Managed Out by Anti-Bias Tools: The Selective Service of Recruitment AI

TOPICS

Social MobilityIn September 2019, I was in Washington, D.C. for The Atlantic Festival, and fell in love with the city. I began applying for journalism jobs there. One company invited me to an interview process where artificial intelligence (AI) software would be a required component in three out of four steps.

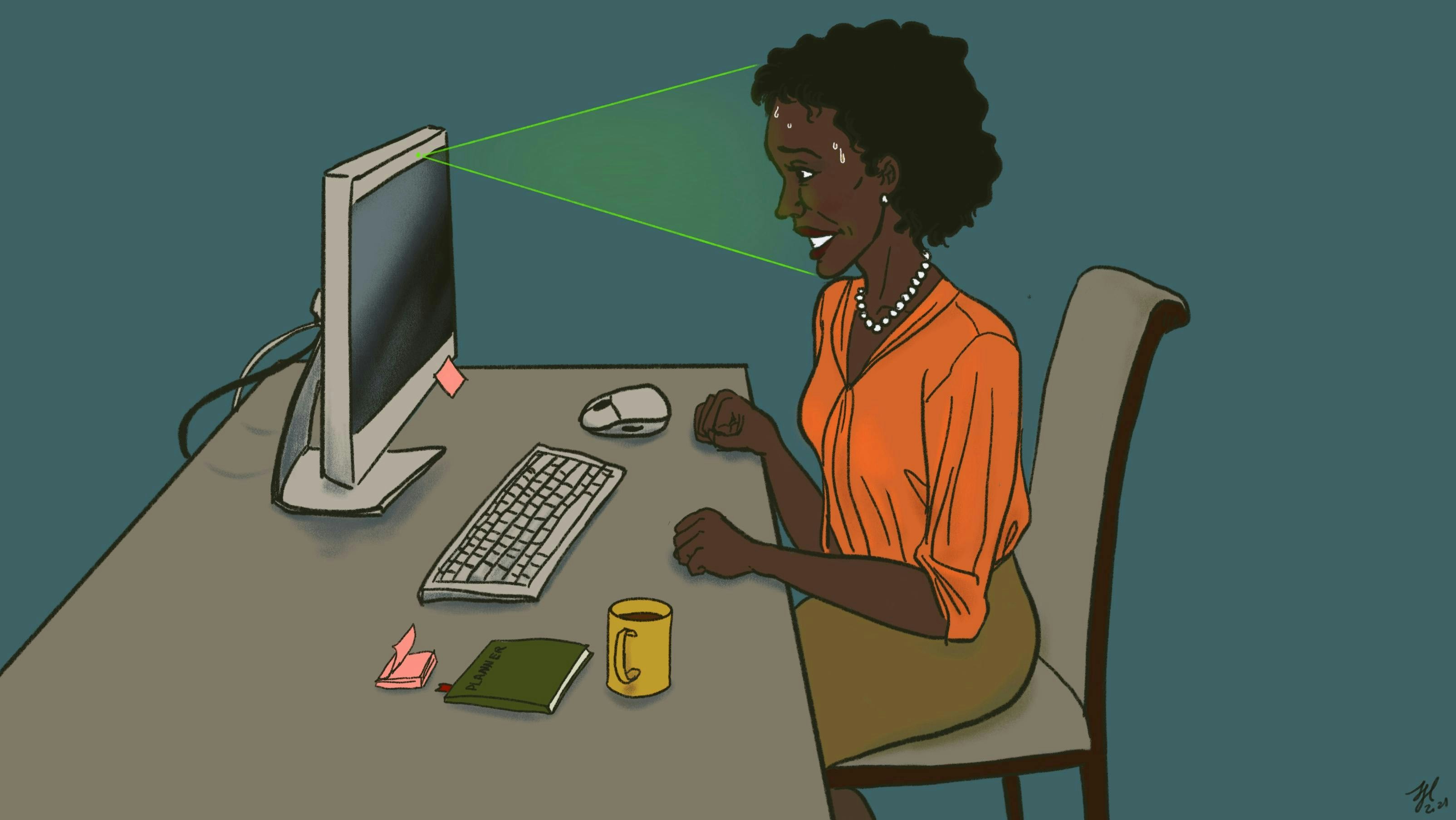

As a black woman past the age of 40, I knew I was highly susceptible to biases built into this software, even as a member of a triple-protected class with a background in law, computer technology, and intellectual property. The company’s aggressive push towards its AI software prompted my loss of interest in the job, and to some degree, the job-seeking process itself.

This is not an anodyne example.

Joy Buolamwini, founder of the Algorithmic Justice League and researcher at the MIT Media Lab, discovered that facial recognition software recognised her face when she put on a white mask, and would not recognise her face without it. In collaboration with AI ethicist Timnit Gebru, the pair found a near 35 percent error rate in facial recognition software when it came to people with darker skin, but near 100 percent accuracy when identifying white men. Gebru discusses the analysis in the Design Better podcast.

In "A Case for Banning Facial Recognition," Gebru—who was recently terminated by Google—says, “I’m a black woman living in the U.S. who has dealt with serious consequences of racism. Facial recognition is being used against the black community."

This builds on an observation from Buolamwini, who, in the New York Times article that described their research, stated, "You can’t have ethical AI that’s not inclusive, and whoever is creating the technology is setting the standards.”

Similarly, a black computer science student took to Twitter in a thread sharing her then-recent experience, misgivings, and distrust of AI-based software, particularly the HireVue tool, writing, “As a dark-skinned black woman, I feel like I've already been filtered out.”

A history of abused trust

In the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, artificial intelligence surges in popularity. It has become standard in workforce management, exponentially so amid travel restrictions, and as a defence against the spread of COVID-19.

Recruitment AI builds an idealised “model,” then seeks close characteristic matches. If you’re reading this while black, you already see the problem. A workforce built through AI hardens the status quo of white homogeneity where black hires just aren’t a “culture fit.” (Hat tip to every recruiter we know.)

The United States' generational chattel slavery, Jim Crow laws, and crack cocaine distribution throughout black communities, followed by addiction, the 1994 crime bill, mass incarceration, and overall disenfranchisement without reparations has produced the relative poverty of blacks in the United States. The systemically-orchestrated and uncomfortably thin black “wealth cushion” that pre-dates AI have sown deep distrust. For this community, recruitment AI presents another "Black Tax."

“Many scientists today continue to downplay or outright erase the role science has played in perpetuating anti-black racism and violence,” per Scientific American, but science-based harms on black people isn’t new. In societies replete with histories of race and science, often in combination, we knew—or should have known—that the fusion of AI with workforce management, law enforcement, and the processing of federal benefits would multiply the collective burden on black people, while perpetuating and reinforcing the race-based wage gap.

Daily, in most any transaction, black people battle racism, discrimination, and prejudice from typically non-black human decision makers. Now, through AI, blacks also suffer the effects of negative bias built into "anti-bias" tools, compounding vulnerabilities, obstacles, and worries among black job seekers.

A study of data privacy sensitivities found that its lowest-earning participants were “acutely aware of a range of digital privacy harms,” and “not knowing what personal information is being collected about them or how it is being used made them ‘very concerned’.” Still, in a kind of tacit agreement for the slightest chance at job offers, desperate job seekers feel pressure to comply with invasive, marginalising, and mandatory algorithmic proddings of AI-based pre-employment and job interview software.

Industry experts Michele Gilman, professor of law with focus on privacy, poverty, and civil advocacy at the University of Baltimore; and Hector Dominguez, the open data coordinator at Smart City PDX in Portland, bring their concerns to this conversation about workplace AI—celebrated for its time-cost benefit, adding rocket fuel to underlying disparities.

Human bias in AI design

Machine learning is the rocket fuel of AI. Importantly, these machines “learn” what human beings teach them. According to Dominguez, this “learning” produces “historical values,” including the conditioning of those human teachers; and implicit “values”—such as racism, prejudice, and other biases—build “models” which provide conclusions that aim to mimic human decision-making.

Human bias is inherent to conclusions derived from AI. “Inequities arise when algorithms reinforce divides in economic status or result in discrimination against marginalized groups. These tools add scope, scale, and speed to long-standing economic vulnerabilities [...] thus making it harder for low-income people to move up the economic ladder,” Gilman observes in Five Privacy Principles of GDPR the US Should Adopt.

The designers and programmers of those algorithms—and even the subjects who compose the data that trains them—are disproportionately white (or Asian) men, adds Gilman, who, on the development side, often lack the contextual ability to recognise and correct their own biases. Tawana Petty, the national organising Director at Data for Black Lives, notes AI decision-making is a replication of racial bias that starts with humans, then is programmed into technology.

White men dominate the maker space for “anti-bias” tools, comprising about 39 percent of professionals, 47 percent of managers and 59 percent of executives in the field. White women’s jobs also remain relatively consistent; compared to other women in technical roles, they receive more opportunities to enter management.

End users of AI hiring technology prioritise ROI by requiring data subjects’ engagement with it. Coupled with facial recognition technology, shown to reinforce bias against black people, this is a strong-arm tactic that exaggerates pre-existing imbalances of power.

Gilman says data privacy has been violated for decades in ways that affect daily life, particularly among underrepresented communities. What’s worse, “Any ‘consent’ is meaningless because applicants lack the ability to negotiate the terms which are set by employers, and when hiring is done with an algorithm, job applicants lose protections.”

In an article on how natural language processing, often an element in AI-based software, also incorporates unconscious conditioning, Towards Data Science illustrated several other examples of bias it found in its models:

- According to machine learning models, black is to criminal as Caucasian is to police. [Source]

- According to machine learning models, lawful is to Christianity as terrorist is to Islamic. [Source]

- Tweets written by African Americans are more likely to be flagged as offensive by AI. [Source]

Yet the promise of AI remains seductive from a corporate perspective. The multinational company Unilever saved about $1M and 100.000 hours of recruitment time when it replaced human recruiters with AI software, according to The Guardian... human cost be damned.

Companies using recruitment AI are not just saving money; they could also be making some. Gilman says, “[Companies] may be sharing and selling [job seekers’] data to other entities without [job seekers’] knowledge. Even if you strip a resume screening algorithm of race and gender indicators, there are numerous proxy variables that can substitute for the illegal inferences, such as name, zip code, and education.” They may also “use that data to continue to train their models”—which, Gilman says, is a clear violation of privacy.

The point at which we become the algorithm is 100 percent utilitarian, Dominguez observes, and it dehumanises lives and relationships.

“The irony of the digital age is that it’s caused us to reflect on what it is to be human.” David Polgar, Tech Ethicist.

The path to legal remedy

Compulsory job seeker interaction with these platforms is an indicator of shrinking civil liberties and civil rights. The Fourth Amendment affords protection against unreasonable search and seizure, depending on citizenship, but The Perpetual Line Up notes that whether facial recognition technology constitutes a “search” is a question that state and federal courts have yet to answer.

Gilman’s concerns with automated hiring are many, but she’s also seen clients denied benefits based on algorithms that are not transparent. "The proprietary claims of trade secrecy privilege [intellectual property] over people,” says Gilman. Details on weighted characteristics are lacking. “We don’t know what the algorithms are measuring or how various factors are being weighed.”

Those farthest from justice are detrimentally impacted by this technology, which was rushed to the marketplace without adequate trials. Companies using recruitment AI know that data subjects of any kind might find it intimidating, even impossible, to prove liability under Title VII, which provides injunctive relief against discrimination in specific public contexts, and was also designed to facilitate equal employment opportunities. Gilman wants to see legislative action for “people who are marginalised, who experience privacy differently.”

In Manipulating Opportunity, Pauline Kim, professor of workplace law at Washington University in St. Louis, writes, “Understanding the harms and benefits of automated decision making requires examining the entire process of development of these predictive tools, beginning at the design stage, rather than after deployment, when problematic elements of these technologies would be difficult to isolate and extract from [...] a ‘Black Box’ after they are operating in the real world.”

This “Black Box” operation of AI is a grossly unethical industry norm.

“Absent a very strong federal privacy law, we’re all screwed.” Al Gidari, Stanford Law School professor specialising in privacy issues.

According to State of AI, “For the biggest tech companies, their code is usually intertwined with proprietary scaling infrastructure that cannot be released.” Cannot or will not? Existing privacy protections for the makers of these technologies, combined with justifications from end users, is an evil irony.

The paper “Why are we using Black Box models in AI when we don’t have to? A Lesson from an Explainable AI Competition” boldly debunks the much-propagandised AI “Black Box." Co-authors Cynthia Rudin, professor of computer science at Duke University, and Joanna Radin, professor of history at Yale University, expound:

“Few question these models because their designers claim the models need to be complicated in order to be accurate. [...] The belief that accuracy must be sacrificed for interpretability is inaccurate [and] has allowed companies to market and sell proprietary or complicated Black Box models for high-stakes decisions when very simple interpretable models exist for the same tasks [...] allowing the model creators to profit without considering harmful consequences to the affected individuals.”

Many are lobbying and advocating for proactive regulatory approaches to address concerns about fairness and bias in algorithmic systems. Illinois’ Artificial Intelligence Video Interview Act, a template for the nation, governs the use of AI in job interviews. It applies to companies that “asks applicants to record video interviews and uses an artificial intelligence analysis of the applicant-submitted videos.”

Effective January 1, 2020, AIVIA also limits sharing of those videos, and requires destruction of the same upon request.

Rethinking our pact with algorithms

At Smart City PDX, Dominguez helps establish privacy policy and procedures concerning facial recognition and surveillance technologies used by local government agencies. Guiding principles of SCPDX dictate that data and technology projects be transparent, measurable, ethical, and meet the needs of the community. Paramount "is the work we need to do before we deploy new technology, especially in BIPOC communities,” says Kevin Martin, who leads the organisation.

SCPDX has banned both private and government use of facial recognition technology in Portland’s public places.

In an episode of The Data Science Podcast, Dominguez talks about Ursula Le Guin’s The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas, which describes “a really happy town where everyone is prosperous, but all of this depends on the suffering of one individual, and everybody knows it.”

The moral of the story, he explains, is empathy. “Ethics can help get us to the next step of fairness in technology, but ethics is not enough, because ethics is not empathy. We are all connected, and we all have a responsibility to make humanity thrive. We must exercise our empathy muscles to understand the other side, [to] care for each other, because what we’re trying to do is incorporate the complexities of human society in ethical frameworks.”

Pioneering technology that “optimises” discriminatory decision-making is rogue science, contributing again to histories of systemic injustice, but a conscientious humanity can and will right this science at scale.

That will be true innovation.

04 Mar 2021

-

Carla Bell

Illustrations by Frankie Huang.

DATA-DRIVEN TECH & SOCIAL TRENDS. DISCOVERED WEEKLY. DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX.

02/03

Related Insights

03/03

L’Atelier is a data intelligence company based in Paris.

We use advanced machine learning and generative AI to identify emerging technologies and analyse their impact on countries, companies, and capital.