Are technology and religion such unlikely bedfellows?

“Online, contrary to Nietzsche's allegation, God is most certainly not dead. The web is littered with sacred spaces and, if anything, He (or She or It) has been released from traditional doctrine to become everything to everybody.”—Psychologist and journalist Aleks Krotoski

Religions adapt; they are not mere artefacts of a quaint past. Today they are deeply enmeshed with modern technologies.

As a western European from an urban capital, I learned to draw a line between tradition and modernity ... and, by extension, to oppose religiosity and technology. Does this distinction stand up to scrutiny?

Those oppositions, tradition/modernity and religion/technology, resemble their more commonly-discussed cousin, offline life versus online life. Professors Mia Lövheim and Heidi A. Campbell observe that “online” and “offline” can no longer be seen as “completely distinct fields of practice, as for many they are integrated spheres of interaction.”

Indeed, when the ability to create is given to people in cyberspace, they may opt to incorporate elements of religious practice. Tech and religion are intertwined … and, like all things in interaction, impact one another’s evolution.

MAINTAINING THE SUBSTANCE, ADAPTING THE FORM

In the 2010s, in the virtual world Second Life, we witnessed the (re)creation of cathedrals, among other spaces of worship. Players had infinite possibilities to modify and customise items; they facilitated others’ ability to attend ceremonies and other rituals.

Religious bodies also create and adapt items meant to ease worship in digital times. In 2019, the Catholic Church launched a “click-to-pray e-rosary,” which “serves as a technology-based teaching tool to help young people pray the Rosary for peace and to contemplate the Gospel.”

"Garden of Capnam," Genesis 2015, Dan Hernandez.

Like any traditional body adapts communications strategies to modern audiences, religious bodies adapt to changing norms. Tools adapt in kind; technology is sometimes designed specifically to accommodate belief-driven lifestyles.

The Salamweb browser was created in 2019, to facilitate “Muslim-friendly web surfing” among followers of Islam. It can notify users of prayer time, indicates the Qibla (the direction to Mecca), and triangulates nearby mosques. It also claims to be a Shariah-compliant web service, warning users when they are likely to encounter pornographic or gambling-related content.

In 2005, Motorola devices were created for ultra-orthodox Jews. They were dubbed "kosher-compliant," since internet access, as well as messaging and videos, was disabled. Dr. Campbell, who specialises in digital religions, called the kosher phone’s launch a “unique example of how a religious community may re-design a technology so that it is compatible with its standards of practice."

Because conservative religious groups, like those who practice ultra-orthodox Judaism, follow strict cultural and ideological rules, this also illustrates what’s at stake when trying to adapt technology to religion, or vice-versa.

These particular adaptations build upon existing practices, rather than making new ones. If you can’t perform Umrah, the annual Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca, it has traditionally always been possible to ask someone to go on your behalf. Today someone can livestream that journey for you. Ahmed Alhaddad, founder of iUmrah.World, an app that connects people to surrogates willing to perform this task, sees this as a natural contemporary adaptation of the latter loophole.

In a similar “extension of offline sacred spaces,” the Western Wall in Jerusalem is now livestreamed, thanks to services provided by the digital community Aish HaTorah. At one point people could even tweet prayers, which were printed and placed “into the interstices of the physical wall.”

"Descent of the Famiconi," Genesis 2015, Dan Hernandez.

THE GAMIFICATION OF RELIGION

Tech’s gamification culture has also wiggled into religion, often to make teachings more accessible and entertaining. Follow J.C. Go! is a Pokemon Go copycat created by a Catholic evangelical group, ahead of a youth event in 2019. The game Muslim 3D educates pilgrims about Hajj principles in a fun, accessible way.

Gamification also cultivates new means to foster spiritual devotion. In 2012, Andy Robertson, a theologically-trained video game and tech journalist, organised a gaming-led communion service in Exeter Cathedral. As believers chanted, they could manipulate a Playstation controller to simulate, on-screen, the path of a flower petal swirling in the wind above luxuriant hills (courtesy of the game Flower).

Robertson believes video games, like any art, address emotions and the heart, creating space for divine dialogue. When asked about it, Reverend Stephen Santry explained:

“It was revolutionary to understand that game developers create spaces or worlds for people to explore and discover. This is also the domain of a priest. In facilitating acts of worship I create an environment for people to have an encounter with God.”

Virtual reality is also stepping in when believers cannot access sacred space. This became a major issue during the Covid-19 pandemic, when people could no longer gather in places of worship. Solutions like Labbaik VR promotes its virtual Hajj as a viable alternative for pilgrims, as well as an educational tool.

"Overworld," Reset, Dan Hernandez.

RELIGIOUS MODDERS & BELIEVERS ARE ONLINE

Technology doesn’t only enable classical practices to meet modern needs. As online platforms became favoured means for conveying messages, they empowered intermediary authorities and “non-expert” voices to advance their own interpretations of sacred documents.

A few examples include a popular nun, Sister Bethany, on Twitter; a pastor who used TikTok to praise Chai tea; Daoist masters that use websites to promote Feng Shui consultancies; and feminist woman rabbis on Instagram.

Many of these voices can sound to some like a breath of fresh air. But with more nuns and monks turning to Twitter or Facebook, religious authorities have also stepped in to negotiate traditional values into the digital morass. The Pope tried setting precedent here: In 2018, the Vatican published a document that urges nuns to use social networks with "sobriety and discretion," in hopes that they “not be used as a way of avoiding fraternal life.”

This multiplication of voices goes beyond religious authority figures. Believers, whether novices or long-standing participants, have also become active modders of belief.

This is especially noticeable when contemporary practices encroach on religious ones. The now-infamous Christian YouTube channel Girl Defined went viral after posting videos like “Should Christian Girls Send Nude Photos?” and “Should Christian Girls Use TikTok?"

But these informal discussions by non-authoritative figures feel relatable to viewers who struggle to find answers to touchy immediate questions. No surprise, then, that Mennonites and Amish people are trendy on TikTok, and Mormon mommy bloggers take off: Unlike nuns or monks, they’re people trying to live ordinary lives, balancing modernity and modern tech with ascetic lifestyles.

These movements embody how religions change, and model new ways to perform belief in life. They do this by either addressing possible ideological conflicts between belief and technology, or advancing techniques that harmoniously unite them. Renewed interest in modern witchcraft, and by extension paganism, is a non-negligible example of this.

"Portal 2019," Reset, Dan Hernandez.

TIKTOK WITCHES & TECHNO-PAGANISM

Modern and western practices of witchcraft were already in fashion in the 1970s, thanks in part to the New Age movement. But social networks are fertile ground for them to grow anew. The witches of TikTok, associated with the hashtag #witchtok, had 19,6 billion views as of October 2021. Witches also proliferate on Instagram, with accounts like Witches of Insta or The Witch of the Forest, who have over 950.000 followers between them.

Some attribute this popularity to modern witchcraft’s marketable aesthetic and accessories (gems, potion phials, candles). Others feel it’s come at the right time. A Quartz article, “Witchcraft is the perfect religion for liberal millennials,'' argues that the modular nature of witchcraft, and its relative anti-institutionalism, make it a perfect spiritual outlet for young progressives who increasingly define themselves as atheist.

The return of witchcraft may also signal another current phenomenon—the individualisation and specialisation of religious practices, pushed by social media.

In conversation with L’Atelier, Dr. Campbell explained, "What we’re seeing is much more diversification and specialisation online. It’s a form of tribalism [...] People are seeking out highly specialised connections and groups, like: ‘I’m Southern Baptist but I believe in gender equality and gay rights. So I’m going to find my subgroup’. It’s allowed much more diversification and specialisation rather than a common ground."

This brings us back to the woman rabbis on Instagram, advocating for a feminist Judaism. The internet generalised the practices of “finding someone like you” and “shape it as you go” over decades; even religion is not exempt.

Dr. Campbell suggests that internet affordances—live services, apps, readily-available sacred texts—might inspire more personal approaches to religion. Asked whether individualised practice is religion’s future, she replied, “I think so. This is a broader trend in digital culture. Scholars call it ‘network individualism’. Because in traditional communities relationships are based on connections to institution, the family, the geography that is what defines who’s part of the communities, who’s not." On the other hand:

"In the digital world, I choose my community, I create those connections, I decide how much I’m invested in them: I’m much more empowered."

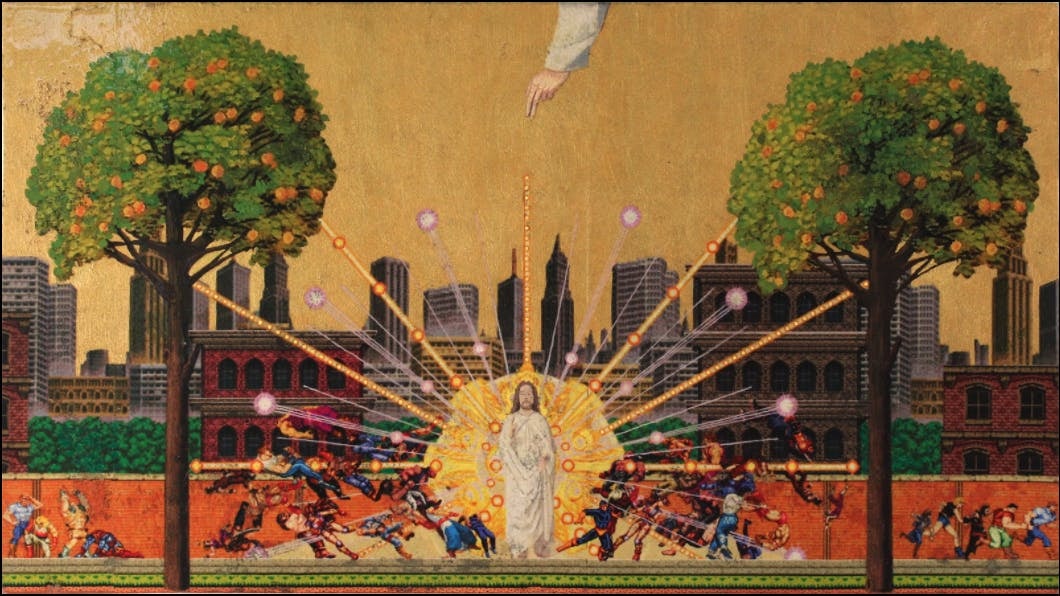

"Transfiguration," Game Over, Dan Hernandez.

The individual nature of community-building is now an assumption with which people, especially younger ones, often approach the internet, Dr. Campbell notes. “The community isn’t something I take on [anymore]; it’s something I create."

No wonder techno-paganism is so appealing. It speaks to a society where individuals are part of a personally-tailored community, an “ego-network” that the internet magnifies. This is unlikely to change, suggests Dr. Campbell. “Digital culture is always going to push people toward individualism.”

The internet and social media have opened the door to more personalisation and hybridisation, but do not appear to have transformed our approach to the mystic. Have religions been changed by technology? Fundamentally, no ... but certain layers, yes.

“As a scholar, I have found that the internet hasn’t really done anything that wasn’t already in place before,” said Dr. Campbell with a laugh. “There’s nothing completely new under the sun. I think the patterns are always the same, but what it looks like and how it manifests is different. Us humans, we want culture, we want community, we want rituals, we want boundaries. So we always navigate to those things even though they look differently."

It is unlikely that humankind will cease needing to belong, nor to make sense of the world and of humanity. Changes are channels through which we interact with other believers and faith modders.

Dr. Campbell says the internet and technology were once only supplements to religious practices, not substitutes ... but this is drastically changing. Online spaces have become a starting point for most people: They first meet and commune online, and only after, eventually, meet offline. A whole religious experience, from initiation to the realisation of complex ceremonies, can now happen fully via smartphone or on a computer.

“That’s the only thing I think is really new. What’s going to come out of that in the next decade or two, of how the online-to-offline orientation [occurs], will be interesting,” says Dr. Campbell.

It remains a common idea that technology subverts the need for religion. But considering the number of followers religious social media accounts gather, and the degree to which religion remains central to many online conversations, it instead seems that tech and religion simply put one another’s adaptive skills to the test.

Watch them deploy an array of shapes and colours in the coming years, and enjoy the show.

"The Pit," Game Over, Dan Hernandez.

14 Oct 2021

-

Nathalie Béchet

All artwork comes from the various exhibits of Dan Hernandez, associate professor of the University of Toledo's art department. His paintings explore the visual dialogue between religion, mythology, and pop culture, including digital offerings like gaming. He is represented by Kim Foster Gallery in New York City, and Galeria Meraki in Ponte de Sor, Portugal.

DATA-DRIVEN TECH & SOCIAL TRENDS. DISCOVERED WEEKLY. DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX.

02/03

Related Insights

03/03

L’Atelier is a data intelligence company based in Paris.

We use advanced machine learning and generative AI to identify emerging technologies and analyse their impact on countries, companies, and capital.