Hey, I’m an art collector! How NFTs are changing ownership

The Copperpin Gallery is an architectural marvel. Visitors move through spaces that vary from the Neoclassical, with marble staircases, to futuristic rooms with illuminating floors.

Geometric patterns are projected on the walls, framing one of the world’s most valuable art collections, with pieces by Van Gogh, Da Vinci, Vermeer, Monet and more.

It is estimated that Copperpin houses over $400 million of art ... though it hasn’t paid a penny.

It doesn’t have to. Copperpin is an online art gallery that exists within Occupy White Walls. Users can create their own galleries from a database of 6.500 pieces in the public domain.

Over 80.000 people have curated their own art collections. It’s a perfect example of the internet’s capacity to democratise access: In this case, people can not only see art but “own” a version in virtual collections.

Due to the infinite replicability of digital assets, anyone in Occupy White Walls can own a virtual Van Gogh. People spend hours building buildings to house their favourite works.

It seems that humans have always enjoyed collecting. One can add “collector” after almost any object, and the hobbyist will exist: Dolls, coins, stamps, books, cars, comic books, vintage typewriters and, of course, art. In 2020, the worldwide collectibles market was worth an estimated $370 billion. The art market is worth about $64 billion.

Psychological drivers for collecting vary, from childhood nostalgia, to the thrill of hunting down a rare item. People do it as a quest of community, or recognition; or they may simply enjoy it.

The extension of this behaviour into digital is unsurprising. The virtual goods market will reach nearly $190 billion by 2025. Powered by the creator economy, new platforms and revenue models have sprung up to not only collect but share creations, including sites like Patreon, Shopify, and ArtFinder. CryptoKitties generated over $32 million in revenue from the buying and selling of one-of-a-kind cat cartoons. Then there’s the collectibles-showcasing platforms—TokenHead, Terra Virtua and Curio.

Add to this love of collecting the hype around cryptocurrency and blockchain, plus a global pandemic with people stuck at home, and it’s clear how NFTs disrupted both digital collectibles and digital arts.

Why are artists and collectors so into NFTs?

NFTs—non-fungible tokens—are digital certificates tied to a unique digital asset, stored on the blockchain. For digital artists on social networks like Instagram and Facebook, they can represent an opportunity to earn an income.

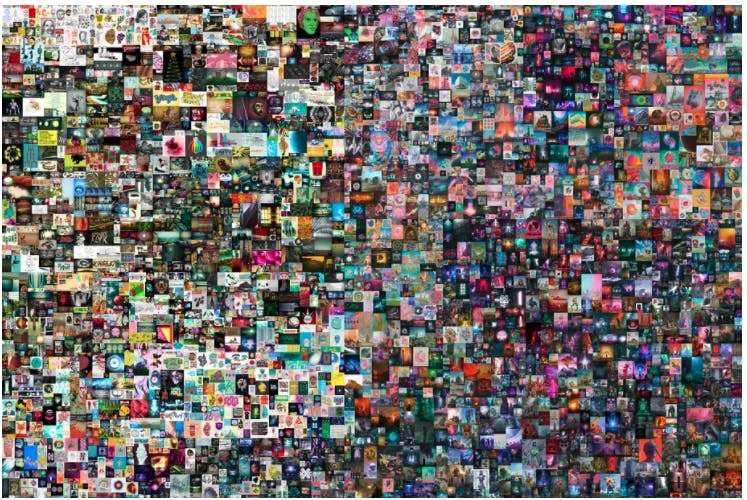

In 2021, Christie’s announced its first NFT auction, featuring the digital work of Mike Winkelmann, an artist known as Beeple. One piece, “The First 5000 Days,” sold for a record $69 million. According to the 246-year-old auction house, Winkelman now ranks among the top three most valuable living artists (Jeff Koons and David Hockney are the others)—remarkable for someone who never sold a digital print for more than $100 before the auction.

This is a welcome change for an industry where duplication usually makes creative work less valuable. For some collectors, NFTs are also a way to actively support and compensate artists for labour, even if they aren’t especially wealthy. (Most NFTs sell for far less than the ones headlines tend to favour. In April, the average price of one was $1400.)

This evolving market has pros and cons. On one hand, a decentralised marketplace enables broader exposure of artists’ work beyond the smaller (and gate-kept) traditional art market, making them easier to sell. The security and recordability of the blockchain ensures artists are compensated each time their work is sold.

But artist and developer Addie Wagenknecht cautions that we might replace one barrier of entry with another: NFT technologies are complex to understand and use for the general populace.

“Facebook won because learning to host your own sites, chat clients, and blogs was too much work,” she told Artnet. “So what is happening now is the same people who disrupted banking or technology or the web in the Valley are now claiming they have changed the world again, when really it's just the same people making the same stuff for the same people to get rich from.”

Copperpin gallery, courtesy of Occupy White Walls.

NFTs are changing ownership

NFTs make it possible to own, purchase, and sell digital artefacts in a way that wasn’t previously possible. In March 2020, Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey sold his first tweet, “just setting up my twttr,” as an NFT. It auctioned for almost $3 million.

The New York Times turned a screenshot of an article (aptly titled “Buy This Column on the Blockchain”) into an NFT that sold for almost $600.000. Research company Quartz sold rights to an article for $1.800. A collection of TIME Magazine covers sold for $435.000. And a clip of basketball player Lebron James, dunking, went for $208.000 as an NFT.

Brands are also experimenting. Taco Bell turned 25 taco-themed GIFs into NFTs that sold out in a half-hour, a strange postmodern milestone where people spend real money for digital tacos ... instead of the real thing.

Are these collectibles? To answer that, it helps to know what exactly is being collected.

“Glossed over in most descriptions of NFTs is a crucial fact: what lives on the blockchain is data describing and tracking the asset, not necessarily the asset itself,” ArtsHub observes. Put differently: NFT buyers buy the right to prove they own the digital asset in question, not the asset itself. Consider the Lebron James clip: The buyer does not own the video (hosted elsewhere); just a digital certificate that legitimizes their ownership of one specific copy of it.

Anyone can watch it online. Copies of TIME covers are easily found and downloaded. Even Beeple’s work is free to view. Yet the appeal of owning an NFTs appears to surpass the need to tangibly “own” a digital item. It’s created a different kind of scarcity—when I own a copy of a .gif, I am the sole owner of that particular artefact—without restricting others from using, downloading or otherwise engaging with the .gif overall.

In fact, the very vulgarisation of a digital “object” might make NFTs more valuable. “Ultimately owning the real thing is as valuable as the market makes it,” reads Ethereum’s official blog. “The more a piece of content is screen-grabbed, shared, and generally used the more value it gains.”

It’s a fascinating re-interpretation of ownership within a digital ecosystem. But it also marks an ideological shift, away from an “open and free web,” to a digital infrastructure centered around ownership—an attitude that counters how many platforms operate today.

'Ownership’ must also change for NFTs

The lack of ownership that characterised early dreams of an open web contributed to the visibility of digital assets, ironically resulting in astronomical sale prices for NFTs. Would the iconic “Charlie Bit My Finger” video—sold as an NFT for $765.000—be worth so much if it hadn’t garnered over 885 million views?

Ownership is also slippery; in the NFT world, the value of what you own might shift, based on the legitimacy of who is selling it to you.

This differs from traditional art, where, if a tangible object possesses a certain value, then that value generally holds in the marketplace. In the case of NFTs, the copies of a video clip or .gif are, in their way, “genetically identical” to one another (at least from a pixel perspective). But because it’s so easy to replicate them, regardless of their value, it is also very easy to sell them.

And who should have the right to sell an NFT—thereby claiming ownership to some aspect of its value—especially if the cultural currency of a digital artefact scales?

Van Gogh’s Sunflowers was personally valued by the artist at about $125. In the 1980s, well after his death, it was sold at Christie’s for nearly $40 million.

This is not uncommon with “fine art,” but it invites speculation about how the practice of selling and promoting artists’ work will extend into the digital space—now and posthumously, when the value of works can sometimes explode. If the use case for art is hardly clear-cut at scale, it’s more complicated for artefacts like GIFs, memes, and other pieces of the web.

The Big Idea details several examples of artists who saw their work sold as NFTs, without their knowledge or consent. “The value proposition of NFTs is that the proof of work ensures your original piece has a unique token attached to it, which means that the person who owns it knows they have the original,” they write. “But the problem is that someone can take a JPG and throw it up on a different marketplace with a different token attached to it and sell it. There is no ‘original’.”

This happened to artist Corbin Rainbolt, who discovered someone created NFTs of all his tweeted illustrations.

No formal copyright checks exist to create an NFT. OpenSea and Rarible, two major NFT platforms, require no verification before minting one. A user simply needs an Ethereum wallet, and funds for transaction fees. So the technology, designed to instill proof of ownership of digital assets, can be easily manipulated by those with no legitimate ownership at all.

Thus buyers who pay a premium for “rare” NFTs have no guarantees or legal protection against the NFT author—or anyone else, really—minting more copies of the same asset. Authors can even mint different versions of the same asset across various platforms, then claim each is one of a kind.

Protecting your asset, and NFTs' environmental impact

NFTs are certificates that contain a link to an asset. If the link stops working, the NFT itself could become meaningless.

This risk is being addressed. More NFTs are hosted on IPFS (InterPlanetary File System), a peer-to-peer hypermedia protocol that makes it safer (and faster) to store data on the web. Buyers of NFTs would do well to ensure what they’re buying is already IPFS-hosted.

Other risks include the degradation or obsolescence of technology—marketplaces going out of business, or users forgetting their wallet password. Cyberattacks also accompany rising NFT popularity. Nifty Gateway has been hacked, with multiple users’ NFTs stolen and resold.

As technology evolves, so will implications on what rights are gained when purchasing one. Currently, intellectual property rights remain with the original creator unless otherwise specified, so the benefits of “owning” an NFT, at least as more than a speculative asset or collectible, are currently limited.

Then there are environmental costs. According to NFT carbon footprint calculator Carbon.fyi, an NFT of Space Cat (a gif of a cat heading to the moon) generates the same carbon footprint as an EU resident’s electricity use in two months. Cambridge University noted that mining Bitcoin consumes more energy per year than Argentina.

The Ethereum blockchain, the basis for NFT creation, has an enormous environmental footprint and is intentionally designed that way. Energy inefficiency supposedly acts as a barrier to users tempted to tamper with the ledger. But the environmental impact of blockchain technology cannot be overlooked. Climate change scholars say Bitcoin emissions alone could “push global warming above 2 degrees Celsius.”

Despite the availability of other, greener, blockchains, those already invested in particular currencies will be hard-pressed to change unless forced. Governments are contemplating legislation around cryptocurrency regulation in general, and environmental impacts in particular.

The European Commission's proposed regulation, “Markets in Crypto-Assets,” would regulate both crypto-assets and service providers in the EU. One suggestion includes the implementation of EU-wide crypto-currency trading licences. Other countries, like China, Britain, and Russia, are considering state-backed central bank digital currencies.

Are NFTs actually 'good' or 'bad' for art?

NFTs are a means to create a secure, authenticated way to sell, purchase, and store digital assets, which many took to mean they would revolutionise digital arts and collectibles. Reality is more complicated.

Some worry that the cryptocurrency community deliberately inflates the value of NFTs for their benefit. David Gerard, a cryptocurrency researcher, elaborated on such dark agendas: “NFTs are entirely for the benefit of crypto-grifters,” he wrote. “The only purpose the artists serve is as aspiring suckers to pump the concept of crypto, and, of course, to buy cryptocurrency to pay for minting NFTs.”

Beeple’s Everydays: The First 5000 Days, a collage of the 5000 images he created over 13 years, an NFT of which he sold at Christie’s. Courtesy of Beeple.

Remember that $70 million sale of Beeple’s artwork?

The buyer was Vignesh Sundaresan, founder of Metapurse, a Singapore-based crypto investment firm. Per journalist Amy Castor, “Metapurse has taken Beeple’s multiple artworks, or NFTs, along with three virtual museums, and combined everything into a ‘massive bundle.’ Would you like to invest in this wonderful package? You can. All you have to do is stock up on Metapurse’s new B20 token.”

Metapurse says it’s about the democratisation of art. But Castor revealed that Sundaresan owns 59 percent of all B20 tokens and he has a pre-existing business relationship with Beeple, who owns 2 percent of B20 tokens. It is not hard to argue they had a vested interest in publicity from the historic sale, and a stake in the industry’s success.

Author Seth Godin calls NFTs a dangerous trap for creators because they encourage a misalignment of values. “The more time and passion that creators devote to chasing the NFT, the more time they’ll spend trying to create the appearance of scarcity and hustling people to believe that the tokens will go up in value,” he recently wrote. “They’ll become promoters of digital tokens more than they are the creators.”

He goes on: “The trap, then, is that creators can get hooked on creating these. Buyers with a sunk cost get hooked on making the prices go up, unable to walk away. And so creators and buyers are then hooked in a cycle, with all of us paying the lifetime of costs associated with an unregulated system that consumes vast amounts of precious energy for no other purpose than to create some scarce digital tokens.”

The promise—that NFTs facilitate sustainable digital creation—strains under consumption models that replicate the same elitism and scarcity found in the real world, and contributes to a more fragmented and privatised web. And while some artists use NFTs to generate revenue, it remains to be seen whether this business model remains viable … and if it will be accessible to all, not just a few.

Despite technological advances, little has changed on the ground. Cryptocurrency billionaires replace wealthy art collectors as gatekeepers of a speculative asset class, resulting in wild, unpredictable valuations of goods. Ecologically, NFTs may be a bigger burden than their physical counterparts.

Still, it will be interesting to see if tomorrow’s collectors are unburdened by the need to physically own their assets of predilection ... and whether the coup-du-coeur that strikes us when confronted by certain pieces of art can be replicated in pixels.

In Occupy White Walls, players say they feel that same profound pull when curating digital collections. But in the NFT world, it may be that the receipt matters more than the asset itself.

08 Oct 2021

-

Rahaf Harfoush

Illustrations by Macha Pulcini.

DATA-DRIVEN TECH & SOCIAL TRENDS. DISCOVERED WEEKLY. DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX.

02/03

Related Insights

03/03

L’Atelier is a data intelligence company based in Paris.

We use advanced machine learning and generative AI to identify emerging technologies and analyse their impact on countries, companies, and capital.