Rise of the Clones: Even Our Avatars Suffer Real-World Prejudices

In the early 1990s, enthusiasts touted cyberspace as a utopia where all could participate, free from physical boundaries and the constraints of race, gender, class, privilege, and prejudice. This "cyberspace idealism" largely stemmed from the work of cyberlibertarian political activist John Perry Barlow, whose "Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace" embodied those hopes.

Barlowe spent much of his life advocating for the absence of online regulatory censorship. He felt the right to freedom of expression, for persons and entities, far outweighed the internet's potential harms. But since its advent, cyberspace gaming and social interaction platforms suffer repeated incidents of real-world discrimination, racism, and inequality, furthering impunity by confounding traditional governance.

As the most direct, and intricate, manifestations of ourselves (and alternate identities), online avatars are consistent targets of this bad behaviour. Experts question the enhanced potential for new forms of cyber bigotry as their embodiment capabilities evolve.

The origin and evolution of avatars

The notion of an “avatar,” or extended self, has roots in Hinduism. Derived from the Sanskrit term avatarana, meaning "descent," it represents the human manifestation of a deity on earth, or embodiment of a superhuman being, often associated with the God Vishnu, whose 10 avatar incarnations descend to earth to give humanity guidance, fight evil, and restore Dharma.

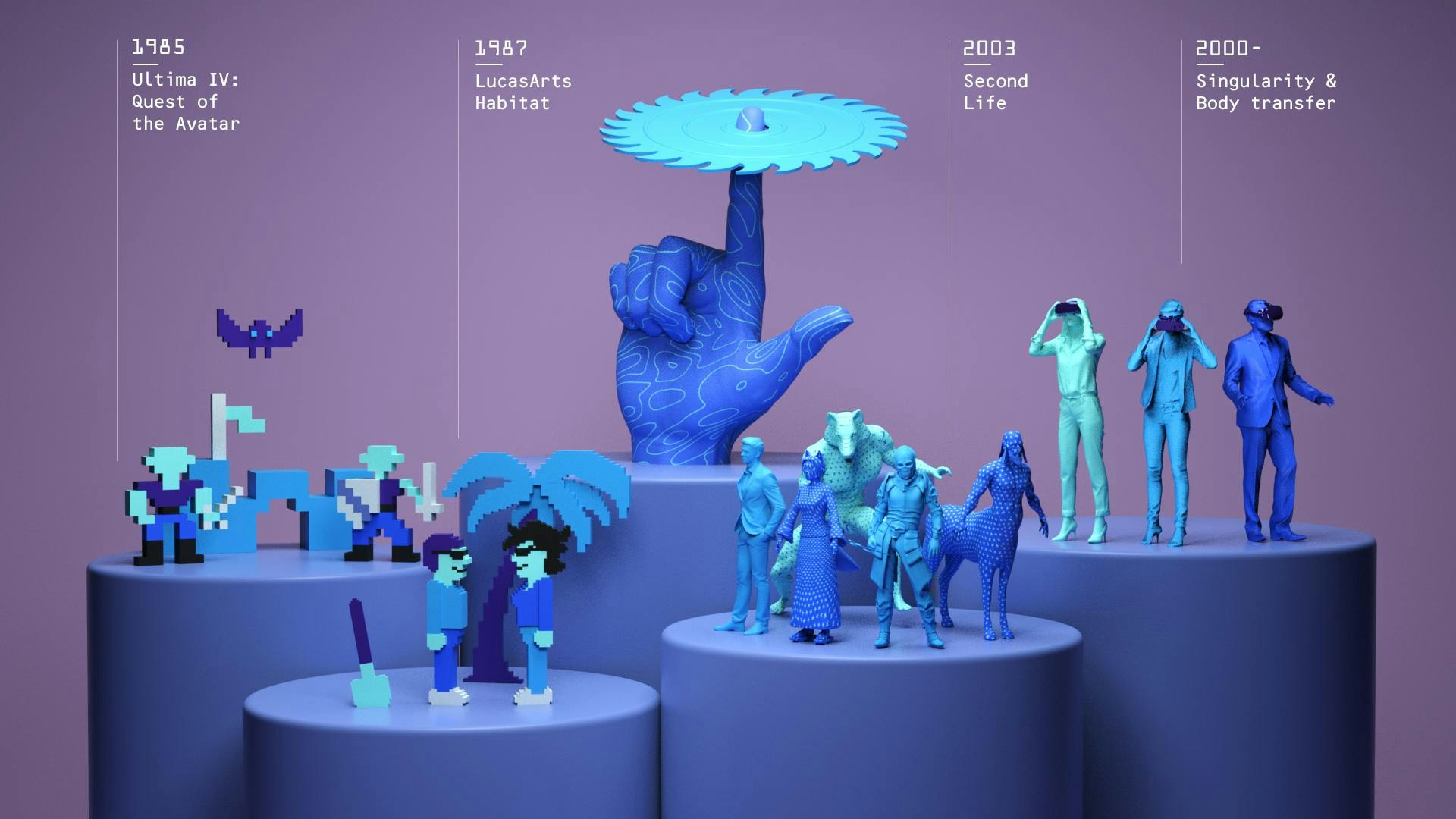

When computers became household electronics in the 1980s, developer Richard Garriott brought the avatar concept to the budding gaming community. While etching out storylines for role-playing game Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar in 1985, Garriott told the Critical Path Project that he “wanted the player to respond to moral dilemmas and ethical challenges as they personally would respond rather than as the traditional alter ego gaming characters represent.”

After scouring religious readings for ethical parables and moral philosophies to match his idea, Garriott settled on the Hindu avatar. The game follows a protagonist's struggle to understand and exercise what are known as the Eight Virtues to ultimately become an avatar, with pre-avatars expressed as small pixelated figurines. Until 1997, Origin Systems, the game’s owner, held a trademark on the term “avatar.”

In 1987, LucasArts released a massively multiplayer online role-playing game called Habitat, the first attempt at a large-scale graphics-based virtual community, available through America Online’s internet precursor, Quantum Link. Habitat’s creators also dubbed players “avatars,” and expressed them as on-screen graphical humanoids capable of moving objects, gesturing, and speaking to each other with text word clouds. The avatars had their own homes, lounged on virtual beaches, and held positions.

By 1990, LambdaMOO, a text-based cyberworld governed by its own community, emerged. Users interacted with programmable avatars, composed entirely of text. After the new millennium, virtual world Second Life debuted in 2003, enchanting “residents” by giving them expansive control over their self-representation through avatar customisations of body type, skin colour, clothing, and physical feature options. Their avatars socialise, do group activities, build virtual property, and shop.

Evolutionary Milestones: Singularity and Body Transfer

Developers always meant for avatars to serve as extensions of the self, but were too limited by nascent technologies to transfer us into the body of our on-screen, third-person personas. Since, the virtual reality platforms, gaming environments, and social spaces of the last two decades have yielded near-full embodiment capabilities for avatar and user, through sophisticated headsets, haptics, motion tracking, and multidimensional cyberspace environments.

Futurist Ray Kurzweil called this unification “the singularity,” when our technology and our selves are no longer separate. In the 2010 documentary spinoff of his book, "The Singularity is Near," Kurzweil presents a fictional avatar, Ramona, who hires civil liberties lawyer Alan Dershowitz to press for legal recognition of her "personhood" as a conscious being in a time of “fleshism,” a future form of racism that disadvantages people of virtual origin.

In our current virtual economy, aesthetic "skins" offer ways to purchase or win new physical assets, clothing, weapons, voice tones, and other add-ons for avatars. High Fidelity, a former VR congregation platform founded by Second Life’s Philip Rosedale, pioneered a way for avatar hands to more closely resemble human hand motions; meanwhile, motion capture platform Faceshift introduced facial tracking capabilities that allow avatars to mimic real-time facial expressions. The longstanding Uncanny Valley Hypothesis teeters on obsolescence, thanks to companies like Estonia-based Wolf 3D, which can instantly capture your image with an iPad or mobile phone, and turn you into an avatar for use in popular gaming and social platforms. The company’s database currently holds 25.000 scans of person-avatars.

The humanness we imbue into our separate selves has remained a constant in avatar evolution since the dawn of the internet. Regardless of shape, form, or first- or third-person representations, the deep bonds we cultivate with our avatar identities are enduring: their defeats, triumphs, and violations become vicarious memories in our peripheral and central nervous systems, a phenomenon known as “body transfer" (coined by Jeremy Bailenson), where the mind takes ownership of the avatar body. Early evidence of this appeared in Julian Dibbell’s 1993 Village Voice article, “A Rape in Cyberspace,” where he details real-life post traumatic reactions that players in LambdaMOO experienced after a series of graphic cyber-rapes committed by a character named Mr. Bungle.

"The Bungle Affair raises questions that—here on the brink of a future in which human life may find itself as tightly enveloped in digital environments as it is today in the architectural kind—demand a clear-eyed, sober, and unmystified consideration." Julian Dibbell, "A Rape in Cyberspace."

Expressions of Avatar Racism

Racism manifests as forms of prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism towards a particular group. Also, it perpetuates the belief that respective races possess distinct characteristics, abilities, or qualities that distinguish them as inferior or superior. Frequently reported scenarios of racism in the virtual world include:

- Phenotypic racism: Racism over physical traits. Since avatar skins are highly aesthetic, they create new ways for phenotypic traits to be ranked by superiority and inferiority. On Fortnite, the most popular gaming platform globally, avatars that appear too basic or cartoon-like are labeled "defects" or "noobs," and are bullied and ridiculed for their appearance, traits or perceived abilities, often driving players off the platform. Similarly, in the survival game Rust, a bald white male avatar was the default until developers randomly assigned avatars of varying genders and races to players in 2016, resulting in racial slurs and debates on internet representations.

- Despised minorities: Certain “classes” of avatars become targets of virtual violence for what they represent. In a study on gaming practices in Lineage II, Professor Constance Steinkuehler observed that Chinese gamers played female dwarf characters in order to farm in-game currency to sell to American players. Angered over the practice of in-game currency farming, Americans harassed and killed female dwarves on sight, while yelling racist and anti-Chinese epithets. Over time, this character-type became vilified and unplayable, regardless of who embodied it.

- Avoidance embodiment switch: Players who are minorities or women often switch to neutral character avatars or those of an opposite gender or race to avoid discrimination.

- Visual and voice profiling: No matter the avatar body, reports of “voice activated” racism prevail. While playing Halo 2, mixed martial artist Quentin “Rampage” Jackson spoke through a voice-activated headset to communicate with his team. His own teammates not only called him the “N” word upon hearing his voice, but also killed and betrayed his avatar.

- Exclusion: Black and Latinx characters report being entirely absent from avatar selections. Critics call this an example of racial extermination in cyberspace.

- Identity tourism occurs when we wear an avatar body of opposite race or gender to act out racial stereotypes, or for recreational purposes. Experts say attempting to pass as another, known as “cross-racial” passing, creates a false sense of empathy—or worse, further solidifies stereotypes through parody, perpetuating racism online.

While often dismissed as dark sides of cyberspace, the real-world implications of these behaviours could be immense. Imagine a virtual reality game that allowed a user to inflict graphic violence on a Black or Latinx avatar, like the 2012 #Gamergate “Beat Up Anita Sarkeesian” game that prompted players to batter the activist's face by clicking a mouse.

Cursor arrows race, like darts, toward a masked and cracking face.

Another possibility could be virtual "photoscan only" signs, similar to the "Whites Only" marquees that appeared across the United States outside businesses, phone booths, and other public areas from the late 1800s and into the 1950s, to ban minorities from entering. Will avatar creators forego specific phenotypes and design only "favoured" types, tones and features—creating a virtual extinction of certain physical human traits?

Despite decades of research, and the persistence of unruly online behaviour since the internet’s beginning, we do not yet understand the residual effects upon those who use avatars to commit immersive virtual violence, let alone on their victims.

Disinhibition and Impunity: What Anonymity Affords

Online life is riddled with what psychologist John Suler calls "toxic disinhibition," a tendency for people to violate social norms in environments that facilitate anonymity or characterisations concealing their identities, namely avatars. In many cases, the use of an avatar could encourage toxic behaviour, due to a higher likelihood of impunity.

Traditional systems of law have been of little help to ward off or punish unsuspecting racist or antagonising online behaviour. Globally, the prosecution of cyber crimes in real courts remains a fragmented, confusing array of conditions and possibilities. Since most laws are geographically jurisdictional, they have little practical application to cyberspace offences.

For example, in the United States, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act says an “interactive computer service” cannot be treated as a speaker or publisher of third-party content (apart from certain exceptions). Website owners are only required to act on serious criminal complaints, including child pornography or intellectual property claims. Harassment and discrimination victims can pursue often costly prosecution routes, including claiming defamation, intentional infliction of emotional distress, public disclosure of private facts and copyright violations (if images, likeness, or private information about the victim is disclosed).

Unintentional lawmakers

The ambiguity around applying traditional laws to online spaces ultimately places platform creators, gaming companies, developers, and even end users in primary governance roles, responsible for setting the rules of their virtual world. Popular policing methods include Community Conduct Standards or Terms of Service Agreements, and are enforced through punitive measures directed at offending accounts, like temporary suspensions or bans.

This self-governance notion is not entirely new. Habitat’s citizens and authority avatars were responsible for enforcing the platform's “laws” and acceptable behaviour standards in a world where avatars bartered for resources and could be robbed or "killed" by others. Second Life, despite “residents’” abilities to manipulate their environments, remains governed by Community Standards defined in the user Terms of Service.

Violations result in restricted access or account termination for repeat offenders. Current platforms offer “flag this content as abusive” in-experience buttons, options for immediate incident reporting, and user-activated blocking mechanisms, like Altspace and High Fidelity’s personal space bubbles. However, these options vary by virtual world and are not always readily accessible.

Foraging into Forever

Experts suggest developers consider the impacts of technology's dark side by being proactive about eliminating means for misuse, notably by baking safety into the design and development phases, leaving less room for harm, and more for mitigation. Yet there are many areas of avatar development where it is hard to define what use, let alone misuse, might look like.

Currently, “death tech,” like MIT Media Lab’s Augmented Eternity, is working to analyse people's communication and interactions, using machine-learning algorithms to approximate your personality, so you can interact with loved ones posthumously via an avatar (or other chosen form). Eternime also began beta-testing an app that analyses communications data and asks users intimate questions to create a personalised longevity avatar.

As we explore the possibility of eternity through avatars, their ability to be mistreated expands, as well as their potential to impact us in unexpected ways. Would we want our immortalised loved ones to be subject to racial epithets or slurs that discredit their legacy, 100 years from now? And how would any of us feel if a deceased loved one contacted us out of the blue, as if nothing were amiss?

A loved one's avatar could always be by your side.

18 Mar 2021

-

Jessica Buchleitner

Illustrations by Debarpan Das.

DATA-DRIVEN TECH & SOCIAL TRENDS. DISCOVERED WEEKLY. DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX.

02/03

Related Insights

03/03

L’Atelier is a data intelligence company based in Paris.

We use advanced machine learning and generative AI to identify emerging technologies and analyse their impact on countries, companies, and capital.