Shanzhai knockoff culture might kill ‘innovation’. Long live invention!

TOPICS

Grey MarketsOne winter night, a friend and I walked through the predominantly Chinese neighbourhood of Sunset Park, Brooklyn. We’d come for the food, but the ambiance was a close second; having studied in northeast China, we’re drawn to places that feel like “the real thing.” As we sipped bubble tea, he pointed to a storefront that neither of us could bypass.

Fashion Lane (时尚坊) carries an irresistible collection of sweatshirts. One dramatically reads BALELENCIAGA. A wannabe THRASHER sweatshirt bore a replica of the logo, with “TRASHER” spelled out in large text.

I was drawn to a gray hoodie with “UNKNOWN IS MY NAME” across the front and back. The next morning, I threw it on to get coffee and considered why I liked it. Found on a rack, with other garments desperate to pass for something they weren’t, I appreciated the sweater’s frank rebuff of attribution. Whether by design or happenstance, it snubs our obsession with authorship.

Brands, companies, countries, intellectuals, influencers, and startups all crave the unique recognition that comes from the belief that they’ve created something new. The primary buzzword in this endeavor is “innovation.” It appears in pitch decks, assessments of the US-China tech competition, cover letters, headlines, industrial policy, and overconfident LinkedIn bios.

If you are innovative, you are new, original, and first. You’re winning.

Talk of innovation has risen in recent decades. The internet age produces clashes between neoliberal big claims, big egos, and big rewards, and the tangible practice of innovation. But innovation is not the same as invention.

In 1939, Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter described invention as “an act of intellectual creativity undertaken without any thought given to its possible economic import, while innovation happens when firms figure out how to craft inventions into constructive changes in their business model.”

Our culture prioritises the latter. Innovation capitalism merges two fixations: being first to “make” something (or perceived as such by a critical mass), and getting paid for that ingenuity. Both are about credit and status—not making the world better, nor even creation, despite the positive associations “innovation” has come to enjoy.

George Mason economist Tyler Cowen observes invention—which innovation passes itself off to be—is actually in decline. “Americans have this self-image that we're the great inventors, [but] we've dropped the ball in many areas. We also see a lot of social tolerance—people confuse that with technological breakthroughs. [They have] a vague sense that things are getting better."

If inventiveness is in decline, then innovation in a true sense is, too. So why are public and private funders so captivated by the latter without considering whether the former is meaningfully present?

How authentification became authenticity (and innovation stopped being invention)

Innovation’s better-intentioned cousin—invention—has difficulty interacting with global trends, attention spans, and supply chains. We subconsciously accept a novelty bias, which attaches disproportionate value to technology-related “innovation” (in areas like semiconductors, apps, cryptocurrencies) and physical goods (sweatshirts, watches, purses).

For Cowen, what he refers to as “too much self-congratulations”—the PR machine of innovation—may have decoupled innovation from invention.

Gaining respect as a maker of physical goods comes with certain expectations. Physical creation is often treated as artisanal work; whether you’re Hermès or Telfar, you’re expected to be selling something concrete and tangible. Your capacity to innovate might come from your treatment of origin material, or philosophical approach to a handbag’s function. But the next world-influencing tech mogul could be any scrappy college dropout, whose promises—and deliveries on the aforementioned—can be dizzyingly slippery.

Somehow, the virtual or digital world is exempt from the quality control standards we spent centuries concocting for “the real world.”

But one mode of invention, equally perceptible in the digital and physical economy, also enjoys a subversive, largely unobserved pass from these standards: Forgery. Also known as the knockoff, items in this category could include everything from fake Gucci slides to an NFT that rips off a human artist.

Art historian Jonathan Hay argues that forgeries’ authorless nature liberates us from analysis: rather than contending with the identity or reputation of the author, the viewer must relate directly to the work, which is authorless.

“The forgery, once it is recognized as such, has no author; more precisely, it has no author function, no authorship,” Hay writes.

Consumers find this challenging. Authenticity is connected to worth; branding creates value. “The absence of an author function destabilizes because it deprives the beholder of the possibility of situating and recognizing herself in the artwork,” adds Hay. Authorless work exists as itself, rather than as a shorthand for a brand. Depending on the preferences of the viewer, this shift can renegotiate—or even erase—the metrics by which one evaluates a work’s quality.

Corporate interests prefer to keep value and branding linked. Markets are being carved out to ensure that monetisable attribution persists, even as the internet moves toward Web3’s promise of decentralisation. Take the Aura Blockchain Consortium, whose “solution” to luxury’s knockoff problem is to “empower luxury customers to directly authenticate luxury products.”

Owners of such goods could hold digital, and permanent, certificates of authenticity that move, as the item does, from one person to the next, making knockoffs—and their relative affordability—theoretically less viable.

Shanzhai: The inventive spirit of forgery

Embracing the fact of forgery could create a new assessment paradigm in the global marketplace of ideas, art, and goods. Certainly, the wild west of unattributed work poses dangers—anonymity has been among the internet’s most harmful experiments. On the other hand, focusing more on the work, and less on brand equity, could democratise credit ... not necessarily of people, but of ideas. Invention over innovation.

In a couple of generations, China has provided a grassroots example of what a possible inversion of authenticity—or rather, authentication—could look like. And it is powered by emerging technologies and targeted experimentation.

Dubbed “shanzhai” (山寨)—a term born in folk stories to refer to outlaws seeking autonomy and independence outside social norms—the country’s cultivated culture of forgery first elicited global concern in the 1950s, when small factories near Hong Kong started producing cheap, low-quality versions of major brands, like Louis Vuitton or Nike.

Today shanzhai is best associated with IP infringement. In Prototype Nation, Silvia Lindtner refers to shanzhai as “China’s partially illicit and experimental production culture.”

Shanzhai was once criticised, in China and abroad, for producing low-quality, fake and flagrantly profit-driven products (such as fast fashion), reinforcing the belief that authoritarian governance inhibits innovation—something since proven wrong, given China's current dominance in technology and the global economy at large. But it also enjoys a Robin Hood kind of “anti-authoritarianism,” where rich corporations are ripped off by clever bandits making more accessible versions of “original” products.

“Shanzhai emerged in the Western tech imagination as an alternative to individualistic notions of authorship, ownership, and empowerment, and the copy became rearticulated as an alternative to Western-centric notions of design and innovation,” Lindtner writes.

Shanzhai is no longer explicitly low-quality. As luxury brands moved manufacturing to China, factory artisans became skilled at designing forgeries as sumptuous as the real thing. Shanzhai also benefits from an open-source mentality: In the 1990s, in Shenzhen, multiple smartphone factories began sharing designs and technology.

Partly for this reason, China is no longer merely a hub for manufacturing western-branded smartphones; Chinese brands, like Huawei and Xiaomi, have become legitimate names in their own right. (Both are the world’s no. 1 and 2 smartphone manufacturers, respectively.)

The copy, then, is creative in some contexts: The forger expresses originality by selecting what to fake and why. And the collaborative nature of forgery, made possible because of the relative irrelevance of authorship, cultivates invention.

When one accepts that forgery can be an art form, Hay argues, “invention emerges as an alternative to innovation in the assessment of artistic value.”

He’s referring specifically to art and authenticity. But some of the most lauded creatives of our time are technologists; artists are no longer the sole torchbearers of “innovation,” whatever it is. Where technology is concerned, our innovative expectations are forever expanding: Innovation should be functional, convenient and pleasurable; ideally it’s also artistic, disruptive and competitively edgy.

From an innovation perspective, something great should visibly one-up its peers, the way Uber once ran circles around taxis.

When innovation dies, long live invention

The art history context is helpful, because it underlines shanzhai’s capacity to “de-westernise” originality. Hay argues that invention must be understood as a viable alternative to innovation “if the discipline of art history is to move beyond its founding Eurocentrism.”

This is part of what makes the knockoff threatening. The people who’ve gleaned the benefits of authorship are, unsurprisingly, threatened by reorientation away from authorship’s importance. This is as much the case for Silicon Valley tech firms as for Europe’s luxury brands.

“Shanzhai was seen as disassociating innovation and creativity from Western notions of the individualised-inventor,” Lindtner writes, “and it was therefore considered by some as threatening to the masculinised and individualised entrepreneurship culture of Silicon Valley.”

According to Japanese entrepreneur Joi Ito, the internet decreased “the cost of innovation” and shifted power from business executives to designers. His visit to Shenzhen, the city at the centre of Lindtner’s study, demonstrated spontaneous inventions can and should take place at the manufacturing stage. The heroes aren’t executives; they could include software developers, artisans, factory workers. “The kids in Shenzhen make cell phones the way the kids in Palo Alto make websites,” he said.

Dan Wang explains how Shenzhen’s culture created a generation that might prefer making, not merely innovating. “Producing new technology can be likened to preparing an omelet: ingredients, instructions, and a well-equipped kitchen can be helpful, but they will not in themselves guarantee a good result … An additional element is required: practical experience—skills that can only be learned by doing,” Wang writes.

“These skills can be referred to as process knowledge, and they are part of what has helped China become a major tech innovator.”

Our desire for innovation credit—acknowledgement of our authorship—is practical and psychological. “As long as we’re in a highly unchecked capitalist society, the need to be recognized for the sake of earning money and gaining notoriety are not separable,” said John Hopkins, editor of the forthcoming book Forgery Beyond Deceit, and associate professor of Art History at New York University.

In capitalist contexts, regardless of national political systems, creators face immense pressure for their work to be attached to their names, and treated as innovative—thereby worthy of notice. In Hopkins’ words, “Attention is financially incentivized.”

To conclude: Facing fears of digital 'progress'

In writing, we cite others as much to legitimise our work as to strengthen or nuance arguments. It may matter more that lots of people see it, and less whether anyone understands it. Nothing makes such entrenched elitism clearer than the threats and opportunities presented by artificial intelligence technologies like OpenAI’s ChatGPT.

When we fret about AI engendering mass plagiarism and corrupting “authenticity,” creativity might not be on our minds. Like luxury brands or tech moguls, we may instead be fretting about credit ... and by extension, our long-term relevance and survival.

As the global economic system, and its participants, continue to live and develop digitally, questions of authenticity become prescient. Our obsession with attribution, honed over the last hundred years, now collides with an unprecedented degree of competition: It’s in everything, everywhere, all at once.

The race to keep up will inevitably lead to a rise in knockoffs—online and off—of increasing strangeness and originality, the likes of which one might encounter when leaving a children’s Youtube channel on autoplay for too long. But the spread of shanzhai culture—which the young people of China have swum in all their lives—holds a promise at its heart.

There can be plenty of “innovation” in a sector, and somehow it can all look the same. Imitation is stranger. It varies in quality and approach; it can be vulgar or elegant, designed to stick out or blend in. From a sea of forgeries and knockoffs, we may well rediscover invention.

21 Apr 2023

-

Johanna Costigan

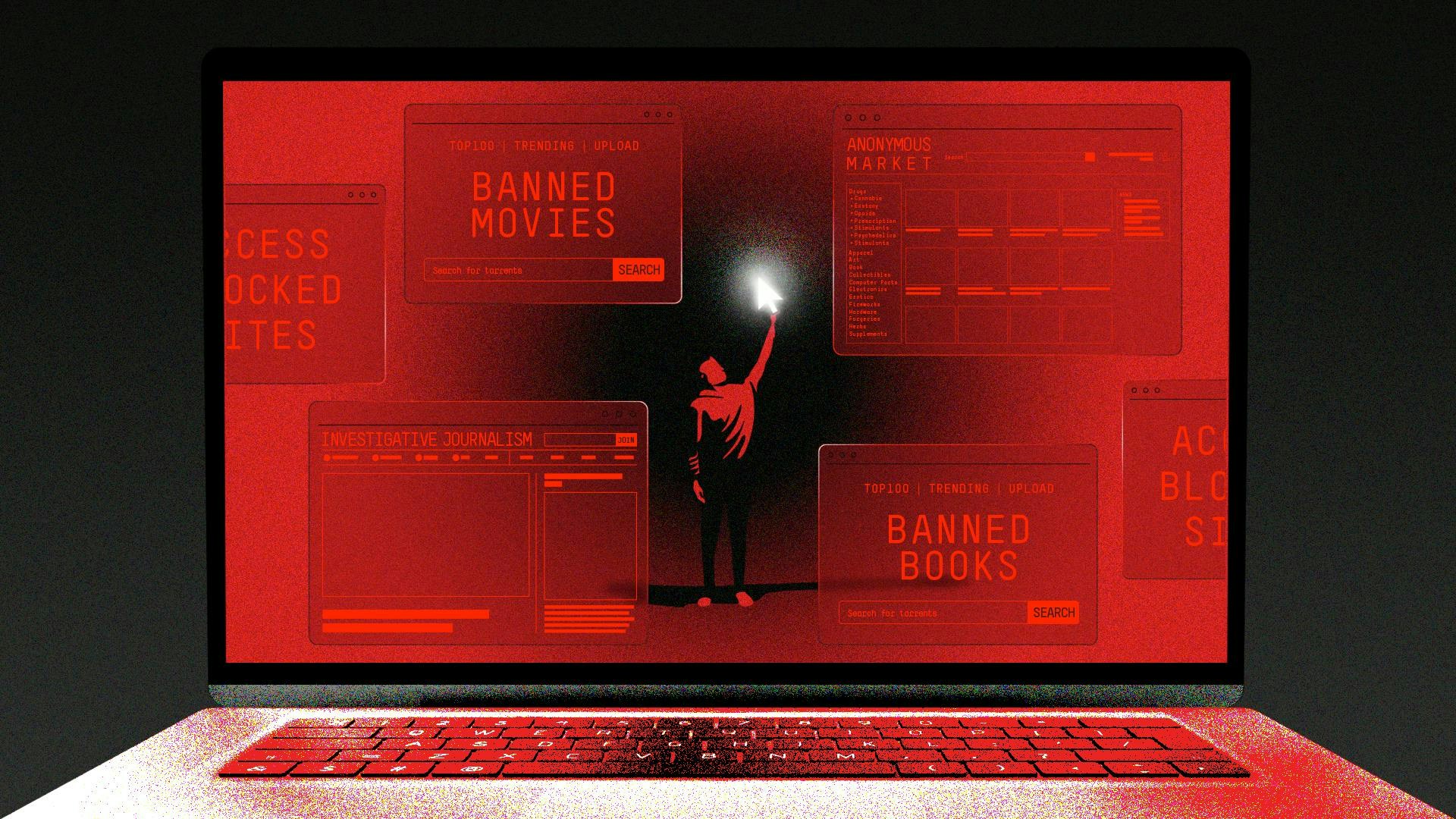

Illustration by Dominika Haas.

The future in your inbox.

02/03

Related Insights

03/03

L’Atelier is a data intelligence company based in Paris.

We use advanced machine learning and generative AI to identify emerging technologies and analyse their impact on countries, companies, and capital.