Valley of the uncanny dolls: Sex tech and the evolution of intimacy

TOPICS

Community ShiftsRegardless of whom you prefer, Johnny and Harmony were made for you ... and if you want, you could have both.

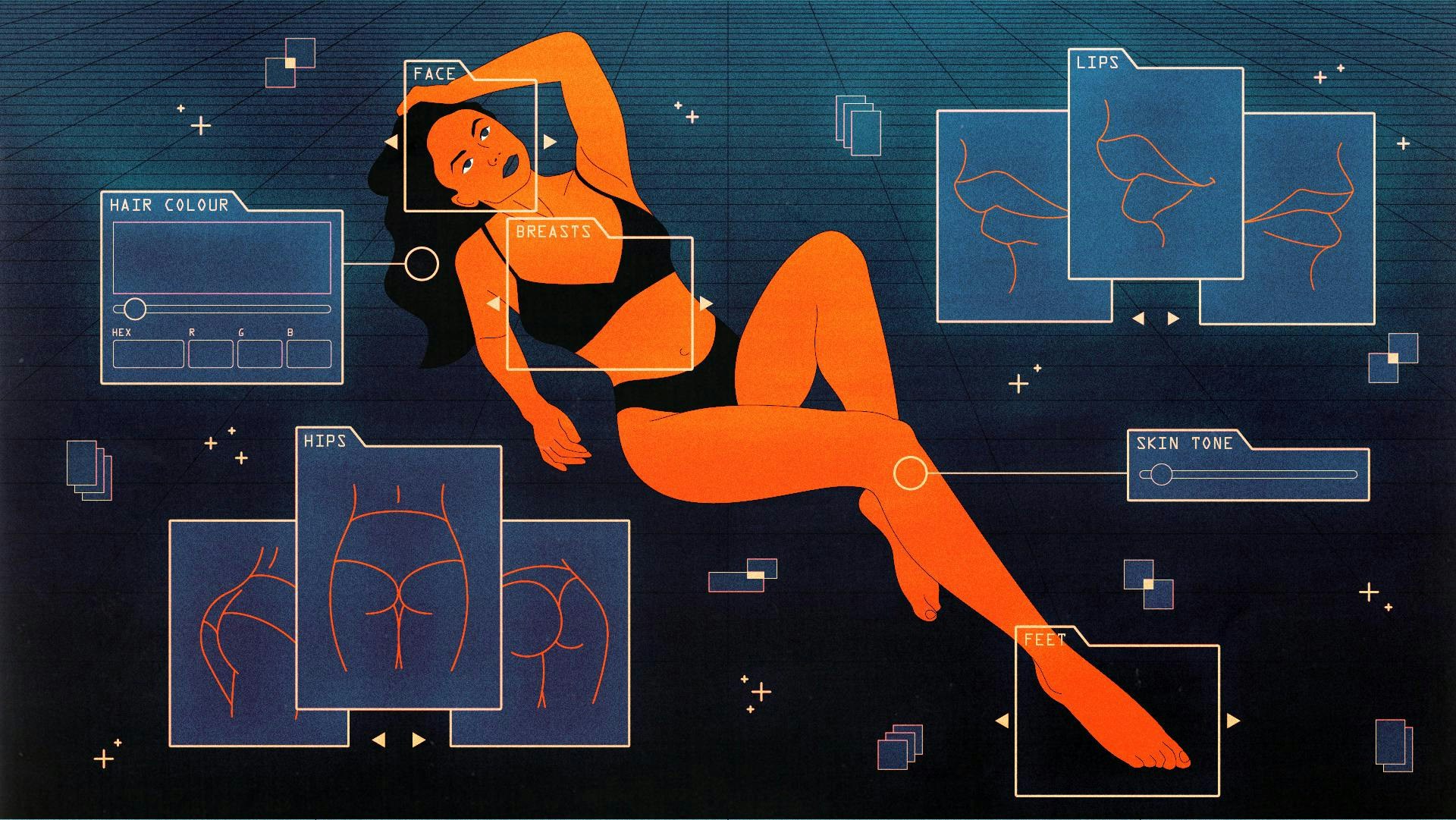

Like the children’s store Build-A-Bear, California-based RealDoll offers customisable AI and non-AI companionship dolls—like those mentioned above—from $5.999 for those seeking a male, female, or transgender experience. Choose facial features, body type, skin tone, eye colour, genital and pubic hair configurations. The AI-enabled RealDollX, with blinking eyes and luscious lips, learns about you over time; meanwhile, you control its face, personality, voice, arousal, and even orgasms.

If the dolls are too pricey, the RealGirl App offers custom virtual girlfriends that “listen, remember, and talk naturally like a living person.”

Doll manufacturer Abyss Creations, LLC has produced lifelike sex/companionship dolls since 1996, when they existed as a veiled subculture. Their predecessors were mostly static silicon women, mainstreamised by the 2002 BBC documentary “Guys and Dolls,” which explored the relationships owners cultivate with them, often beyond sexual gratification.

14 years later, dolls like TashaMarie have become Instagram influencers. Photographing them can lead to coveted spots in CoverDoll magazine.

Earlier iterations helped owners with dating anxiety and loneliness, and spiced up sexualities. And while RealDollX’s AI components are nascent, they represent a new realm of companionship. Cyborgs could become preferred substitutes for humans, uncoiling us from evolutionary mating rituals … thus transforming Masahiro Mori’s “uncanny valley” to “valley of the uncanny dolls.”

RealDoll’s CEO Matt McMullen likens the dolls to pets, or “someone that you feel cares about you.” Most owners don't mind that current versions are unlikely to pass the Turing Test, a method for determining whether a computer can pass for a human. Analysing Realbotix (the company developing AI and other tech components of RealDoll) customers, Dr. Kate Devlin—a computer scientist, and author of Turned On: Science, Sex, and Robots—found they are not mere sex objects but companions, despite their early AI maturity. Her research examines how RealDoll marketing favours romantic semantics over sexual language.

In the 2001 Steven Speilberg blockbuster, A.I. Artificial Intelligence, Jude Law plays Gigolo Joe, a humanoid robot designed to pleasure female clients: “Once you’ve had a lover robot, you’ll never have a real man again.” In the film, AI robots are equipped with machine enhancements unmatchable by human touch.

Now, brothels like Lumidolls—located in Russia, Italy, Japan, and Spain—allow clients to purchase companion doll experiences by the hour. Sex workers are concerned they could overtake the profession.

Sex tech is a growing $30 billion industry. The Future of Sex Report, which examines it from five of sexual ethicist Neil McArthur’s “wave 2” categories—augmentation, virtual, remote, robots and immersive—estimates that, by 2045, one in 10 young adults will have had sex with a humanoid robot. Long-distance sex will be facilitated by haptic suits and partner-controlled toys, 3D-printed custom sex objects, and touchable holographic lovers. With neuroscience, even emotional transmission could be possible.

Gigolo Joe gets personal in the film A.I. Artificial Intelligence.

Scientific drivers behind sex tech

Human sexuality is a biological cocktail of desire, evolutionary instincts, societal archetypes, and creativity. Advancements in sex tech, ranging from specific arousal functions to sensations of companionship, will have profound effects on sexuality and evolution.

Humans are equipped with genes that impact how deeply we connect. According to Dr. Christy Williamson of the Nutritional Genomics Institute, the hormones serotonin and oxytocin control how we fall and stay in love, and our capacity for empathy. Low levels of either results in less “pair bonding,” more social isolation, and less empathy.

“At the gene level, oxytocin is regulated by the oxytocin receptor OXTR and what has been dubbed the ‘social gene’, CD38,” says Williamson.

CD38 activity releases oxytocin, enhancing empathy and social communication. For example, those with the “T” allele at rs3796863 release more oxytocin, but the “GG” genotype is more sensitive to oxytocin, yielding an ability to cultivate better relationships. “T” allele carriers are considered poor communicators, thus less social. They may isolate and opt for digital relationships, while “GG” genotypes are more likely to pair-bond.

“Oxytocin and empathy play a strong evolutionary role in our development as oxytocin is the hormone that [is released when a baby cries, when direct eye contact is made between two people, and that ‘lets down’ mother’s milk],” Williamson explains. “Empathy is what determines how altruistic humans are, thus how we function in societies. If we lack empathy, then we not only disconnect from our most intimate relationships, but also from greater connections as a whole. Those with lower levels of oxytocin theoretically would be more likely to prefer VR partners, sex dolls and disconnected relationships.”

David Buss, founder of Evolutionary Psychology and Buss Lab at The University of Texas at Austin, reinforces this: How we use sex tech could in part be due to the evolution of mating.

For 12.000 years, patriarchal societies have dictated living standards and subjected women to them. While the fight for gender equality is far from new, movements favouring it worldwide over the last two generations have left men grappling with feelings of irrelevance as providers and protectors. The gravitation toward submissive dolls and holograms reflect a nostalgia for a past where male dominance appears unquestioned to modern eyes.

“Men evolved an attraction to women who possess cues to fertility: clear, smooth skin, symmetrical features and cues to controllability like docile and submissive qualities,” says Buss. “Women do not prioritise physical appearance as often as men do in the mating arena, rather finding success by securing a relationship investment over the long-term in addition to a potential partner’s availability and willingness to provide resources.”

In some ways, sex tech advancements resemble byproducts of gender equality efforts among those who identify as men and women. Industry expert Bryony Cole observes that female sex tech centres around investigating sexual expression in women's bodies and environments. They seek auditory or storied experiences—Dipsea’s erotic audio vignettes, experiential AR and VR, and orgasm exploration.

Bryony Cole on the state of sex tech, 2020.

The pornography highway

In Your Brain on Porn (2014), author Gary Wilson calls porn “artificial sexual stimulation.” It offers levels of sexual novelty unlike any seen in human history, tricking our minds (and bodies) into believing we experienced things we haven’t. This triggers our brain’s reward systems, which incidentally makes internet porn addictions difficult to shake. (He offers a website for those seeking help.)

But porn preferences also underline gender differences in sex tech use, observes Buss. Men generally forego plotlines for graphic sex with willing, controllable women; women prefer more context and plot development, similar to, as he refers to them, “‘ripping bodice’ romance novels where the central character seeks a successful high-status love interest for a relationship.”

A 2008 study on pornography confirmed this: Men prefer stimuli that allow objectification of the actor and projection of themselves into the scenario. When watching man-created films with no foreplay and a focus on intercourse, women reported more negative emotions—aversion, guilt, and shame—versus with woman-created films, where nearly half was foreplay.

“On a basic level, this goes back to our amygdala, our lizard brain,” says Williamson. “Given this information, the augmented reality, erotic audio, and use of dildonics that may be controlled by even a perceived other participant can all the sudden seem very erotic. Likewise, for men, having a submissive woman or doll to have intercourse or oral sex with or even a holographic experience is just as erotic.”

All this may prime us to dissociate intimacy or satisfaction from human touch. In a 2019 essay, McArthur argues that innovations like AI robots, erotic VR, and haptic feedback devices (teledildonics) are ushering in a new identity: “Digisexuality,” people who see technology as integral to their sexual selves, sometimes reducing the need for human partners altogether.

McArthur divides this into two waves: “Mediating technologies,” like web camming and social media dating; and immersive successors, like XR experiences and robots.

McArthur postulates that future sex bots will make people happier, acting as solutions to the sexual deprivation that can affect long-term relationships. Thus their development should “not just be tolerated, but actively encouraged.”

Japan: The future of sex?

Sex tech is on the rise in Japan as young women enter the workforce and enjoy increased economic freedom. They forego marriage, having witnessed the marital dynamics that would leave them bearing the brunt of housework and childcare. In Tokyo, services offer boyfriends and girlfriends on-demand for cuddling and outings, including a handsome “weeping boy” who accompanies women in crying therapy.

Many replace traditional dating with simulation games, like Voltage Inc.’s Otome Romance story apps. The company also offers “Let’s Snuggle!”, a popular AR boyfriend experience; and the VR game “Intimate Eisuki”—a masochist fantasy simulation of a young woman who is auctioned to a wealthy man.

Japan’s National Institute of Population and Social Security research revealed in 2016 that 70 percent of unmarried men, and 60 percent of women between ages 18-34, were not in relationships with the opposite sex. In 2019, public health experts at the University of Tokyo analysed national fertility survey data, finding Japan leads a global trend in decreased sexual experiences.

One in 10 Japanese adults in their 30s had no heterosexual experience, a rising trend in those aged 18-39. While the reasons are complex, virtual sex and porn consumption are implicated.

On Nov. 4, 2018, Kondo Akihiko married a vocaloid hologram, Hatsune Miku. The unofficial but lavish Tokyo ceremony included 39 friends and family, and cost $19.000. Contained in a cylinder about 18 inches tall, the 2D Miku is a popular, girlish anime character with long blue pigtails. Unable to process long strings of words, she clasps her hands and leaps vivaciously when responding to questions.

Bloomberg explores Japan’s virtual partners.

Akihiko belongs to a growing category of “fictosexual” men. He told Asian Boss media that he “loves and sees her as a real person,” and after playing dating simulation games, does not see real women as love interests. Instead, he hopes technological improvements will enhance interactions with his wife—photorealistic virtual worlds to allow them to enact fantasies, or even a Miku AI doll.

Miku’s hologram was manufactured by Gatebox, a Tokyo-based company that makes virtual girlfriends like Hikari Azuma, a “wife of the future” designed to provide emotional support. Azuma calibrates to routines, chats with you via smartphone while you’re out, and is there when you come home—a relic of the submissive female housewife, contrasting with modern Japanese women. By 2018, the company issued 3.700 marriage certificates for such “cross dimensional” marriages.

Japan is considered both an early case study and cautionary tale of diminishing human coupling, exacerbated by technology and the difficulty of achieving work/life balance. Robert Brooks, an evolutionary biologist and University of New South Wales - Sydney Professor, sees the country as a best-case scenario for sex tech, and a glimpse of relationships to come.

Brooks authored Artificial Intimacy: Virtual Friends, Digital Lovers, and Algorithmic Matchmakers. It combines an understanding of core human traits from evolutionary biology, with analysis of how cultural, economic, and technological contexts shape how people express them, including how artificial intelligence can learn and exploit social needs.

“Japan is the furthest along in a place that experienced economic changes and changes in gender roles,” says Brooks. “It represents a situation where people can have their various sexual outlets, proving that we can deliver something that will ‘scratch their itch’ no matter what it is, especially anime and manga.”

In 2014, Brooks’s research group completed the BodyLab project, a “digital ecosystem” where people rate the attractiveness of bodies online. The experiment involved multiple generations of evolution, mimicking Darwinian selection (Brooks refers to it as the “Darwinian algorithm sophisticated equivalent to A/B testing”). While traditional evolutionary measures of women's bodies have favored waist-to-hip ratios, the project explored other dimensions over which body preferences could evolve for both genders.

In their findings, the average body model became more slender after each "generation"; legs and arms evolved to be longer. Certain "mutations" allowed bodies to evolve from developmental constraints, uncovering more than one way to make an attractive body.

“The experiment turned out to be a confrontation of the varied things people are looking for, similar to what we are seeing with attractions to anime, manga, or hentai, which feature characters in varied forms that converge on a few stylised types of fantasy,” says Brooks. “What many are seeing in a partner may not actually be a lover or a partner, but a domestic goddess type or other stereotype.”

Dangerous liaisons and vengeful technology

In his 1997 book Why Things Bite Back: Technology and the Revenge of Unintended Consequences, historian Edward Tenner argues that new technologies have inadvertent “revenge” effects that counter their solutions, partly due to societal problems that existed before the technology arrived.

Sex tech is a multifaceted constellation, impacted by biological, genetic, psychological, and societal and political forces. Unintended consequences are difficult to pinpoint, since our predictions were formed in a reality where they were not prevalent. Humans are also notoriously unreliable at making solid assessments of how technological adoption will alter our reality. Thus, is it possible to regulate for certain issues based on assumptions? If we wait, will it be too late?

In the 1993 film Demolition Man, Sandra Bullock promotes VR-based sex as a deterrent to “bodily fluid transfer.” In the sterile world of Bullock’s character, procreation is done in a lab, and human contamination of any kind is anathema——less shocking today, given the Covid-19 crisis.

Likewise, advocates of sex tech argue it can help sustain relationships without physical contact, unwanted pregnancies, transmissible diseases, or risks to personal security. As McArthur observed, it also helps with social anxiety and loneliness. But these same benefits could limit psychological, biological, and genetic evolution.

Jenny Kleeman, author of Sex Robots and Vegan Meat, sees sex tech as an attempt to control and circumvent uncertain circumstances—the natural, potentially beneficial, struggles with relationship formation. “Real power comes from willingness to reform our behaviour,” Kleeman told Futures podcast. She added:

“When we outsource fundamental aspects of human existence for the illusion of control over our nature, we disempower ourselves. The real power lies in the courage to change our mindset.”

Kleeman says companion dolls provide “illusory companionship,” likening them to slaves—relationships where only half of the partnership’s desires matter, which could eventually erode the human partner’s capacity for empathy, since we edit ourselves based on others’ behavioural responses.

This invites comparison to the Nash Equilibrium’s “prisoner’s dilemma,” or B.F. Skinner’s variable ratio reinforcement behaviours, which appear in swipe-right-or-left dating apps: The perceived availability of endless mates encourages continued play, making us unwilling to address complications in new pairings.

Buss says men using companion dolls likely won't gain the relationship and mating experience necessary to mature and grow emotionally. “Some men may lack the motivation to overcome their anxiety and develop appropriate social and relationship skills. Once these new technologies become more prevalent, we will definitely need scientific studies to determine the harms they can create as well as the benefits they provide,” he says.

Nevertheless, machines will get better at exploiting emotions via AI and algorithms. It remains to be seen how society adapts. Looking ahead, Brooks views sex tech’s future through two primary dimensions: How we like to make love, and who controls our data.

“Societal responses tend to fall into a few categories, from extreme to laissez-faire,” says Brooks. “From The Handmaid’s Tale dystopia with sexual repression and central control, reflecting much of what we see in today’s Boko Haram or ISIS. Another version is seen in corporate power and corporate control over information similar to current tech companies. There is also a Westworld view of chaos with unrestricted people doing nasty things to each other and to robots. Finally, like the movie Her—relaxed and easygoing sexuality becomes enhanced by sex tech.”

27 Jan 2022

-

Jessica Buchleitner

Illustration by Debarpan Das.

DATA-DRIVEN TECH & SOCIAL TRENDS. DISCOVERED WEEKLY. DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX.

02/03

Related Insights

03/03

L’Atelier is a data intelligence company based in Paris.

We use advanced machine learning and generative AI to identify emerging technologies and analyse their impact on countries, companies, and capital.