Cloud nationalism, multiplayer mercenaries and crypto wars: In Web3, we'll take our borders with us

When I submitted my PhD on nationalism for publication in 2012, a reviewer said it was not worth adding more ink to this dead subject. Doing so would be "giving credence" to a failed, dangerous ideology.

In the internet's early days, many expected national sentiment to wane into the 21st century, facilitated by this inherently non-territorial technology ... particularly in smaller or less-developed nations.

Nothing was further from the truth. A 2000 Halavais study showed how persistent national borders are, maybe because their reinforcement flies under our radars. To wit: The majority of websites in the United States link to other US-based sources.

Decades into the new millennium, nationalism remains rampant in daily life—including online. We may have thought the virtual world would be neutral and borderless, but it is rife with nationalist conflicts that reflect real-world happenings.

Pay-to-play patriots

“Putin is a loser.”

This is what my friend’s 8-year-old son says when meeting Russian players virtually on Roblox—an online space where people can make or play others' games—before telling them about the war in Ukraine. Through digital technology, political identities can clash (and thus reinforce themselves) in surprising new ways; that my friend’s circle saw it as evidence of good parenting strengthens the point.

Any medium that allows users to generate content is prone to becoming politicised; Roblox is no different. Things get interesting when national identity is at stake. Historically, nations were the vehicles that mobilised societies to action—whether for good or bad. They are among the few communities many of us are willing, or asked, to die for. Online games have become an unwitting arena for that combat.

According to The Economist, at one point China's state security services offered awards of up to 500.000 yuan to users reporting “agents of a foreign power.” As a result, China-based users began referring to individuals or companies, who published content perceived as unpatriotic, as “a walking 500.000” (yuan). Meanwhile, Chinese media showered praise on the "Red Army," a group in various multiplayer games that killed other characters unless they said “China number one.”

Narratives are always of interest to those seeking to galvanise a community. As a result, history curricula are organised in a way that gives nations a first-person perspective—“we” fought the invaders in the 12th century, even if the events took place before the development of national consciousness.

Many such efforts focus on equipping the modern national community with a sense of ancient lineage in addition to historical depth. Increasingly, this ideological work is done online: NagaRaja is a play-to-earn game that recreates ancient Indonesian (Nusantara) culture, with a player/member community motivated to explore a common past.

Nationalist online games are prime examples of a bottom-up movement—though their popularity tends to be temporary, and linked to particular events. Take the Resistance War Online, which celebrated China's victory over Japan; or the Aftermath VR game, which documented the events of Euromaidan in Ukraine.

The future of national memory is virtual

Beyond online games, other emerging spaces mirror national identity reinforcers in the “real” world.

The museum is the ultimate institution of national memory formation. Its galleries are the window into a nation’s soul. There is a reason each state has a network of national museums and galleries … and it isn’t related to funding.

In the aftermath of Apartheid, when the South African government had to unite its ethnically diverse population, museums became critical for shaping common identity. They presented a single narrative on slavery, and made a connection between the current people of South Africa and its indigenous inhabitants.

In Poland, the current right-wing government opened a museum of the Warsaw Uprising, an immersive exhibition that makes visitors feel they have to duck German bombs (the sound of which accompanies you almost constantly). In the 1990s, such an institution would have been considered too divisive—particularly given Polish strife related to joining the EU, and attempts to form positive relations with Germany.

More recently, the Ukrainian Ministry of Digital Transformation created an NFT museum of Russia’s invasion, the Meta History: Museum of War. The centrepiece is the “warline,” a day-by-day timeline of Ukrainian defensive efforts, with an NFT corresponding to each day.

NFT for day 187 of Ukraine's warline, emphasising President Volodymyr Zelenskyi's conviction that "the myth of Russia's greatness has been debunked." It includes a featured tweet from @KyivIndependent, with art by Olena Staranchuk. On sale for 0,3 ETH.

“Blockchain and NFT are the tools that work to preserve the statehood and history of Ukraine.” —Alex Bornyakov, Ukraine’s Deputy Minister of Digital Transformation.

The quote above comes from Bornyakov's Twitter post announcing the museum’s launch. One attraction of placing the artwork on the blockchain is the ability to control the historical account of the war, central to Ukraine's narrative of autonomous identity. A statement on the museum’s website reads:

“In Argentina, there's the Cave of the Hands—a nearly 10.000 years old site, where our ancestors left prints of their hands on the stone walls. By pure luck, this mind-altering art piece was preserved until our time. At MetaHistory, we don't want to leave it to luck. We aim to preserve the artworks of the war in Ukraine and beyond—immutable, on the blockchain, forever, for the future generations.”

The choice to build an NFT platform was not accidental. It presented a way for people to support the defence effort through NFT art purchases, in addition to direct crypto donations, which together topped $45M in July 2022, per a Twitter post on the museum’s official page. The NFT art collection accounted for $1M.

The frontline role of cryptocurrency and NFTs in this conflict inspired commentators to label the invasion of Ukraine “the world’s first crypto war.” Of course, political art, including NFT art, is nothing new. Kevin Abosch became famous for embedding information about state-run Uyghur concentration camps in an NFT, which is now on display in the national museum in China.

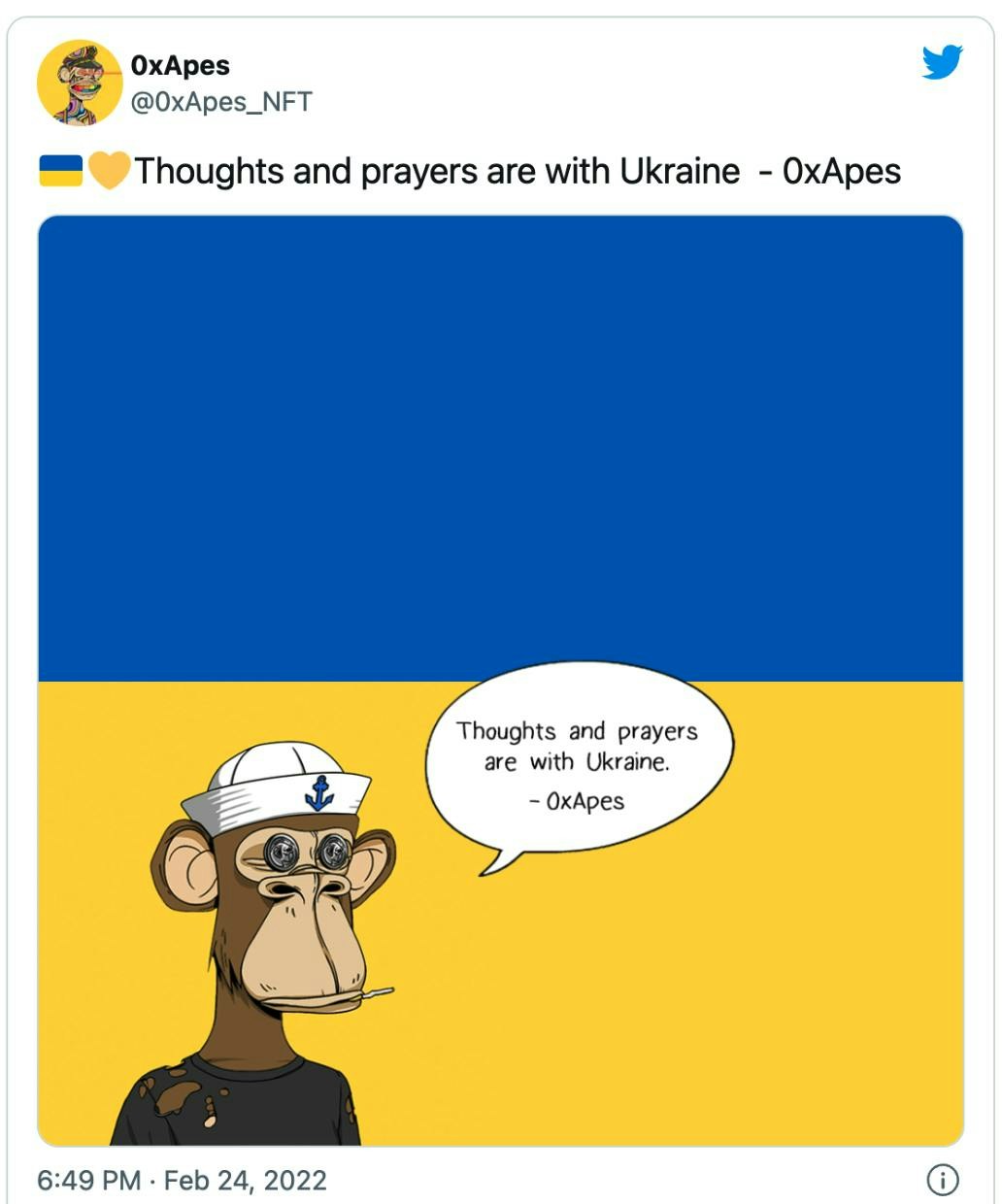

Similarly, NFTs helped mobilise global support around Ukraine’s pleas for help, including one from 0xApes:

Equally interesting is the #putin tag on the Web3 NFT platform Foundation. This may represent the first time the crypto community has organised itself to this extent around a political cause.

Other, more ambitious, projects appear less realistic. These include the New Ukraine Coin (website now unavailable), a Web3 project where participants could help design a digital twin of a proposed new city in Ukraine, where those fleeing the conflict could relocate after the war. The project did not appear to be endorsed by, or affiliated with, official Ukrainian state institutions, casting doubt on its viability. But it signals how decentralised communities can build their own national narratives through digital technologies.

Online, borders they don't blur; they bleed

It would be a mistake to equate online nationalism with conflicting identities or outbursts of national pride. Put simply, online nationalism is a set of processes by which national identity can be shaped and mobilised in online and virtual worlds.

Benedict Anderson famously called nations “imagined communities,” referring to how the sense of national identity was cultivated by print and the emergence of shared social consciousness. Alongside broadening public education, newspapers and books allowed us to imagine fellow nationals as “closer” to us than those lacking our same national consciousness.

In this broader sense, nationalism is an experience of the world that is fragmented by national borders. We rarely see it in everyday life unless we encounter some jarring form of difference. If you teleport from a bookstore in London to one in Lisbon or Paris, you may immediately notice the contrast in what books are promoted for reading, and how shelves are organised to facilitate a certain logic of what types of books matter more.

These subtle forms of everyday nationalism translate into how virtual spaces are organised, and what is perceived as truth. It informs conflicts that relate to nationalism in the narrow sense. Digital brands have sometimes unwittingly clashed with national experiences of different countries: Consider Google’s quandary on how to display languages or territories on their maps, or discussions between Roblox Nations users about whether Crimea should be depicted as Ukrainian or Russian.

If everyday experience is routinely national, it is only natural that the internet reproduces this.

Yet the architecture of the internet is not spontaneously nationalistic. For instance, the Turkish telecommunications regulator ruled in 2011 that certain words could not be used by websites with the .tr domain. These included phrases like “gay,” “lesbian” or “bisexual”—eliminating all Turkish LGBT sites from localised domain architecture.

The national architecture of internet ecosystems may feel natural, but in many ways lacks sense. Why, for instance, would Netflix filter content based on national preferences, instead of offering a truly personalised selection? That I am Polish does not negate the fact I may have a particular love for anime.

Further complicating this image is the degree to which the internet’s current global infrastructure depends on the “Big 5” (Amazon, Alphabet, Apple, Meta and Microsoft), who happen to be US-based. Until the mid-2010s, this did not seem to bother many people. On the contrary, many hoped the Chinese economy in particular would eventually open to Western technology companies. German and British governments even encouraged Chinese investment in critical infrastructure and technology in Europe, partly in hopes for reciprocity.

But breaks on global foreign direct investment were pulled way before the war in Ukraine, increasing concerns about ownership of technology and security. China’s refusal to “open,” and subsequent success developing its own digital infrastructure, led to a wave of “cloud nationalism,” where US and Chinese regulators pressure technology companies in both countries to align with government strategies for economic and political influence.

The EU has been particularly active in this sphere, attempting to break the US monopoly on cloud infrastructure through data sovereignty regulations.

Nationalism à la carte

At the start of the last decade, everyone underestimated nationalism. Trump was an unlikely candidate for United States president, or at best a blip in US political history. Brexit looked equally unlikely, entertained to pacify Nigel Farage supporters. We could not imagine an all-out war between two nations in Europe.

Online nationalism is not merely an expression of history’s changing tide; it highlights changes in how we relate to, and defend, our idea of nationhood. Apart from creating new channels for the state PR apparatus, using the web to spread nationalistic content plays into populist strategies, exploiting online outbursts of national sentiment for political ends—particularly in the context of immigration.

Perhaps more importantly, digital platforms are a two-way street. They open nationalism to influence by actors beyond the state. High-profile influencers and artists shape online communities around nationalistic ideas. Hailong Liu’s work on “fandom nationalism” shows how the systematic production of memes and narratives is increasingly crowdsourced by nationalists.

The involvement of online crowds in shaping national sentiment has also made nationalism more consumer-centred. We consume nationalist content. We vote, with attention and money, for different versions of nationalism.

This plays into many governments’ attempts to use brand nationalism to support domestic economies. Consider nationalism-driven backlash, like the Twitter campaign #BoycottGermany (following Germany’s austerity measures levied on Greece), and the more recent backlash on Russia. Web3 will likely provide new ways to coordinate consumer nationalism.

As many countries move towards industrial policy, backlash against global brands who do not recognise the current flavour of local actors’ national identities may become more severe. In 2021, Mastercard faced a ban in India after refusing to adhere to local data sovereignty regulations.

Economic competition between the US and China will further fragment the technology landscape, and regulators will increase pressure on tech giants to promote national agendas. It remains to be seen how national borders will become more entrenched in online experiences, and whether Web3 will be a gamechanger.

Though the majority of nationalist content is user-generated, it seems unlikely that “decentralised” will equal “denationalised.”

03 Feb 2023

-

Michal Rozynek

02/03

Related Insights

03/03

L’Atelier is a data intelligence company based in Paris.

We use advanced machine learning and generative AI to identify emerging technologies and analyse their impact on countries, companies, and capital.