Simulate this! When digital twin technology goes human

How people think about technology impacts the world around us. It shapes public response to innovation, attitudes towards what is technologically possible, even beliefs about what kinds of futures are desirable.

But by revealing implicit cultural values, these sociotechnical imaginaries also provide powerful metaphors for thinking about the social worlds we already inhabit. In industrialised societies, simulation is one such sociotechnical imaginary.

Examples of the simulation imaginary abound in popular culture. It is central to Isaac Asimov’s notion of psychohistory, still cited as both motivation and model for many contemporary attempts to leverage massive computing power and vast datasets for predictive ends. Anyone who has seen The Matrix—and even those who haven’t—will likely recognise the metaphor in action when a “red pill” is used to evoke someone’s willingness to learn potentially unsettling truths about reality.

Simulation as a concept also suffuses philosophy and social thought. French philosopher Jean Baudrillard saw the postmodern condition as a consumerist age of simulation, where boundaries between the authentic and artificial are dismantled in ways that will eventually become indistinguishable to human consciousness—a state he termed hyperreality. Sherry Turkle, too, described industrialised society as characterised by a culture of simulation.

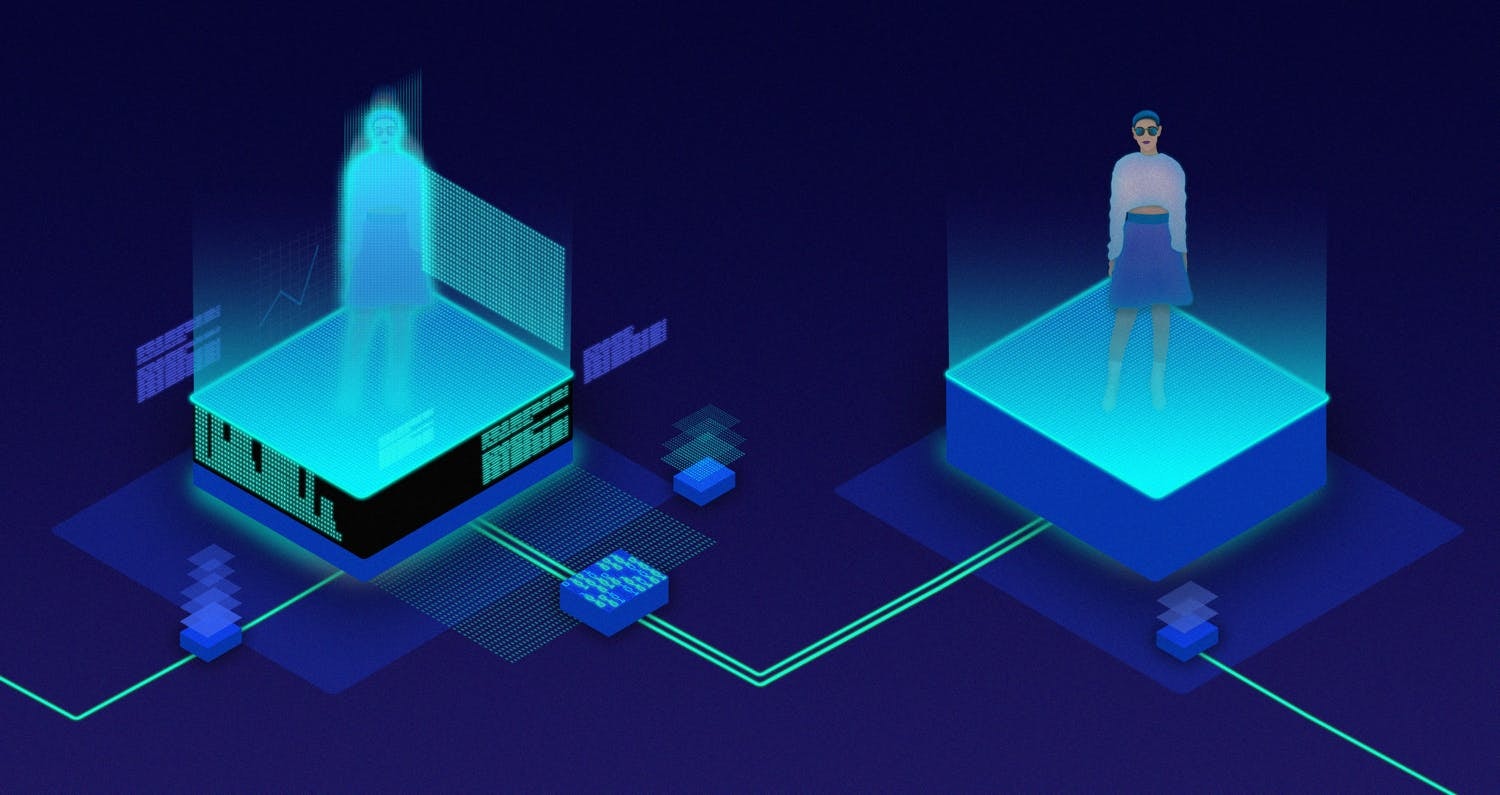

Digital twins—virtual representations of physical objects, wedding real-world data feeds with simulation modelling—literalise the metaphor of simulation. Their underlying technology enables them to monitor physical systems in real-time, but they also portend the capacity to virtually replicate humans and human decision-making.

From a digital anthropology perspective, what kinds of practical and ethical issues does their development raise?

Emerging applications of digital twins

Digital twins are deployed, or are in development, in a broad range of areas. In manufacturing, they are found in activities related to design, maintenance and process rationalisation and improvement. In construction, digital twins contribute significantly to optimisation and efficiency. In the automotive industry, Tesla deploys digital twins of each of its cars to ensure safe, comfortable functioning via bespoke software updates, driven by real-time data from individual vehicles.

As digital twin techniques advance, the practice moves into the realm of higher fidelity world-building, not only in terms of spatial scale but also extended temporalities. Destination Earth seeks to model natural and human activity at a global scale by producing a digital twin of Earth itself.

Meanwhile, digital twins can project us into different timeframes, with the potential to serve as tools for visualising historical events, as well as predicting future events.

Toying with immortality: Human digital twins

AI can bring digital twins to life in ways impossible for earlier forms of virtual representation. This can be figurative, as in engineering tasks related to maintenance or optimisation. But it can also refer to mechanisms mostly still being developed for imbuing human digital twins with synthetic agency. Such tools present an opportunity for generating techniques of automated interaction, where AI-powered human digital twins could become a proxy for actually existing agents—including not only physical people, but approximations of their thoughts and feelings.

This has political relevance. According to a growing body of literature on democratic engagement, attempts to achieve consensus through established mechanisms of political participation are increasingly marred by disruptive factors, like polarisation and misinformation. In this context, digital twins have been proposed as a way to arrive at new forms of simulation-driven consensus. This could redefine ideas of democratic legitimacy, including the role non-human agents play in politics and governance.

Human digital twins can serve as proxies in more general ways—notably in the form of AI assistants, which let people perform multiple actions at once by effectively distributing decision-making processes. But they are not less morally challenging. Artificially intelligent copies of humans, who could live on in a form of digital afterlife, raises the spectre of something verging on immortality, disrupting some supposedly universal characteristics of being human—to be born, to live, to die.

The question of mortality is not limited to the domain of the afterlife. Dystopian science fiction is replete with representations of inequality in healthcare and disease prevention. See, for example, the gross inequality depicted in Neill Blompkamp’s Elysium.

We already see the principles of such disparities in many places, even in putatively advanced industrial societies. In the United States, unequal access to healthcare is linked to large numbers of excess deaths annually. According to one study, lack of health insurance was linked to 25.180 excess deaths between 2016 and 2019.

If the health benefits afforded by human digital twins are equally unevenly distributed, the impact will be more detrimental, for greater numbers of people. For those unable to access these technologies, such a discrepancy will reproduce the digital divides that already plague access to emerging technologies. In this case, however, it will do so in ways far more explicitly vital.

Processes related to digital twins are heavily data-intensive, raising practical questions about data ownership and management: what will be done with the data upon which human digital twins rely, how will it be managed, and to whom does it belong?

Some models of this technology envisage a context where users own the data that powers their digital twin. However, existing applications demonstrate that such a paradigm of data ownership is unlikely to become dominant in the short-term, though we see signs of movement in that direction.

Further issues arise around ownership and control over one’s likeness. Existing, evolving technology in the field of deepfakes introduces the notion of “copies” of originals that never existed—in Baudrillard’s terminology, not just simulations, but simulacra. This challenges a discourse of authenticity that is prominent in Western mass culture, where fidelity to the “real”—and to oneself—is presented as one benchmark against which creativity’s value is measured.

Abusive applications of deepfake techniques, like simulated revenge porn, highlight how human digital twins may get enmeshed in emerging structures of harassment and harm. The gendered dimensions of such abuse are tangible, a reminder that it is not just people or things we reproduce and amplify through these technologies, but also structures of exploitation and exclusion within contemporary society.

Ethical futures and open questions

Since digital twins are presented as instrumental to the fourth industrial revolution, we must ask what forms of empowerment they facilitate and how we can ensure their benefits are equitably realised. What kinds of experiences can human digital twins enable? This is an ethical and moral question, certainly, but it is also a matter of design and imagination—of technology and process, as well as policy and regulation. All have a bearing on the shape of these technologies, and the social relations they will help cultivate.

Studies of algorithmic bias already point to our profound failure to produce equitable systems rooted in the extraction, processing and management of human data. Discriminatory algorithms, which learn from the innumerable chauvinisms of human information systems, exclude minorities from basic essential services—whether applying for a job, a loan or even a passport. Such inequities have led to campaigns for data justice that bridge the political and technical.

These issues demand coherent, considered responses. Attempts to provide oversight are already taking shape within the EU, with examples like the Digital Services Act and proposed regulations of artificial intelligence. Concepts of cybersecurity are also shifting to include coverage for our digital twins.

Still, in reality, until such time as we see a transformational shift in regimes of data ownership, data security and sovereignty will remain domains of uncertainty. Data breaches of national health systems, such as the one ongoing in Ireland, only serve to underline this fact.

These changes also raise questions about self and identity that are sure to perplex anthropologists and anyone with an interest in what it means to be human. As a discipline rooted in engaging with the lives of actual people, anthropology has critical reflections to make about the status of virtual personhood. The prospect of human digital twins makes this a more pressing reckoning, with the power to broadly transform the meaning of personhood ... and our assumptions about who—and what—the term applies to.

17 Sep 2021

-

Anthony Kelly

Illustrations by Dominika Haas.

DATA-DRIVEN TECH & SOCIAL TRENDS. DISCOVERED WEEKLY. DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX.

02/03

Related Insights

03/03

L’Atelier is a data intelligence company based in Paris.

We use advanced machine learning and generative AI to identify emerging technologies and analyse their impact on countries, companies, and capital.