Brand me: Digital selves and the transformation of identity

In January 2020, Dolly Parton made an Instagram post featuring a grid of four images she suggested could be her profile pictures on four platforms. It spawned a meme—the “Dolly Parton Challenge” or “LinkedIn Facebook Instagram Tinder”—that became a global sensation.

Before Parton’s post, people compared profile photos across different social accounts in similar ways. But this meme highlighted, in a uniquely formulaic way, how our self-presentation changes as we move from platform to platform.

This practice of performing distinct selves may be something digital platforms bring to the fore, but it is true beyond digital environments. Over 60 years ago, Erving Goffman published The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. It raised an important distinction between the selves we perform when in the view of others, and those that are “backstage”—who we are when unobserved.

People understand this reality implicitly, which Parton’s meme makes clear. But the meme also underscored the sometimes oppressive expectations of uniformity that characterise contemporary attitudes towards presentation of self online: The need to foster a unique and stable personal brand, a fully-consumable self. It also draws attention to the tensions these expectations produce in terms of what should or should not be shown in order to appear coherent in an authentic way.

People make all sorts of judgments about the multiplicity of online personhood, a topic that has enjoyed long debate. Compare the divergent positions of founders Mark Zuckerberg (Facebook) and Christopher “Moot” Poole (4chan) regarding online anonymity. Judgments will continue to differ.

We’re interested in thinking about what this will mean for what people think identity is. This is important because people’s attitudes towards digital selfhood and identity shall likely impact how technologies are used.

Is identity in the online world so different from the offline one? Below, we discuss some reasons why we think digital selves do and don’t represent something transformative in how we see and understand identity, before looking to the future to consider where things might go.

The more things stay the same...

Nathalie Béchet: Deploying various facets of the self is a well-known psychological phenomenon. JR Suler argued that “a single person's identity embodies multiplicity,” given the many roles any person plays in their life.

Role theory suggests that playing with diverse personas is a healthy practice of self-building. In social psychology, this represents “how a successful life is an efficient juggling of the various tasks and positions we accumulate and develop from childhood through adulthood.”

It is reasonable to perceive the internet, including social media, as an extended playground for such practices—what JA Bargh referred to as “a kind of virtual laboratory for exploring and experimenting with different versions of self.” If you look at things this way, the multiplicity of digital selfhood isn’t particularly new.

Anthony Kelly: The idea that we have one “true” self is problematic. Not long after the birth of the internet, Pierre Bourdieu wrote about the “biographical illusion,” where we seek to make life’s chaos into something one-dimensional and ordered. From Bourdieu’s standpoint, life is falsely viewed as coherent, straightforward and—particularly in Western cultures—inescapably individual. He argues this is actually an artefact of how we structure narratives about selfhood.

We can think about this in relation to the debate about anonymity mentioned earlier. That online personas should be equated with biographical individuals can be understood when considering that alignment between virtual and actual selves serves the interests of platform ecosystems, built on the monetisation of personal data.

So Facebook’s position on online anonymity is also a stance on the political economy of platforms, and the digital labour of users they invariably rely on. But the stance is made by orienting towards a tension that long precedes the web.

NB: Speaking of social networks, as the distinction between “online” and “offline” vanishes, we now treat social networks like any other space, defined by codes of conduct. It has been a learning process, and it makes sense. Just as we are taught to dress and act differently in front of friends, grandparents or employers, we learn to appear and converse differently on Facebook, LinkedIn or Tinder.

Sociologists like Goffman, and psychologists like William James, underline this multiplicity of personhood. It can be detrimental to idealise a past where people were "freer" to be true to themselves and others. It is historically inaccurate—masquerades and identity games have always existed.

Consider Robert Fortune, who, in the mid-19th century, disguised himself to infiltrate Chinese tea makers for the British; or the alleged Dutch spy who went by the Malay name of Mata Hari, and fooled everyone into thinking she was of “Far Eastern” descent. Not to mention Charles Ponzi, whose last name became synonymous with the greatest financial scams in history.

Also, this fantasy of a single-identity past undermines our complexity. The myriad digital mirrors we interact with, since the birth of the internet, present different sets of rules for the definition of self. We now negotiate our multiple online selves with a sort of “cyber grammar.”

AK: We also see this kind of thing elsewhere. I’m thinking not only of the imaginary selves we inhabit or perform through play—for example, roleplay in virtual worlds—but also posturing related to self-presentation on platforms. When we look at these practices of differentiation, we see that differences aren’t just between platforms, but are palpable on even one platform.

One example is the practice of alt and main profiles on Twitter. Twitter is considering piloting a mechanism for filtering audiences for tweets. And Instagram is seeking to mainstream the practice of creating finstas, by encouraging some users to segment their audience by creating another account.

For me, this speaks to Nathalie’s comments about a cyber grammar or a notion of platform repertoires, specifically in how it highlights the significant regulations that shape participation in online spaces.

But this also happens in analogue environments. Often it is not necessarily a question of play, but of necessity, like people being pressured into hiding their sexuality.

NB: It seems to me that debates around presenting your “best self” instead of your “true self” often implies photographs. This is embedded in one of photography’s inherent properties, which is that you capture a singularity.

In a study of Mongolian photographs and how they edit them, anthropologists Gregory Delaplace and Vincent Micoud concluded that photographs depend on a form of “demonstration mode.” Since human faces still can’t look like Picasso’s paintings—to my knowledge—this means you can only have one profile photographed at once, and naturally, would favour the best one. So you make choices: Setting, lighting, angle, outfits.

You elaborate a constructed self that may vary by situation. It is a common and familiar practice.

AK: Visuality also links with specific communication practices through which digital selves get articulated, whether through text, images, video or audio—something we see increasingly through the rise of Clubhouse and the audio-based competition space it created.

Digital selfhood is inescapably mediated. Nathalie’s photography example highlights one way people were historically represented as media objects. The materiality of images makes this mediation more tangible. But such mediation exists everywhere, even when not easily perceptible.

This echoes one core tenet of digital anthropology as outlined by Daniel Miller and Heather Horst. It proposes that culture is always mediated, and understanding the mediations that characterise digital culture can help us avoid falling into the trap of viewing the analogue as authentic sociality.

Currently, major transformation is occurring in the mechanisms by which life and lives get mediated. Which makes it a good moment to think about some of the ways digital selfhood marks a break from an older status quo.

...the more things change

NB: Online spaces enable instant direct reaction to those digital pebbles we sow, both from people we know and from strangers. This is new in its scale and magnitude. Unsolicited public commentary definitely existed before social media—consider street harassment—but spaces, like public Instagram or Twitter accounts, enabled, if not fostered, this permanent external evaluation. There are now multiple online levers others can activate to evaluate our online selves: Likes, comments, shares, repost, tags, mentions, followers, etc.

Being evaluated the wrong way can go as far as being “cyberbullied,” signalling the intimacy of the relationship between our online and offline selves. Or you can be “cancelled”—ostracisation in social or professional circles, online or offline. These tools can create a sentiment of being constantly scrutinised, and the potential of being badly evaluated.

These are linked to rising indications of narcissism, body dysmorphia and even digital self harm. Social thinkers and industry figures note a form of “staging of the self,” as if users are being pressured to act like brands.

Is it to mimic influencers, or because of some essential features of social media? Hard to say, but it manifests in the curation of Instagram feeds, for instance: With the right choice of colour palette, consistent filters, consistent theme, and a “je ne sais quoi” to stand out… boom! You just found the perfect way to promote your online self and be consumed by others.

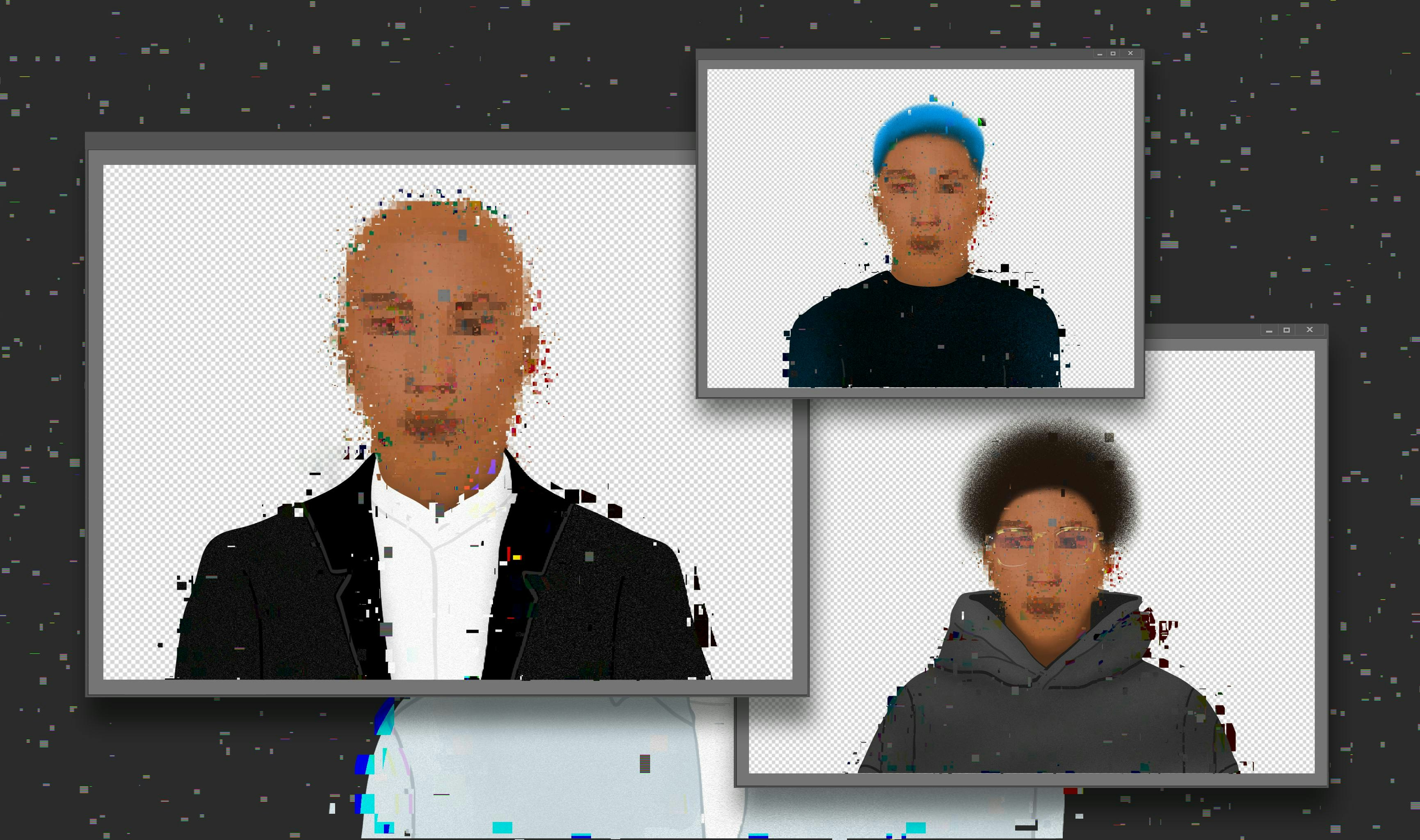

AK: Aside from the selves we want seen, the shift towards digital participation also brings to mind a set of invisible “shadow” selves, aggregated through platform data surveillance practices—that is, images of us produced by platforms, either through our own practices, not explicitly oriented towards self-presentation (for example, keystrokes); or through platform practices, by which images of us are produced in our absence, or unbeknownst to us.

The difficulty with these datafied forms of selfhood is that they are frequently fully divorced from user control. Many may even be unaware of their existence. They have serious implications for notions of public and private, and raise the issue of intentionality, something within which many cultural models of selfhood are rooted.

Is it still possible to be your “self” when the artefact in question is something separate? Here we consider some of the questions around data and ownership I'll discuss in a future piece on simulation.

NB: Regarding Anthony’s comment about “shadow selves” built from aggregated data, we now also have tangible digital tracks of past versions of “us” that we are arguably still accountable for in the present. The digital crumbs of past usses are now stored forever, and we might have to justify them.

This is part of what makes “cancel culture” possible. Of course, before the internet, people could still find artefacts linked to your past (an object, a voice recording, a letter or past acquaintances who knew you), but does it compare to the modern possibility of someone crawling your entire Facebook or Twitter, and discovering that, in 2008, you posted a picture of yourself blackfacing with friends?

The fear of constant quantified peer evaluation, and the resulting obsessive goal for coherence (even through time), has set the online definition of self apart from previous ways we used to define ourselves.

AK: The idea of a “cancelled self” feels of this moment, and the particular confluence of digital culture and digital affordance that characterises it. That’s linked in large part to the capacity we acquire through platforms to surveil others.

On one hand, we can think about an explosion in mechanisms for datafying and quantifying the self through health-tracking tech or other sensory records of one’s physical or digital activities. On the other, there’s the set of traces, accessible by others. These can be wrapped in forms of social hygiene, explicitly facilitated by platforms.

A good example of this is a website designed to highlight who amongst your Facebook friends liked the page of Donald Trump, launched when Trump was still frontrunner for the Republican nomination in the US in 2015. Similar mechanisms exist on Twitter, allowing users to identify connections who are followers of personae non grata—the cancelled.

This can be a highly dynamic category, in practice. These tendencies towards certain forms of visibility also mean it’s easier for others to produce versions of you from the tracks you leave behind in data, and raises its own set of problems.

NB: The intangible nature of digital adds an extra layer of complexity. Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic noted how “identity, style and values were mainly revealed by our material possessions”—an extended self that relies on human inference to turn symbolic signals into a personality profile. Anonymity, the absence of physical bodies, delayed photos (in space and time), edited photos: All these new social media tools incentivise us to play with how we present ourselves to extents never before seen.

It’s easy to fall down a rabbit hole. Tavi Gevinson—actress, writer, and former editor of Rookie—once wrote, of her Instagram persona, “When I review posts, I almost envy my own life as though it were someone else’s.”

There is a paradoxical tension in online self-presentation that leads to contradictory forces acting upon users. On one side, you experience the rigidity of photographic constraints by having to select a single moment, a single profile. By doing so, you edit out the complexity and richness of vocal timbre, body fragrance, the angles of shadows on a face, gestures, the grammar of the eyes....

This applies to video too. But you also deal with the numerous possibilities this allows. You can now subtract yourself from the triviality of humankind: Yawns, double chins, snorts, greasy hair. What impact does this have?

Increasingly, tools for sharing and editing selfies are also linked to incidences of narcissism and body dysmorphia.

AK: When we think about the disembodied nature of digital selfhood, another factor that springs to mind is fraud. Performance of personhood in a platform economy entails a particular confluence of capital and power that, in some cases, reproduces existing relations of production and, in other cases, broadens them—democratises them, by some accounts.

The datafied self has a tangible value in a way that isn’t quite true of the analogue self, at least not in any general sense. The digital self is a particular mechanism and site for the production, extraction and consumption of value.

It has always been possible to extract value from others. This principle underpins many, if not all, economic systems. But in this case, digital transformation enables a facilitation of fraud in a manner and at a scale that is completely new. Virtual identity theft, data hacks, catfishing—all are the product of specifically digital ways of being. One result we see now is the collapsing together of discourses of cybersecurity and selfhood—where an acceptable self is claimed to be, to a large extent, a securitised self.

The thing is, positions on the securitisation of digital selfhood can differ depending on someone’s generation or background.

Where do we go from here?

NB: How we define ourselves, online or not, is constantly challenged by new tools and customs. The only constant is that it constantly evolves. Apps like BeReal, or organisations like the Center for Humane Technology, may provide clues to what a current margin of individuals will develop in the near future.

BeReal claims to be “a new and unique way to discover who your friends really are in their daily life.” It messages people and their friends at random times of day, then gives them two minutes to take a photo and selfie simultaneously—no filters, no editing, no deleting.

At the Center for Humane Tech, co-founder Tristan Harris, a former design ethicist at Google, wants to create apps and online spaces that consume less attention and time, and will ostensibly be healthier for people.

Since we now know that social networks are designed to produce specific effects (keeping us connected, and consuming content, as long as possible), we might turn to online spaces that are more attention and identity friendly. People’s desire to navigate cyberspaces where they feel less judged, or less pushed to “promote” themselves “coherently,” might incentivise companies to create networks suited to those needs.

AK: Even if BeReal struggles to gain footing among a significant number of users, it can still point us toward attitudinal currents surrounding digital selfhood. People’s dwindling patience for online posturing might impact how platforms manage digital self-presentation.

Posturing has a relationship to misinformation. The discourses that exist around its associated risks have future implications for how people view and interpret practices of online self-presentation.

The shifts we see taking place in how Facebook, for example, orients towards the pluralities of self that digital technologies enable (like Instagram suggesting multiple profiles for different purposes) signals a shift in how advertising infrastructures intersect and interact with online self-presentation.

To me this reveals not only an adaptation by platforms to user practices, but an adaptation to the complexity and plurality of digital personhood. This can get chicken-and-egg: Are platforms adapting to practices of digital selfhood, or driving them?

As with most things, it’s likely to be a bit from column A, and a bit from column B.

NB: As a digital anthropologist, rather well-informed about the vices and deceptions of online presentation of self, now I wonder, “What will my online self be like in years to come?”

I’ve been thinking about what will happen with all our online data—and online selves—when we have children, when we grow old, and when we die. Will I share my Snapchat stories or Instagram feed with my kids? In 10-20 years’ time, will I be watching my past Instagram stories under the heading “17 years ago, you posted this”? Or will we, as older millennial/Gen-Z adults, struggle to hide our Instagram or TikTok feeds from our kids? (This situation actually inspired a series of memes—”Honey, I found a picture of your grandma/grandpa”).

Will our kids fight over deceased parents’ data for safe storage after death, like family heirlooms?

We tend to forget that we will grow old while our online data remains untouched. A 2019 Oxford study found that Facebook could have as many dead members as living ones by the end of the century. It wouldn’t be surprising if, in the decades to come, we witness a growing number of companies offering to clean, curate, delete and store our social media content, during our lifetimes and after we are gone.

I don’t personally know what I will be willing to keep online, delete or share with my descendants, or if I should invest in a social media curating company. But I guess that’s a question we will all have to face eventually. Curating our digital legacy, as well as our online selves, will likely become routine.

AK: When we try thinking about future trajectories of digital selfhood, one term that springs to mind is transhumanism—the enhancement of human emotive, cognitive and physical capabilities through technology. In one of its stricter iterations, this philosophy extends to a truly posthuman vision, where we join with technology in a kind of singularity.

This seems far-fetched for now. But in reality, practices are already moving in this direction, with increasing merging of the virtual and the actual.

When we think about the rules that define how we are expected to appear in different online environments, what we see is far from monolithic. This makes digital self-determination a complex, sometimes risky endeavour. But the capacity to self-determine is nevertheless a profound objective.

One focus of recent digital literacy discourse has been the challenge of dealing with misinformation. But an equally pressing area of concern might be to ensure the capacity to engage in self-reflexivity around practices of digital self-presentation. For now, capabilities in this area remain underdeveloped. It is not just automated models for analysing sentiment that struggle to identify irony and the effects of context dependence.

We have to think about the kinds of signals people are assessing. What do people actually surmise from a like or retweet? Do these actions have inherent meaning? Is a like or retweet an endorsement?

Judgments made around what we do online is something I personally contended with when, while writing my PhD on online support for Donald Trump’s candidacy in 2016, I fielded questions from concerned connections, who wanted me to explain why I “liked” Trump’s Facebook page.

I had slammed into an unwritten rule. Patrolling its application was in this case facilitated by digital systems. But people also possess an awareness of these rules and frequently engage in discussions about how they impact community standards.

Anyone who studies these spaces—not to mention those building, managing or otherwise profiting from them—must be attuned to the emergence and development of different systems for regulating multiplicity, promoting notions of personal coherence, and inculcating strategies of personal branding.

12 Aug 2021

-

L'Atelier's Digital Anthropology Stream

Illustrations by Dominika Haas.

DATA-DRIVEN TECH & SOCIAL TRENDS. DISCOVERED WEEKLY. DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX.

02/03

Related Insights

03/03

L’Atelier is a data intelligence company based in Paris.

We use advanced machine learning and generative AI to identify emerging technologies and analyse their impact on countries, companies, and capital.