Chasing a mirage? The social media authenticity movement

TOPICS

Social MediaGeneration Z—those born between the mid-1990s and mid-2000s—is increasingly deserting Facebook.

They game Instagram by creating “fake” private accounts (“finstas”), using them to share unstaged and goofy pictures for close friends. WGSN, a trend forecasting company, observes that “influencers” are no longer their go-to. They instead favour “Genuinfluencers,” creators who promote information, advice and passions rather than products.

This growing disenchantment is echoed by studies about social media use and wellbeing.

A 2014 survey led by a UK charity found that amongst 18-34 year olds, close to 50 percent admitted that social media made them feel ugly or unattractive. 30 percent said it made them feel lonely. Another recent survey found that 41 percent of 18-24 year-olds say social apps make them feel sad, anxious, or depressed. 64 percent take regular breaks from it.

A 2021 questionnaire, led by L’Atelier on 19- to 23-year-olds, seems to confirm this. Respondents divulged diverse concerns about social media, from addiction to privacy issues. They also expressed frustration about being spammed by ads, overwhelmed by endless feeds, or pressured by social norms and beauty standards.

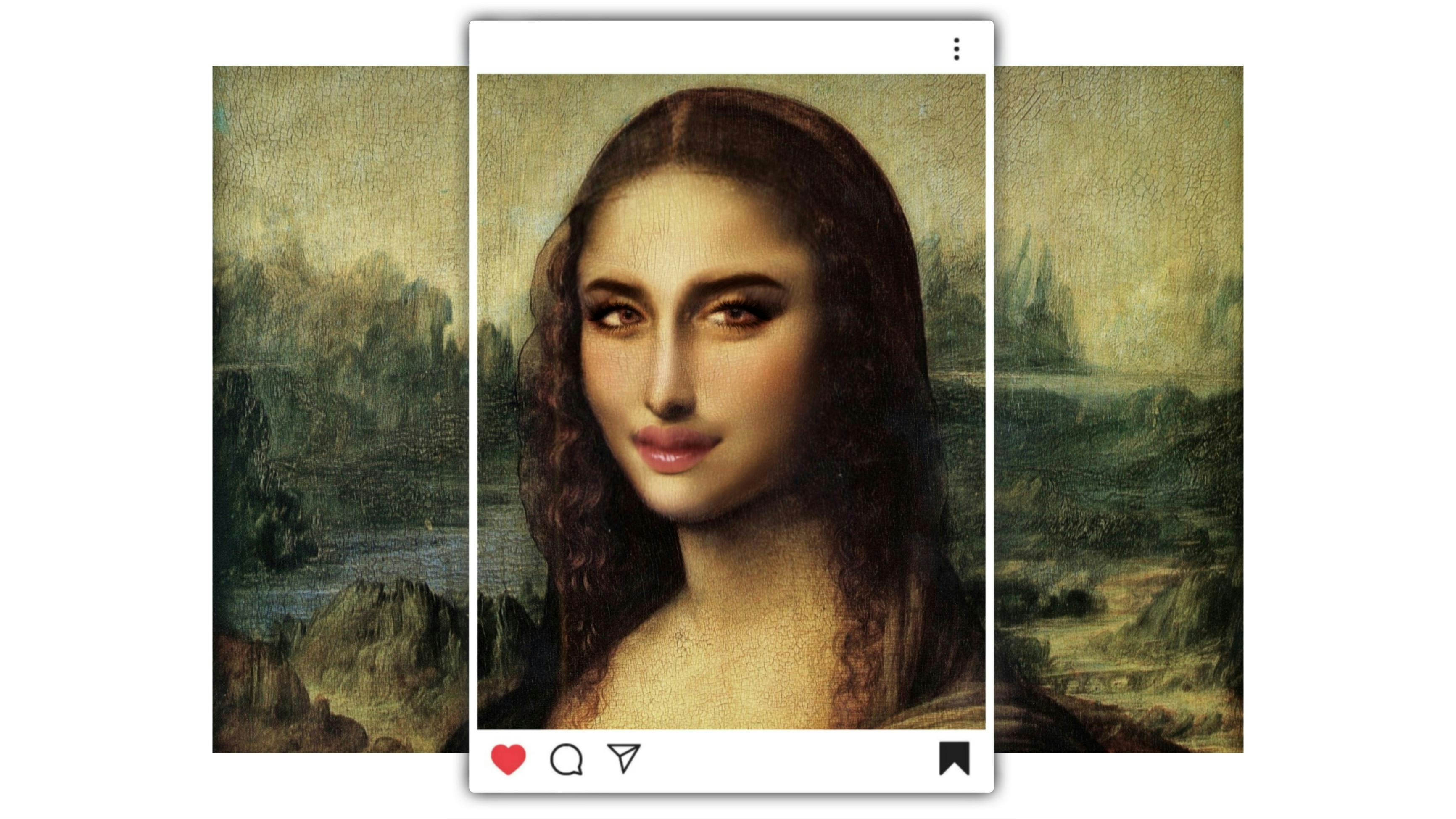

Calling out artifice: half-hearted at best

Behind-the-scenes or whistleblower accounts, and photo challenges designed to make civic denunciations, have gained attention on Instagram and TikTok. They are meant to remind users that “social media is not real life.” Instagram account CelebFace exposes celebrity photo edits and surgeries. Then there are user-launched challenges like “Instagram vs. reality,” “me, also me” and “posed vs. relaxed.” Certain influencers have even made these types of juxtapositions a signature: Danae Mercer and Rianne Meijer, for example, act as emissaries of this liberation movement.

These endeavours revolve around the ideal of an artifice-free environment (as opposed to one where the artifice mounts ever higher, and bleeds into offline life). But their core intents can grow cloudy with time. Often these challenges reproduce social validation mechanisms, rather than pinpointing duplicity or demonstrating true lived experience.

Jessica Sprengle, a therapist who specialises in eating disorders, says this exhibition of so-called flaws—such as cellulite or belly rolls—is a form of body-checking, a symptom of body dysmorphic disorder (BDD).

And these posts feel disingenuous when used by people who are clearly not trying to combat pressure for perfection. Laura Benwell pinpoints influencers who use the hashtag #InstagramvsReality for pictures of attractively tousled hair, or staged goofiness. These misappropriations of well-intentioned movements fuel BDD by creating even less achievable standards: “Flawed selves” that are closer to conventional beauty than what most people consider their “best selves.”

The catfish challenge on TikTok is another illustration of repurposing gone wrong. The goal was initially to expose highly edited and glammed-up pictures of oneself, but some users have turned it into an opportunity to shine: They first appear disgracefully disguised (fake pimples, messy hair, ragged clothes), then pair them with glamorous makeovers of themselves. Thus, instead of underlining the problematic behaviour of catfishing, they instead feel more like “glow-ups”—staged ugly-duckling to beautiful-swan juxtapositions one might find in a film like The Princess Diaries.

These clunky, or outright dishonest, social media trends are a disappointment to younger users. In an interview with L’Atelier, 20-year-old Zoe said, “What I like the least about Instagram is its superficiality, the fact that everyone is putting on their best self. Obviously, this does not reflect reality.”

This partly explains the rise in quests for more authenticity, and the emergence of “anti-social” social apps.

Anti-social, anti-filter, anti-metric

BeReal is a free app that was created in January 2020. The social network—which grew from 10.000 daily active users in March 2021, to 400.000 in June 2021—claims to be “a new and unique way to discover who your friends really are in their daily life.” Users say “what’s your BeReal?” is the new “what’s your Snapchat?”, or claim that, since BeReal, they no longer post on Instagram.

In its marketing, BeReal makes a distinction between “realness” and “authenticity.” It functions by alerting users at random times, then gives them two minutes to take a photo, blocking filters or any other attempts at artifice.

“It's the closest to reality a social app can get,” one user tweeted. And it capitalises on instantaneity or spontaneity, terms often used by our interviewees. Zoe wrote: “What I like the most about BeReal, unlike Instagram, is its realism because the shot captures the present moment, filter-less, edit-less.”

Another emerging social network is Junto, a “new breed of social media founded to rebalance our relationship with technology.” Junto uses a form of blockchain called Holochain. It has neither vanity metrics (such as Likes) nor advertisements.

Similar to BeReal, which disables access to friends’ pictures if you haven’t posted yours, Dispo—launched in February 2021—lets you take pictures that are only visible from 9am the next day. Dispo calls itself a “social media app that lets you *live in the moment*”.

Is that refrain starting to sound familiar?

Minutiae is more of an art project than a social platform. Like BeReal, it notifies you at random times of day, and provides one minute to take a photo. To manifest the notion that a day contains just 1.440 minutes, it has users take a photo a day for four years, then prints them in an album. Like its peers, Minutiae labels itself an “anonymous anti-social media app with no profiles, no likes, no comments.”

For emerging networks, it’s clearly important to make a distinction from mainstream contenders (Minutiae goes so far as to call itself “the anti-Instagram”), illustrating a shift in values to the “pure” or unaltered.

One user’s five-star review of Minutiae reads, “The pictures you end up taking are raw and authentic because it’s in the here and now. There’s no crowd you’re trying to impress, so there’s no pressure for the perfect aesthetic like there is in most other photo-based apps.”

These more “authentic” social media apps are characterised by particular features: A selective circle of friends and followers, instantaneity, the inability to stage and edit pictures, and a curated sense of dependence.

Time scarcity issues

BeReal, Dispo and Minutiae notify users when to take pictures and/or when to look at them. Some find this functionality invasive.

A series of user tweets recount the delicate situations BeReal has unintentionally placed them in. They report receiving notifications during exams, for example, and feeling pressured to take a picture anyway; or, likewise, getting notified in the shower or while asleep.

The narrow time window required to take a photo has also created tensions. This feature builds on the assumption that people's phone are with them all day, and it can be punitive: Missing your shot today means you won’t be allowed to see those of friends: “You are obliged to post to access other users’ content,” said 23-year-old Sebastian. This is a constraint for those who use social media to feel connected to a community.

To discourage compulsive scrolling, Minutiae restricts the ability to view others’ profiles to just a minute a day. And because Dispo hides pictures until 9am the next day, it arguably compels people to rush to their phones the moment they wake up—a behaviour many actually try to avoid.

What even is authenticity?

Certainly these influencers and apps capitalise on authenticity. But they are not entirely devoid of sense or purpose. As Anthony Kelly observed in our work on digital selves, it is difficult to gauge who influences who when it comes to social media. The “authenticity” business strategy also stems from a clear, pressing need for healthier ways to engage with social media, especially for younger people.

A signal is being sent. It ought to be heard.

Authenticity is often used in marketing as a benchmark for evaluating success. Anthropologist Saskia Cousin, who specialises in tourism, defines authenticity as an analytical tool that helps people assess the native quality and/ or original character of a location, piece of work, or situation.

Many parallels can be drawn here. The quest for a more authentic travel destination “can be considered a way to escape alienation by looking for a behind-the-scenes, but this endeavor can only fail, since the very presence of tourists implies the setting of a fabricated behind-the-scenes that then becomes the new front scene,” Cousin writes. The same paradox applies to social media.

Apps like BeReal or Minutiae are “authentic” as long as they are niche. Once they gain notoriety, they fall from grace, often because they are purchased by established entities (such as Instagram), or because they must eventually respond to market growth pressures. As 19 year-old Lucas noted, “The risk could be intrinsic to popularity; spontaneity might lack over time, once the app is established as a big one. It would become mainstream and thus less convivial.”

Interestingly, here “mainstream” is treated as a state in natural opposition to “authenticity.”

Finally, photography-based apps, no matter their intent, still require an anthropic selection of images and a theatricality of the self. Kelly and I observed how people often fantasise about virtuous figures who only share their “true selves” online, but such a person does not exist; social interactivity, and photography, demand stagings of self by their very design.

And that is fine.

Changes loading…

All this being said, there are drastic changes ahead worth unpacking.

The TikTok and Instagram challenges mentioned here resulted in a large body positivity movement that fosters more inclusivity. Hashtags like #normalizenormalbodies or #bodyneutrality distill a demand from younger people for more relatable bodies, and more relatable platforms to exhibit them. More non-influencers openly share pictures of stretch marks, scars, cellulite, acne, belly rolls, body hair, amputated limbs, depigmented skin, and more.

Some people report being empowered by the sense that these are not imperfections but mere bodily variations. 21 year-old Lisa observed, “They [social media] fill in my boredom and I’m a bit too addicted unfortunately. Despite all that, posting pictures of myself helped me get to love my physical appearance more.”

By and large, it appears that Generation Z doesn’t want to have to cater to unrealistic beauty standards on social media, and is not interested in sustaining the algorithms and metrics that create pressure to achieve them.

“Anti-social” social apps are an early market attempt to facilitate that sentiment by challenging traditional networks—a warning that if they don’t change their models, they may find themselves deserted by younger users.

Instagram’s decision to hide the number of Likes on photos shows that these acts, at scale, can impact supposedly immutable tech giants.

It’s unlikely that Instagram, Facebook and TikTok will "die" any time soon (though, in Facebook’s case, an antitrust complaint launched by the FTC may challenge its grip). BeReal, Dispo and Junto might never truly take off; surely people will want to edit at least some pictures, sometimes, for consumption.

But this is not about that. It is about a new generation lobbying, in its own way, for the idea that the networks we use for pleasure should align with our values, instead of bending us to theirs. This conviction is so powerful that it may yield significant change.

The 2020s may well be the right decade to start asking, what do we actually want from social media? And how can we design social communities that offer us more than they take away?

21 Nov 2021

-

Nathalie Béchet

Image by author. Special thanks to L'Atelier intern Olivier Lhuissier, whose research and interview findings supported this work.

DATA-DRIVEN TRENDS DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX WEEKLY.

02/03

Related Insights

03/03

L’Atelier is a data intelligence company based in Paris.

We use advanced machine learning and generative AI to identify emerging technologies and analyse their impact on countries, companies, and capital.