Xi reforms underline tech's role in China's 'common prosperity'

Recent reforms instituted by Chinese president Xi Jinping—which shall affect the tech sector and the Chinese people's participation in the virtual economy at large—have been described as a turn to Maoism, a warning for rich capitalists, and the “Red New Deal.”

The reforms propel Xi’s priorities for China’s socioeconomic future, where technology helps monitor and quash potential sources of social conflict.

But Xi’s government is not interested in becoming secondary to China’s big tech firms, nor in punishing them; instead, the motivation is to rein in how much tech expands China’s public sphere, and maximise digital's ability to nudge behaviour toward party priorities.

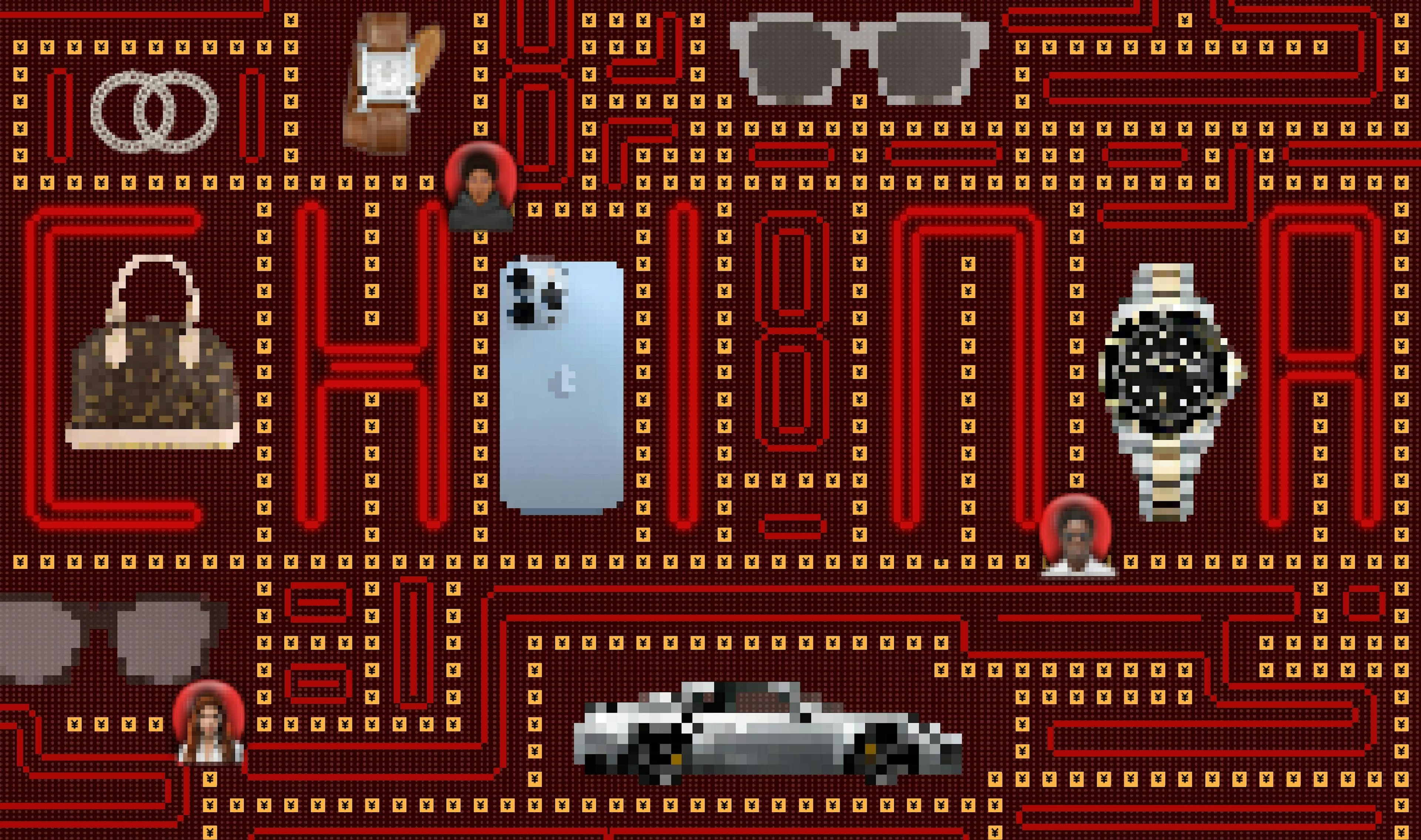

Individually, this means curtailing certain forms of internet use: Capping the time minors spend playing video games to three hours a week, removing dozens of fan accounts on Chinese social media platform Weibo, and mandating that broadcasters portray party-approved versions of masculinity (they must “resolutely put an end to sissy men and other abnormal aesthetics”).

On a macro scale, policy from these reforms incorporate Xi Jinping Thought into school curricula, from primary school to university; focus on “cultivating love for the country, the Communist Party of China, and socialism”; and limit legally available extracurricular and online English language instruction. The latter is a huge industry that Chinese parents rely on to differentiate children in a competitive academic environment, and that foreign teachers rely on to make a living.

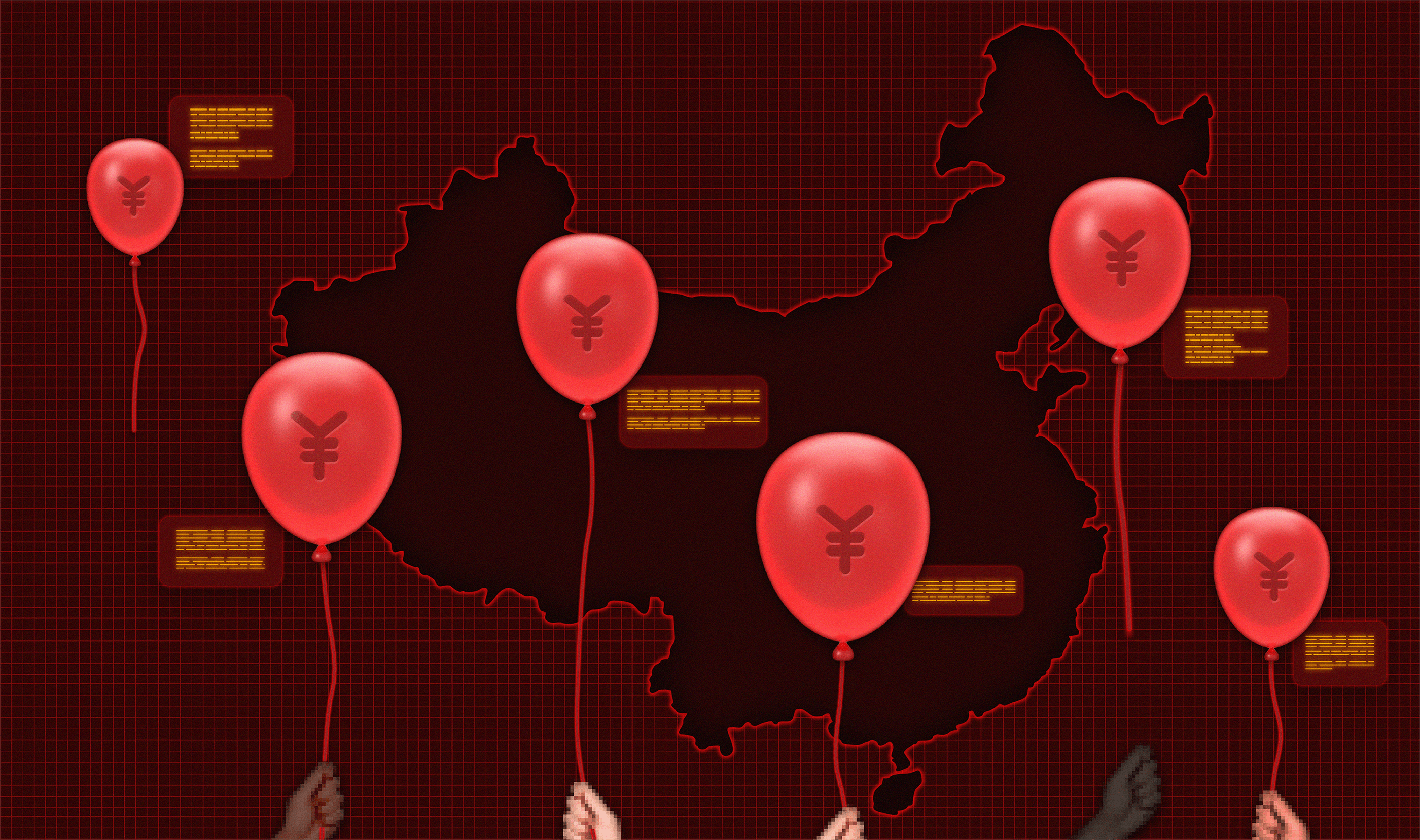

Further reforms ban cryptocurrencies and seek to de-monopolise Jack Ma’s Ant Group, which expands from Beijing's decision to halt the company’s planned IPO last November.

“We shouldn’t forget that this is a local manifestation of a global phenomenon, and that global phenomenon is: We don’t like big tech anymore,” Rogier Creemers, assistant professor in modern Chinese studies at the University of Leiden, said in an interview.

Creemers compares China’s data protection laws to Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), noting that similar strategies are perceived differently, depending on the governance structure of the nation in question. “‘Authoritarian’ is usually the qualifier, but very often states do something simply because they’re a state,” he added.

Global trends toward tech scepticism aside, Xi’s reforms are also manifestations of unique goals, informed by the ideological and historical forces that constitute CCP legitimacy: Progressing down the socialist path, and achieving the elusive goal of “common prosperity.”

The context of modern China

It is impossible to know the full calculus behind Xi’s hopes for what can be understood as “trickledown” common prosperity. While his aim of levelling the playing field is likely also driven by a motivation to maintain personal and party power, his reforms will make at least a small dent in China’s rampant inequality.

Multiple situational factors drive Xi to pay close attention to that. Among them: Millions of Chinese remain impoverished, while a concentrated segment of coastal cities inhabitants gets rich; demographic shifts require offering financial incentives for families to have more children; and the sense that President Biden is not pivoting from Trump’s China policy, but largely staying the course of conflict, albeit with finer rhetoric.

European sanctions on Chinese goods, following the state’s repression of Uighurs in Xinjiang, reinforced western willingness to penalise China on moral grounds. And President Biden's current approach to China signals that if the latter wants to play a part in how the decoupling of US/China interests is perceived domestically, it must control its internet, the companies who develop it, and the money made and moved on it.

Xi’s speech on his reforms, published in the party journal Qiushi (“Seeking Truth”), emphasises that common prosperity is the product of collective effort. It singles out the necessity of “avoiding” anti-hustle sentiment amongst young people, dubbed “lying flat” (躺平)and “involution”(内眷). The “lying flat” movement rose in response to the toxic demands of study and work culture that dominate middle class urbanism in China. "Lying flat" supporters might manifest opposition by quitting tech jobs, for example, or moving to the country to pursue art full-time.

“Special attention is being directed to removing obstacles hampering fairness, justice, and common prosperity,” reads a recently-issued white paper from The State Council Information Office. Titled “China's Epic Journey from Poverty to Prosperity,” the report also contends that “housing is for living in, not for speculation”—potent, given Evergrande's recent collapse. It concludes by asserting that the reforms “guaranteed that the goal of building a moderately prosperous society in all respects has been realised on schedule.”

Unlike other national leaders, Xi isn’t paralysed by a need for consensus. He can unilaterally enact reforms. But these particular adjustments are not only designed to reform China economically, which would be achieved more effectively with changes targeted to taxation and social welfare policies. Xi's priority is illuminating social exemplars … as well as who’s in the dog house.

Fintech is one such dog. “The Chinese authorities see the financial system as a handmaiden to the rest of the economy,” Creemers said. “It is not supposed to play a dominant role in GDP growth because the bigger your financial services sector gets as a percentage of GDP, the more volatility is introduced. If there’s one thing Beijing does not like, it’s volatility.”

He pointed out that when the US and Europe regulate, they do so based on open-ended principles, like privacy. “The Chinese government, however, acts purposefully and situationally,” Creemers continued. The CCP does not regulate based on timeless principles, but in reaction to visibly emerging trends or problems.

Researcher Lillian Li echoed this in a recent edition of her newsletter. “As their legitimacy is built on providing Chinese citizens with better lives, they have to accommodate that in each economic environment,” she writes. “The Chinese government is doing what it has always been doing—adapting.”

The teleological clock has turned. China’s ability to lead the world in AI research via Shanghai and Shenzhen, when tens of millions of citizens don’t receive basic education, is no longer sustainable. But the regulatory overhaul necessary to bridging gargantuan rural-urban and rich-poor divides would introduce too many opportunities for instability.

On the other hand, curtailing minors’ video game time or participation in celebrity fan clubs is feasible, enforceable, and sends a message: China’s future relies on cultural alignment between people and party, not people and hobbies.

The origins of 'common prosperity' doctrine

In CCP political philosophy, the People's Republic has undergone three eras, led by its most important leaders: Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping, and Xi Jinping. Amidst other benchmarks—mandated by Marxist roots and the politics of these men—exists the promise of achieving common prosperity.

All three leaders were also expected to embody morality, a longstanding requirement for China’s leaders. “The key for Chinese Emperordom was virtue,” Creemers said. “That’s still the core of CCP political philosophy; if you stop being virtuous, you stop being a ruler. The party includes morality in its approach to governing society in a way that is unimaginable under western legal order. And its absence is unimaginable in the Chinese context.” Thus it is not a wild departure from political tradition for the government to weigh in on how people spend time on the internet.

Mao invoked “common prosperity” in reference to a utopia no analyst considered feasible at that time, given the absence of economic cogency in extreme collectivist policies like the Great Leap Forward. A 1953 People’s Daily article, part of a series titled “Promoting the General Line to the Peasants,” suggested two possible development paths: Capitalism, where a few get rich (first) and everyone else is impoverished; or socialism. “Therefore, the development of mutual aid teams and cooperatives can not only avoid division among the peasants and avoid the path of capitalism,” the party article asserted, “but can also enable peasants to achieve common prosperity step by step and finally reach a socialist society.”

In terms of economic policy and reform, Deng Xiaoping pushed for practicality, shelving “common prosperity” as a distant—though important—goal for future leaders to address. Unlike Mao, he did not frame it as an achievable outcome of collectivism (nor was he interested in pursuing it after Mao’s failures). But like Xi and other adroit CCP officials would do later, he mindfully framed deviations from party doctrine as reinterpretations.

Thus there is no disagreement between the CCP’s circa-1950s characterisation of capitalism as “a road of a few getting rich,” and Deng’s famous reform-era line, “Let some people get rich first.” A People’s Daily article, describing Deng’s definition of “common prosperity,” put it thus: “Marx and Engels’ thoughts of common prosperity paint a preliminary outline for the basic characteristics of the future socialist society, and also point out the direction for the later construction of a socialist country.”

In other words, there is nothing wrong with the Maoist concept of common prosperity; it’s just that China wasn’t ready.

Nor was it ready under Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, who followed Deng. Both largely sought to maintain Deng’s economic reform agenda, while contending with domestic issues like urbanisation and population growth. They also had to find a way to continue economic growth in eras characterised by the globalisation and digitisation of the national economy, despite China’s closed internet. The “some” permitted to “get rich first” were left to go on doing so.

“My sense is that Xi is a very different character from either Deng or Mao, and in part that’s a product of the times,” said University of Pittsburgh political science professor Kay Shimizu. The CCP historically ruled the country with strong leadership at the helm, but that was simpler when China’s economy was less developed. Now that it is on the brink of middle class status, new economic issues and governance responsibilities are coming to the fore.

Technological change has more deeply integrated global society. “China’s economy can’t exist in isolation as it did during the Mao era, nor can it benefit from having come out of isolation at a very low level of economic development as it did under Deng,” Shimizu continued.

If the time for common prosperity is now, then Xi’s recent policy manoeuvres are a logical progression of previous CCP development goals. Abigail Coplin, postdoctoral associate with the Yale Council on East Asian Studies, observes significant similarities between Xi’s September 11, 2021 speech on science and technology policy reform, and a speech delivered by Deng, four decades ago.

“Xi’s speech, like Deng’s in 1978, seemed tuned to build bridges and alliances with a group not fully on board—reaching out to experts irked by the state’s repeated interventions,” she writes. “Moreover, given its dominant historical continuities, Xi’s speech did not seem to represent a policy departure, but rather a reiteration of longstanding party-state goals.”

Embedded in Xi’s policy sweep is the conviction that he can “do both”: Create a (limited) collectivist utopia, while maintaining and strengthening China’s global economic dominance. This effectively casts him as the protagonist of the CCP’s larger historical narrative surrounding China’s development and state-enterprise dynamics.

Party announcements about the reforms link this new development phase to Xi Jinping Thought—Xi’s political philosophy, enshrined in the Chinese Constitution (like Mao’s and Deng’s). By selectively picking up from where his two most significant predecessors left off, and highlighting his ability to live up to those vital legacies, Xi positions his upcoming (though not inevitable) third term in office as a continuation of the Chinese economic development model’s emphasis on equality.

Meanwhile, official descriptions of common prosperity are getting more realistic—tamping down dramatic rollouts to make enforcement easier to conduct over time. Factors like geography and development level inevitably affect the speed and degree of “common” prosperity. As if acknowledging this, the People’s Daily asserts, “Common prosperity is not equal prosperity… [it] is not just a slogan, but a visible, tangible and real fact.”

Common prosperity versus capitalism ... and where tech fits in

“Returning to the party’s ideological roots, officials are likely looking around the world and saying, ‘there is a point to us being a Chinese Communist Party with socialist ideals’; everyone should have equal access to basic needs like education and healthcare,” Shimizu said. Chinese leaders likely examine rich, unequal, and unstable countries and think, this is not where we want to end up. “If the same proportion of people who died of Covid-19 in New York died in Beijing, there would be no CCP, no Xi, it would be over.”

Despite stringent top-down control in China, real expectations must be met to prevent mass uprisings. “In some ways, Xi is probably very jealous of the American system in the sense that Trump could get away with that and stay in power," Shimizu continued.

China's efforts to contain the virus was not a natural byproduct of authoritarianism; it was necessary for regime stability—explicitly because the Chinese people expect safety and security from the state, which is broadly what makes them willing to forego many personal freedoms. Stability is not only coveted by the state for its interests; it is a service it must provide.

However, Xi does echo the CCP leadership narrative about China’s existential combat against capitalism. A piece from the Jinping Thought Q&A series, in the People’s Daily, reads that “competition between the two ideologies and systems of socialism and capitalism has never stopped.” Linking the threat of capitalist ideology, and destabilising colour revolutions, the piece asserts that “hostile forces”—a euphemism that often refers to anonymous westerners—never ceased attempts to sabotage the CCP’s socialist system.

But in certain contexts, the people may also prefer to protect themselves. “These regulations, especially the ones in the education sector, not only stifle private business innovation and investment, but also cause outrage amongst a highly influential group, perhaps the most likely group in China to upend social stability: Mothers,” says Shimizu. In the wake of the Xi’an earthquake, and the 2008 contaminated milk scandal, for example, Chinese mothers caused the most trouble for authorities. “They’re difficult to arrest,” she added. “Even Xi Jinping has a mother.”

While she believes the government is taking major risks, she has no doubt that those in charge of enacting these reforms have considered the consequences. They bet on the ability to appeal to the general public with the pitch that this is a sincere effort to bring equal education access to all.

Chinese leaders likely consider social tensions in the United States—police brutality, the Black Lives Matter protests, the sheer number of Americans who died of COVID-19—and astutely link these problems to rampant inequality. “The CCP wants to at least show that it is making an effort to address issues of inequality while also taking greater control over education itself," Shimizu said.

Given the degree to which global tech firms are known to take advantage of personal data to monetise a wide variety of uses, China is acting in terms of rational interest, not as an authoritarian caricature. Its regulatory goals are reasonable, whether judged by domestic or foreign standards. As Professor Shimizu put it, “When it comes to corruption in the Chinese public sector, especially between tech execs and high up party officials, we only know the tip of the iceberg.”

Despite the imposition of regulations aimed at China’s rising tech stars, the party is not naïve to the benefits of digital development. Creemers says Xi is not trying to punish big tech execs; he wants to rein in their products so that they operate under the government’s watch. This offers real protections to consumers from nefarious business interests.

It also gives the state a higher degree of control over how digital forces shape society. “You need ever-greater informational capturing and processing power in order to further discover the laws by which society functions—and by which society can be predicted and controlled,” Creemers said.

After stability and security, prosperity is on deck. If Xi fails to push China forward before stagnation occurs, he faces long-term risks. He must remain a few steps ahead at all times … and one of the best ways to stay ahead of the game is to engineer it.

“Having been in the centre of power for so long, and before that, being stationed in rural parts of China, Xi’s gut instincts tell him this is the time to act,” Shimizu said. “Because if not, 10 or 20 years down the line, there would be a major disaster for the party and the country.”

This article is part of a series about the People's Republic of China and its relationship to technology. Previous pieces appear below.

22 Oct 2021

-

Johanna Costigan

Illustrations by Dominika Haas.

DATA-DRIVEN TECH & SOCIAL TRENDS. DISCOVERED WEEKLY. DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX.

02/03

Related Insights

03/03

L’Atelier is a data intelligence company based in Paris.

We use advanced machine learning and generative AI to identify emerging technologies and analyse their impact on countries, companies, and capital.