Programming trust: Web3 could break programmatic ad tech's spell. Are we ready?

In the 90s dot-com era, behavioural scientist and lab administrator BJ Fogg published the first peer-reviewed article on Captology ethics—using computing technology to change attitudes or behaviours, a process known as persuasive computing. Captology refers to "persuasive technologies" at large.

In 2006, the lab released a video, shown below, designed to warn the Federal Trade Commission, policymakers, and the public about persuasive computing’s potential impacts: Websites that may exploit trust, psychological manipulation of users through Big Data, and persuasion profiling, or using algorithms to tailor messages based on past behaviour.

BJ Fogg describing persuasion profiling to the FTC, fall 2006.

By 2006, Facebook use was ubiquitous, with its optimistic tech narrative of connecting people. In 2012, the Arab Spring swept the Middle East; civil citizens used Facebook to organise protests that deposed Mubarak’s regime in Egypt, and corrupt leaders in Tunisia, Libya, and Yemen.

But Facebook’s algorithm has one job: To keep people on its website, interacting and sharing. Thus, emotionally triggering content receives higher visibility; with it, content that mongers fear or incites rage. This resulted in deadly clashes amongst divided factions, evidence of the platform’s destructive potential.

These same effects, paired with granular ad targeting, were put to use by the Internet Research Agency, a Russian content farm that leveraged knowledge of social media algorithms to spread disinformation during the 2016 United States presidential election.

According to the Global Disinformation Index, disinformation “occurs when someone pushes an intentionally misleading adversarial narrative against democratic institutions, scientific consensus or an at-risk group which carries a risk of harm and is often crafted using selected elements of fact.” The IRA had already worked, between 2013-2014, to undermine Ukraine’s democracy from within; it duplicated many tactics for the US in 2016.

Ads and Facebook groups micro-targeted American audiences using extreme political, racial, gendered, and religious narratives to fuel division. 150 million users joined polarised Facebook groups, created with false accounts. Hyperpartisan Facebook pages impersonated real people and social movements, culminating in crowd-drawing protest events like “March for Trump” and “Support Hillary. Save American Muslims.”

A Senate Committee intelligence report found Facebook (now Meta) discovered “approximately $100.000 in ad spending using targeting tools from June of 2015 to May of 2017 associated with roughly 3.000 ads connected to about 470 inauthentic accounts and pages in violation of Facebook’s policies.”

The world we’re in, the world ahead

Written 73 years ago, George Orwell’s 1984 topped Amazon’s bestseller list in 2021 and 2022, due in part to dystopian narratives advanced during the COVID-19 pandemic. While it’s natural to see parallels between current events and the novel, 1984 better reflects its World War II context than the 21st century’s particular travails. Researcher Zeynep Tafecki argues that our contemporary crisis revolves less around classic authoritarianism and more around an almost incidental kind, driven by strategic leveraging of our data within Web 2.0 platforms.

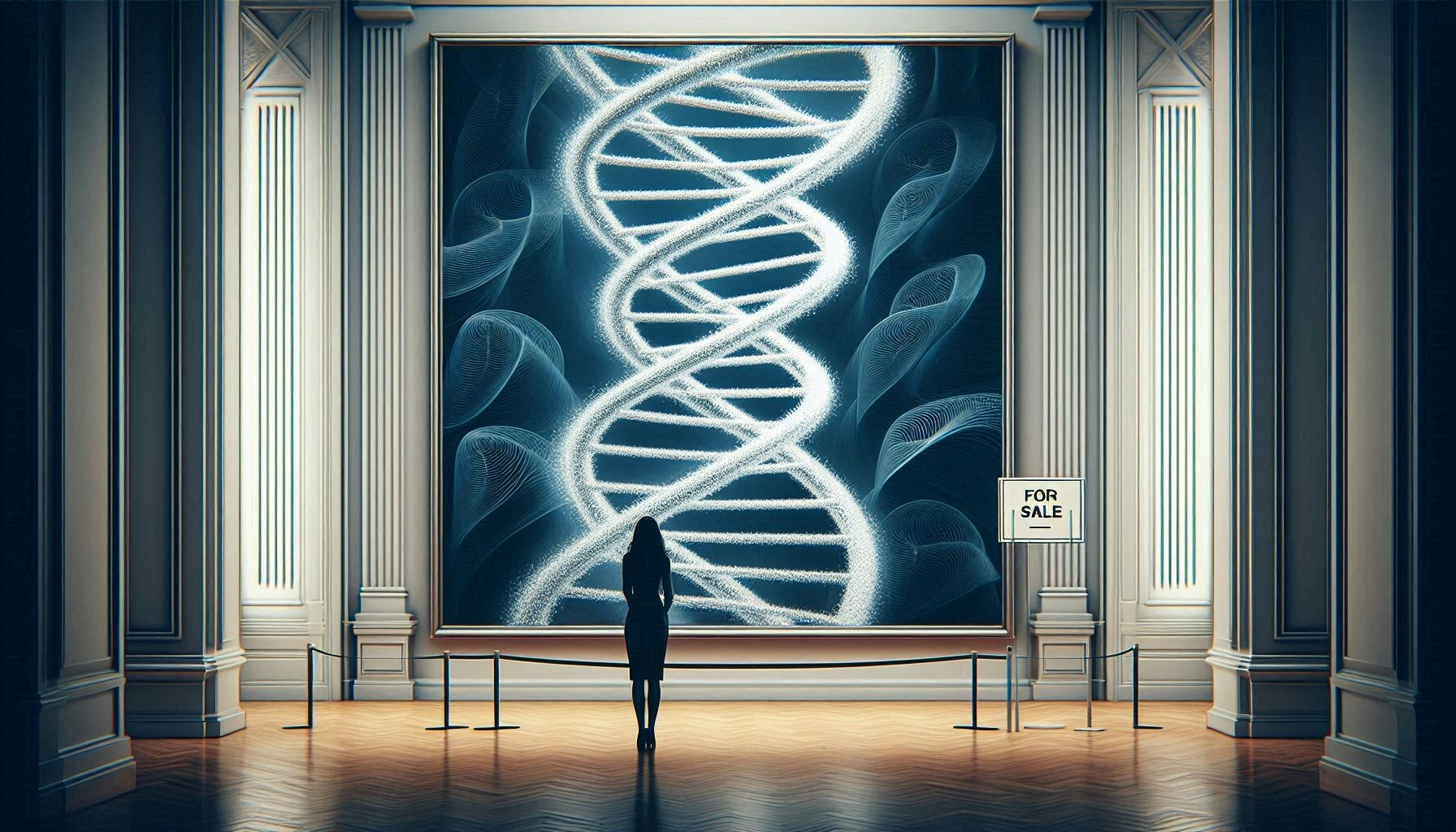

“Much of the technology that threatens our freedom and our dignity is being developed by companies in the business of capturing our data and selling it and our attention to advertisers,” Tafecki cautioned in a 2018 TED Talk. “We’re building an infrastructure of surveillance authoritarianism just to get people to click on ads. This is not Orwell’s 1984. This is the people in power using the algorithms to quietly judge us, to nudge us, and to predict and identify the troublemakers and the rebels, to deploy persuasion architectures at scale and to manipulate individuals.”

Ad tech disrupted democracy by allowing the Web 2.0 disinformation crisis to flourish, through exploited personal data surveillance gateways. In contrast, the coming Web3 promises decentralisation: No “owner” of a system can own or even interpret your data, so no single entity can bend it with intent.

Still, in Web3’s brave new world, attention flow will remain the highest commodity. Pioneers are rallying to develop programmatic solutions for “trust,” which eroded as Web 2.0 matured. If Web3 is characterised by blockchain technology and a further blurring of offline and online, Web 2.0 made its mark with social media. The latter is addictive, compelling us to bleed time, releasing more data as we go. This is what’s made our identities, preferences and movements so easy to track—and use.

By 2020, we grappled with the reality that the tech tools purporting to unite us can sow deep division, sometimes fueling genocides and massacres. In the Philippines, former President Rodrigo Duterte used paid followers and fake Facebook accounts to spread efficacy lies about his drug war policies and attack critics. Nobel prize-winning journalist Maria Ressa called this “patriotic trolling,” online state-sponsored hate speech designed to intimidate dissidents or critics. In Myanmar, hate speech about the Muslim minority appears on Facebook as memes and fake news; in Ethopia’s Tigray conflict, inflammatory content on Facebook and Twitter is boosted by algorithms.

Our personal data is used for many motives, including PSYOPS tactics: weapons-grade communication techniques intent on leveraging political narratives to alter behaviour at scale. This is facilitated by platforms that quantify interactions, likes, preferences, and activities so data brokers can pawn them to advertisers, resulting in what Harvard professor Shoshanna Zuboff refers to as “surveillance capitalism.”

The “Breitbart Doctrine”—the idea that, to change politics, you must first change culture—emerged in 2018, when Cambridge Analytica's data brokerage practices provided the best case study possible. Cambridge Analytica identified “swing” voters” who could, with the right content, be persuaded to choose a particular candidate, or suppress voter turnout. It was an approach the group first used in the developing world (comprehensively depicted in The Great Hack), then during the 2016 UK Brexit referendum and 2016 Trump campaign.

These effects and manipulations weren't passively received. A 2022 letter to YouTube’s CEO, signed by over 80 information integrity organisations from 40 countries, demanded significant platform reform, asserting YouTube “[allows] its platform to be weaponised by unscrupulous actors.” Tech companies were urged to make four major changes, including “funding research and algorithmic adjustments.”

Web 2.0’s ad conundrum

Clare Melford of the Global Disinformation Index says media buying practices, like the technology powering them, grew exponentially in the absence of market standards until the early 2000s, when buyers primarily controlled placements. Most digital ad technology has since pivoted to a programmatic approach, where third-party algorithms can place ads and A/B test variations efficiently across populations and at different times. This facilitates advertising that can rapidly scale. Today, advertisers may only see clicks and impression metrics in their reports … often, they no longer decide where their ads go.

“Online ads evolved into incredible behavioural modification tools because they can run A/B tests in the moment,” says Melford. “Advertisers quickly home in on how to present information for users in ways that get them to act. We are no longer buying ad placement, rather people’s clicks. We created an entire ecosystem because of the engagement model that rewards sensational behavior where outrage equals clicks.”

The global ad tech system includes thousands of corporations and ad networks, which Google calls “authorised buyers.” These function like data supply chains flowing through Google business tools. The latter efficiently traffics online ads, intermediary businesses, and signed contracts—culminating in the bid stream, like an RSS feed for advertising. This is how large companies typically get user data now, and where most data vulnerabilities can occur, per Zach Edwards of Victory Medium, an ad tech consultancy firm.

“Most companies target the broad internet to optimise client ad budgets. There are gaps in accountability to the point where clients like major corporations often don't know what type of content they’re funding,” says Edwards.

In open internet ad buying, a brand or business gives a broker a budget. The broker places ads on websites that reflect terms like “politics” or “economics.” Human brokers can't reasonably review tens of millions of potential websites; instead, they review clusters whose content matches categories of interest. The site where an ad is placed could be hyper-relevant. Alternatively, the ad could end up on an ad farm—a site that clocks high traffic for certain keywords to draw ads, which are then clicked on by bots, not people. In the least pleasant cases, a placement between ad and content could be horribly ironic or tragic.

Brokers overcorrected this placement problem by blocking terms deemed threatening, which inadvertently led to excluding ads pertinent to certain minority groups, rendering content or journalism about them less profitable and therefore less likely to be funded, reducing coverage. Social media ad tools also enable advertisers to exclude certain groups (women and minorities) from ad targeting; in 2019, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development sued Facebook for housing discrimination via targeted ads, violating the Fair Housing Act. Finding data brokers remains difficult; they are represented by a confusing array of shell companies. Vermont and California enacted the first laws for creating data broker registries in 2018.

On 24 January, the US Department of Justice and several state attorneys general filed a civil antitrust suit against Google, alleging it monopolises the “ad tech stack”—digital advertising technologies where publishers sell ad space and advertisers buy it. The suit is under Sections 1 and 2 of the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, and follows a 2020 case where the Justice Department alleged Google monopolised search advertising and the search industry overall. These suits represent major milestones towards ad tech regulation in the United States.

Opt-out options and public outcry

Experts say design ethics and regulation are key to curbing disinformation. Melford predicts things will get worse before they get better.

“We are dealing with technologies that can manipulate us in ways that we don’t understand,” she said. “We could see significantly more civil unrest and backsliding of democracy. We must make the technology more accountable. Ethics need to be built in by design. There needs to also be a larger public outcry about wholesale data harvesting.”

Governments are taking strides to address ad-funded disinformation, and introduced a panoply of legislative proposals retroactively. In the European Union, the Digital Services Act and Digital Markets Act were adopted by the Council of the European Union, signed by the Presidents of both institutions and published in the Official Journal. Their goal is to create a single set of EU rules to create safer spaces for users and establish a level playing field for innovation. The DSA holds platforms accountable for better content moderation, including mitigating disinformation, terrorist content, and explicit content, with Article 36 demanding codes of conduct for online advertising.

After the DSA’s passage in November 2022, online platforms were required to publish their active European user counts by 17 February 2023. Several tech giants, including Amazon, Apple, and Pinterest, failed to.

The 2022 Online Safety Bill proposed by UK Parliament gives British regulator Ofcom sweeping authority over internet firms, with the power to fine non-compliant companies up to 10 percent of annual global turnover, block non-compliant sites, and make them improve practices. In January 2023, the House of Commons passed the bill to the House of Lords. It must pass both houses of Parliament to take effect. A timeframe for enforcement is currently unknown.

The United States, the predominant source of unchecked Big Tech, has seen the most proposals. These include the Banning Surveillance Advertising Act of 2022, which seeks to restrict targeted advertising practices by prohibiting ad tech companies from using personal information to target ads by race, gender, and religion. Since 2020, nearly 40 legislative reform proposals called to reexamine Section 230, a debated provision of the Communications Decency Act that frees platform owners from third-party content liability.

Brands introduced advertising and publishing policies to restrict which ads can run on their networks, but they’re often inconsistent and unenforced. Perhaps reform lies within the tech itself? The RAND Corporation compiled a list of disinformation-fighting tools, including ad blockers and trollbot trackers. In March 2022, Google added fact-checking notices to news stories, including a “highly-cited” label.

Web3 tokenomics, and programming trust

Web 2.0 ad tech has myriad transparency issues, including unreliable data, since third-party ad services use proprietary bid stream interactions and metrics. The blockchain is more transparent, eliminating the need for third parties, but its technology is still too young to replace Web 2.0 methods at scale.

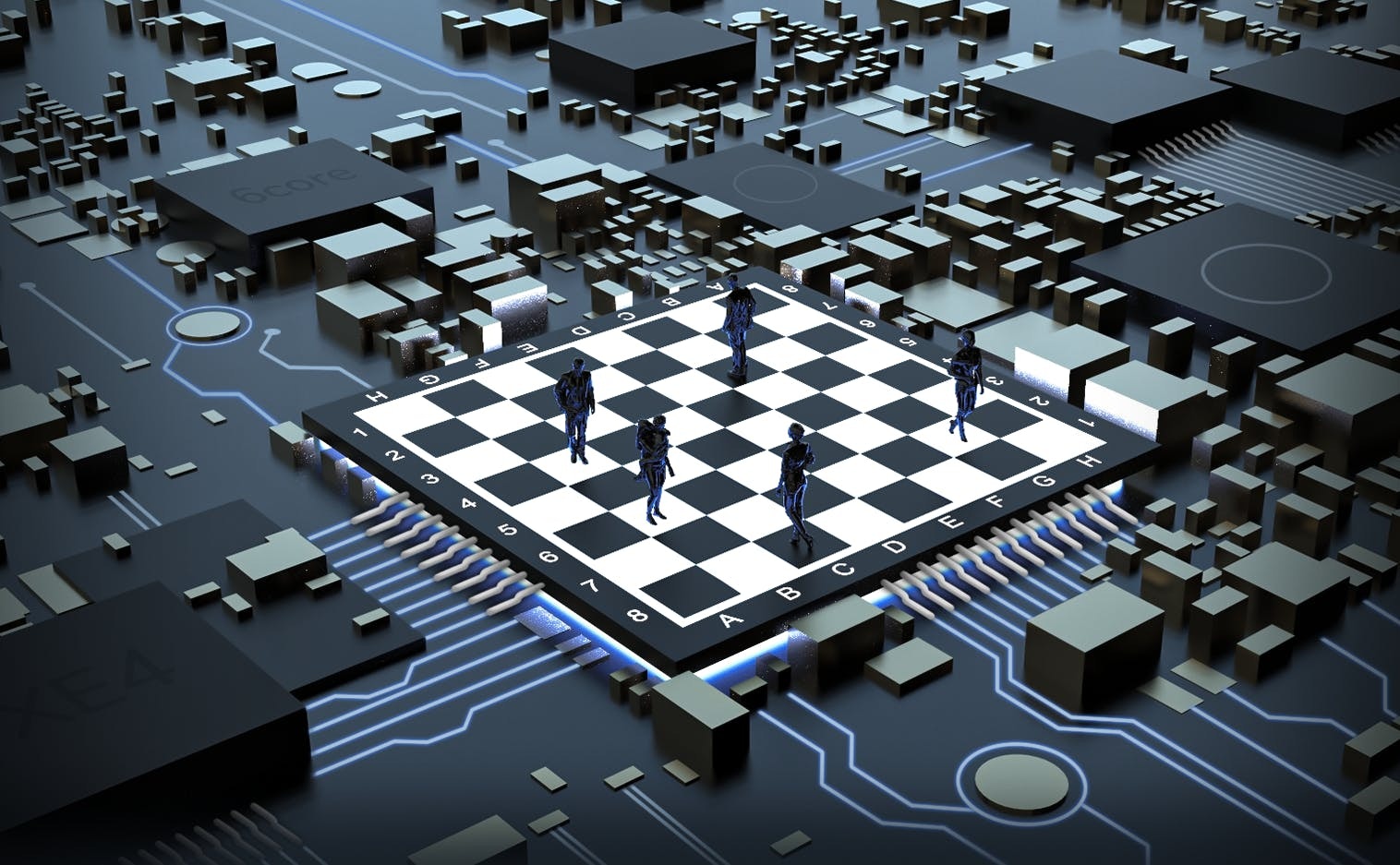

But in Web3, trust can be programmed. Game theory and token-driven economics—tokenomics, coined in 1972 by Harvard psychologist BF Skinner—can shape behaviour in a system. This approach informs cryptocurrency and Web3 overall, theoretically incentivising good actors and deterring bad ones. For example, helping create crypto assets—and receiving crypto without buying it—is tied to acts that benefit the blockchain community.

"Web3 is a bottom-up environment where users have control over their data and identity, unlike Web2 where monolithic corporations use it for profit," says Nadja Bester, co-founder of AdLunam, Inc.

Web3’s takeoff will change how money flows. Bester’s Initial Dex Offering (IDO) launchpad is designed around a proof of attention allocation model. In crypto’s early days, overpromoted Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs)—a way for young cryptocurrencies to raise money and visibility—wrought bubble-caliber investments and scandal. Competition gets fierce for investing in tokens after private rounds. An offering or “allocation” period starts a feeding frenzy, with public investors cramming to get into public funding rounds.

Sidestepping that (and inflated valuations), in a proof of attention model, investors participate in launchpad token staking, where they lock certain numbers of tokens bought or accumulated, or that were issued to them by the launchpad, to receive guaranteed participation in the sale. Bester’s launchpad calls itself a community, where users engage around investments while earning community badges and rankings towards an attention score for allocation eligibility, kind of like Reddit.

In other words, to receive allocations, the community has to vouch for your past contributions and behaviour. Take this concept and apply it to online advertising, and you have Presearch, which includes a decentralised community-powered search engine. Presearch provides participation awards, and a search alternative to data-gathering corporations like Google and Bing.

CEO Colin Pape founded Presearch after being “unfairly penalised by Google for a former business.” Upon discovering Ethereum in 2017, he saw the potential to create an ecosystem with a value exchange token advertisers could presell as advertising credits. Presearch leverages “keyword staking,” where advertisers receive PRE tokens to bid on certain keywords to get ads displayed. For advertisers, keywords represent transactional intent that signal existing consumer desires. The ecosystem rewards everyone for active participation while deterring abusive practices.

“One entity can’t be the complete arbiter of truth or democratic opinion won’t surface. Technology is not unbiased and this can be explained by the Web 2.0 filter bubbles created with our information,” says Pape. “People who use us want an alternative that supports privacy and decentralisation. This is an opportunity for advertisers to get into the Web3 space and connect to users who have aligned values.”

His vision is idealistic yet practical: To focus more on ad keywords to monetise flows of behaviour among anonymised users, instead of leveraging hyper-granular profiling like today’s tech companies. On Presearch, advertisers are rewarded for targeting users. Presearch ranks ads based on the quantity of pre-staked tokens, which Pape hopes to evolve into a trust-type score and denominated community value mechanism … eventually culminating in users building bespoke curated search engines that resonate with their values, not unseen intents.

Have we learned sufficiently from the sins of Web 2.0? While decentralisation is all the rage, Web3 is clunky and nascent, leaving enthusiasts speculating whether the blockchain and tokenomics offer viable mainstream solutions. To date, cryptocurrency valuations are largely driven by hype, like investments in Silicon Valley startups (such as Theranos).

“Blockchain has latency issues,” says Bester, “whereas ad tech transactions happen in milliseconds. The speed of blockchain transactions do not yet fully rival them. However, despite being absent a playbook, projects are fast-moving and building on the shoulders of predecessors, allowing unintended consequences to be mitigated.”

There is the matter of user responsibility, which Web 2.0 platforms shirked. The latter gave us interfaces so user-friendly they practically became second nature, further facilitating mass manipulation. (Facebook Business’s ad platform made deeply granular targeting just as easy, building on years of parsed data about people’s spending habits, likes and dislikes, organisational affiliations, relationships, and more.)

In a decentralised technology space, users have to put their grown-up pants on. Imagine a world where you use a digital wallet to log onto services, instead of a standardised Web 2.0 login (“sign in with Google,” for example). Your information is safer, your privacy protected. But as dependence on digital wallets grows, losing wallet keys—or having them stolen—could become more consequential. You could be blocked from accessing your cryptocurrency, plane tickets, or membership cards to certain services. There isn’t often customer service to remedy these issues, which will grow more prevalent as Web3 technology scales into the hands of less sophisticated internet users.

After rolling out user-operated nodes—software that runs on a distributed network of computers, to process user search requests—to bring more power to the community, Pape admits total decentralisation of Presearch will take time to achieve. It will require a passionate, responsible community that takes ownership of their stakes, contributions, and research. They must also be willing to act as arbiters when necessary.

“My fear is turning back into a Web 2.0 or Wall Street environment because people don't want that level of responsibility for what they use,” says Pape. “They don’t realise that to truly hold the power, they have to take ownership for many things they may not want to.”

It’s hard to know whether Web3 “trust-building” methods, like keyword staking and proof of attention, will stand the test of time. For now, they offer a fresh perspective on how to get out of this dizzying maze of third-parties.

Intentionally or not, Web 2.0’s vanguards made ad tech a hazard zone for personal privacy and democracy. While Web3’s ultimate contribution remains theoretical, at least ethical questions are being considered at the start, not the end. Certain priorities—click-throughs, views, repeat interactions—were etched into the Web 2.0 advertising ecosystem. More thoughtful programming in Web3, rewarding community cohesion and robustness, could change not only behaviour, but what we expect from technology and each other.

New terms of engagement could mean a new social contract. But as Pape observes, the question remains whether we as users can meet the responsibilities implied therein.

18 May 2023

-

Jessica Buchleitner

Illustration by Dominika Haas.

02/03

Related Insights

03/03

L’Atelier is a data intelligence company based in Paris.

We use advanced machine learning and generative AI to identify emerging technologies and analyse their impact on countries, companies, and capital.