A primer on the Metaverse (and whether Fortnite counts as one)

Fortnite is “a phenomenon that transcends gaming,” said Epic CEO Tim Sweeney at the start of the company’s much-publicised trial against Apple in May 2021.

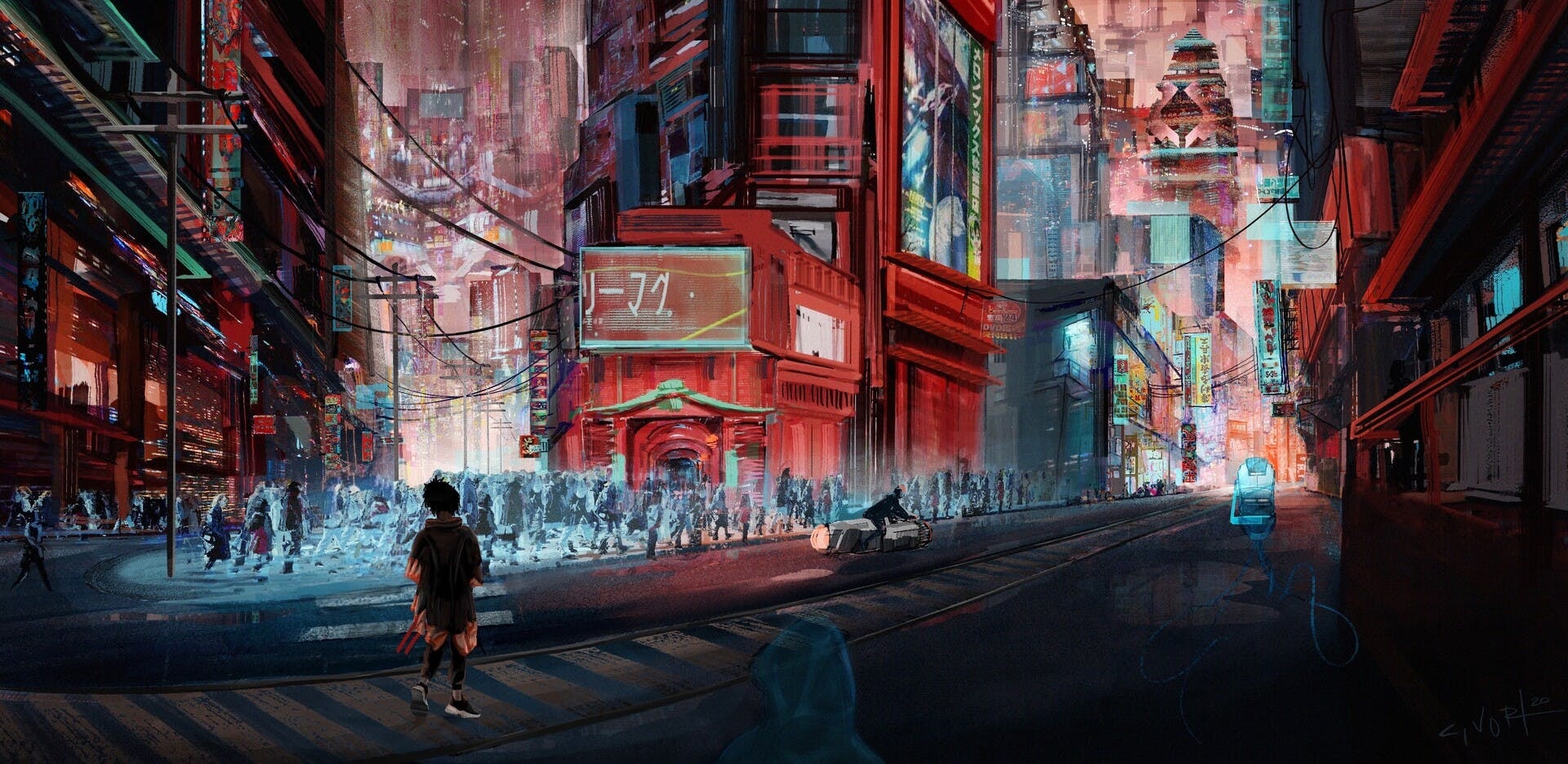

He then launched into a description of “metaverse,” drawing from Neal Stephenson’s 1992 cyberpunk novel Snow Crash—“a real-time, computer-powered 3D entertainment and social medium in which real people would go into a 3D simulation together and have experiences of all sorts.” In his view, the description fit Epic’s Fortnite: Not a video game, but a shared social experience in a virtual world. A metaverse.

Before getting to whether Fortnite counts as one, let's address a more pressing question—what is a metaverse?

The metaverse in fiction

"Hiro’s not actually here at all. He’s in a computer-generated universe that his computer is drawing onto his goggles and pumping into his earphones. In the lingo, this imaginary place is known as the Metaverse. Hiro spends a lot of time in the Metaverse.”—Neal Stephenson, Snow Crash.

The term “metaverse” first appeared in Snow Crash, where it describes a virtual online world where users exist as avatars. "Meta”—meaning “beyond” or “transcending”—is key. The metaverse is a universe beyond “real life,” a virtual expanse outside the confines of the everyday. And in the novel, it’s where the main character Hiro can own a luxurious mansion, whereas he actually lives in little more than a converted shipping container.

Though Stephenson coined the term, the idea of a virtual online world goes back further in science fiction. William Gibson wrote about cyberspace, a similar concept, as far back as 1982 in the short story “Burning Chrome.” He expanded on this idea in the 1984 novel Neuromancer, describing cyberspace as a “consensual hallucination experienced daily” and a “graphic representation of data abstracted from the banks of every computer in the human system.”

“Cyberspace” has come to be associated with what we now call the World Wide Web. But the metaverse has been adopted as a buzzword that symbolises the next generation of our hyperconnected reality. Rather than navigating through static social media sites and online storefronts, tech evangelists claim we will all be exploring and socialising within a virtual world.

In Snow Crash, the metaverse is a virtual globe, somewhat bigger than planet Earth. This globe is ringed by the Street, which constitutes the main hub of activity. It offers familiar real-world representations of things like buildings and parks, but also “things that do not exist in Reality, such as vast hovering overhead light shows, special neighbourhoods where the rules of three-dimensional spacetime are ignored, and free-combat zones where people can go to hunt and kill each other.”

Users access the metaverse through laser beams projected onto their eyeballs, which provide a realistic 3D representation of this other world. And its virtual real estate is for sale, with companies paying the Global Multimedia Protocol Group—which runs the metaverse—to build shops, offices and entertainment facilities along the Street.

Other authors have since built on the metaverse idea, notably Ernest Cline in his 2011 novel Ready Player One, which became a film by Steven Spielberg in 2018. In Cline’s work, users access the metaverse—a virtual universe dubbed OASIS—through sophisticated virtual reality setups. Pop culture reigns supreme, with avatars flitting around in ships and cars from Star Wars, Back to the Future, and dozens of other franchises in something of a copyright lawyer’s nightmare.

Fan art of Hiro within Snow Crash's metaverse, illustrated by Victor Gil.

Bringing the metaverse to our world

The notion of the metaverse has fuelled the imaginations of tech nerds up and down Silicon Valley, and there have been several attempts to make it a reality. The most famous is Second Life, a grand attempt to build a virtual universe where people can socialise, shop, buy a house, and even make a living.

San Francisco-based developer Linden Lab launched Second Life in 2003, and its sheer novelty quickly attracted headlines. Massively multiplayer online role-playing games were gaining in popularity at the time—World of Warcraft launched the following year—but Second Life wasn’t a game; it was a place to exist in. It was unlike anything anyone had ever experienced before.

Intriguing, even absurd stories emerged from this metaverse. The Maldives opened an embassy there. IBM bought ten islands for employees to meet and socialise on. U2 played a virtual concert. The user Anshe Chung became a millionaire selling virtual real estate, and others began making a living by creating and selling virtual items.

Inevitably, there were problems, as one expects when hundreds of thousands of people share space. One avatar memorably made a nuisance by flooding the world with political billboards, and the practice of “breaking and fornicating” became an irritating issue.

Despite the attention it received, Second Life never quite penetrated the mainstream. It enjoyed about one million monthly active users in 2013, a figure that fell to between 800.000 and 900.000 in 2017. (Today, thanks in part to NFTs, its virtual economy is thriving, however—last year, its players cashed out $73M, one-fifth more than 2019's $65M.)

By contrast, Fortnite had roughly 30 million monthly active users in 2020. But is Fortnite really a metaverse?

Second Life in the Covid-19 age, courtesy of Quartz.

Fortnite on trial

The Epic vs Apple trial in May 2021 was triggered when the ability to buy in-game currency—V-Bucks—directly from Epic was introduced in the iOS version of Fortnite. This meant Apple would not receive its 30 percent commission. Since the move violated the latter’s terms of service, it de-listed Fortnite from the App Store. But the transgression was a calculated move on Epic’s part: It launched an antitrust lawsuit, complaining about the 30 percent commission and the inability to take direct payments.

Epic’s opening statement in the trial included a slideshow that unambiguously presents Fortnite as a metaverse. Its goal was to express Fortnite’s long-term goal to become “a platform for creators to distribute their work to users," and demonstrate that Apple’s 30 percent commission stifles the development of this metaverse.

“With Apple taking 30 percent off of the top, it makes it very hard for Epic and creators to exist in this future world,” Sweeney argued.

Suddenly, Fortnite’s potential role as a metaverse, not merely a video game, became an important legal issue—even if it wasn’t the crux of Epic’s case. There is certainly evidence that Fortnite is more than a game: It became a social meeting place for many groups of friends, particularly younger people, and particularly during the coronavirus pandemic. Numerous non-gaming activities have certainly taken place there: Concerts by the likes of Travis Scott, Marshmello and Ariana Grande; and a trailer for The Rise of Skywalker debuted at a special Star Wars event.

Since April 2020, Fortnite’s conflict-free Party Royale mode (as opposed to its Battle Royale gaming mode) provides dedicated space for social meetups, where it’s screened Christopher Nolan films for gathered avatars to watch. Meanwhile, its creative mode lets players make their own islands to share with others.

But does this make it a metaverse? There are impassioned arguments about whether Second Life constituted one. Compared with Fortnite, it fits the bill more precisely: Second Life users can create pretty much anything they like across a vast in-game world—a scenario closer to the metaverse depicted in Snow Crash. By contrast, Fortnite is limited in what it can offer.

Ultimately, it comes down to how narrowly one defines a metaverse.

Marshmellow "live" in Fortnite, 2019.

Defining "metaverse" for the virtual present (and future)

If we define it as a virtual space where avatars can meet, pretty much every online first-person shooter and role-playing game would qualify. But if we define it as a place where avatars can meet and do something besides play a game, then yes, Fortnite is a metaverse. Just about. (Second Life players are likely to disagree.)

Crucially, investors believe in Sweeney’s long held-dream of building a metaverse. It’s a topic he brings up again and again in interviews, and companies are betting big on his vision.

Lego Ventures, the investment arm of the toy brand, has backed it. “We see Fortnite taking a pretty good stab at making the first credible metaverse, where people can play and watch and share and socialise together,” said Rob Lowe from Lego Ventures. And Epic raised $1 billion in funding from a slew of investors—including Sony—in April 2021. “We are grateful to our new and existing investors who support our vision for Epic and the metaverse,” said Sweeney at the time.

One thing is clear: the actual metaverse won’t be anything like the one depicted in Snow Crash. For a start, there is unlikely to be just one. As with social media sites, different companies will present different metaverses, each with varying degrees of “metaversiness.” Some will succeed, some will fail, but ultimately we’re likely to end up with more than one, just as Twitter, Facebook, Instagram et al. compete for similar shares of the marketplace and of our time.

There’s the question of virtual reality. Sweeney might call Fortnite a metaverse, but the metaverses in Snow Crash and Ready Player One are fully-immersive virtual spaces that players experience in three dimensions.

“VR has the ability to take you to a completely different fictional place—the kind of thing that’s described in the Metaverse in Snow Crash. When you go into the Metaverse, you’re on the street, you’re in the Black Sun, and your surroundings disappear,” Neal Stephenson told Vanity Fair in 2017. We’re not quite at that stage.

Technical barriers to creating a VR metaverse are considerable, not least the sheer bandwidth required to allow a group of ultra-detailed avatars to meet and freely interact in a VR world. Then there is VR’s slow take-up: The global market is expected to be worth as much as $57,5B by 2027 ... but presently, only about 1,2 percent of households have a VR headset.

Linden Lab has worked on a metaverse-style VR concept called Sansar since 2016—one reviewer described it as "WordPress for social VR"—but gave up in 2020. Linden Lab sold Sansar to the startup Wookey Project Corp., saying it wanted to focus on Second Life, with CEO Ebbe Altberg admitting to Engadget that it entered VR “a bit early,” and that Sansar has “still [got] quite a way of runway [before it can] become a cash-positive.”

There remain plenty of competitors in the metaverse race. Facebook could be the one to watch. It bought VR firm Oculus in 2014, and is currently working on Facebook Horizon, “a social experience where you can explore, play and create in extraordinary ways.”

The service is in beta, and though it’s been touted as a first step toward a metaverse, Facebook avoids that label. “We always struggle with this one, because ‘metaverse’ means so many different things to different people, even internally,” said head of product marketing Meaghan Fitzgerald in an interview with VentureBeat. “We see it as an opportunity to encourage more social interaction in VR, to make social engagement in VR deeper and richer, to help people build their graph of friends to connect with.”

Then there’s Decentraland, a “virtual world owned by its users,” built on the blockchain. Its universe is designed around the cryptocurrency Ethereum, and NFTs (non-fungible tokens), which promise that users can unequivocally own the things they create and buy. In June 2021, historic auction house Sotheby’s unveiled a virtual gallery in Decentraland, and a patch of virtual land in the metaverse sold for over $900.000 that same month. Even VR support is promised down the line. But Decentraland, too, has a ways to go before catching up with Fortnite’s sheer popularity—it averaged 10.000 daily active users in March 2021.

Perhaps the problem with visions of the metaverse is that it’s not immediately obvious why one might want one (unless you’re a Silicon Valley evangelist). Fortnite attracted players with a brilliant, free-to-play video game, then incorporated metaverse aspects down the line: Players came for the Battle Royale, then stayed for free concerts and social gatherings; eventually, popping into Fortnite to “see” friends became second nature.

By contrast, the prospect of “owning” a slice of virgin virtual land, open to the imagination, might mystify most people, unless they’re early adopters.

Rather than as a revolution, perhaps the metaverse will arrive in dribs and drabs: A social space bolted onto Minecraft. An option to watch movies with friends in a virtual Facebook theatre. Tiny, discrete add-ons that gradually coalesce into something bigger.

But we should also remember the very reason citizens of Snow Crash and Ready Player One so readily embraced the metaverse. These stories are dystopian visions of the future, where the world outside is so stupendously awful, so corrupted by corporate oligarchies or catastrophic climate change, that retreating into a virtual world is perceived as sweet relief.

It may be the case that for a metaverse to truly succeed—and be fully embraced by billions across the globe—the real world has to fail.

06 Aug 2021

-

Lewis Packwood

DATA-DRIVEN TECH & SOCIAL TRENDS. DISCOVERED WEEKLY. DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX.

02/03

Related Insights

03/03

L’Atelier is a data intelligence company based in Paris.

We use advanced machine learning and generative AI to identify emerging technologies and analyse their impact on countries, companies, and capital.