Atelier is a data intelligence company based in Paris.

We use advanced machine learning and generative AI to identify emerging technologies and analyse their impact on countries, companies, and capital.