Ectogenesis: Could this be humanity’s next small step?

Like many things on Twitter, it started as banter.

In a January 2022 exchange between Elon Musk, Gumroad founder Sahil Lavingia, and Ethereum co-founder Vitalik Buterin, Musk commented on declining US and global fertility rates. In response, Lavingia proposed “investing in technology that makes having kids much faster/easier/cheaper/more accessible in the form of synthetic wombs,” ostensibly to stem global population collapse overall.

Buterin chimed in on the idea’s merits, citing the earnings disparities women experience after having children. “Synthetic wombs” could remove the “high burden” of pregnancy while reducing inequality, he observed.

It got weirder. For Musk, they mused, artificial wombs would produce ideal colonists for Mars. People could be genetically engineered for the red planet’s harsh conditions, a concept popularised by Evie Kendall in 2021. In “Ectogenesis for Space Exploration,” Kendall argued ectogenesis—growing an organism in an out-of-body, artificial environment—can “[reduce] the risks and burdens to female settlers and avoid losing members of the early settlement workforce to maternal morbidity and mortality.”

At the time, this conversation between founders was seen as typical of how “tech bros” consider technological solutions for socioeconomic disparities while ignoring the reasons for their existence.

Dystopian consequences often spring from similar inductive leaps. Most begin with tech optimism: a compulsion to throw technology at social ills. In Why Things Bite Back: Technology and the Revenge of Unintended Consequences, historian Edward Tenner argues that new technologies have inadvertent “revenge” effects that counter solutions, partly due to preexisting societal problems. In The Laws of Human Nature, Robert Greene highlights the likelihood of such unintended outcomes in Law 6: Shortsightedness. Humans are impressed by observations made in the present. In tech terms, this manifests as an infatuation with innovation that never fully develops an holistic view of surrounding influences and potential consequences.

Current reproductive technologies, predecessors to the artificial womb, follow this pattern. Created to ease struggles with fertility and gestation, they’ve become means to circumvent the “disadvantages” of pregnancy related to class, income, and norms.

Biological challenges to birth and conception

Modern ectogenesis technologies proffer humanitarian narratives: Inventors illustrate their potential to save premature babies, or aid struggling mothers with conception.

Premature birth affects over 1 in 10 babies globally. According to the World Health Organization, one million out of 15 million premature infants dies shortly after birth each year. Many survivors suffer lifelong physical, neurological, or educational disabilities.

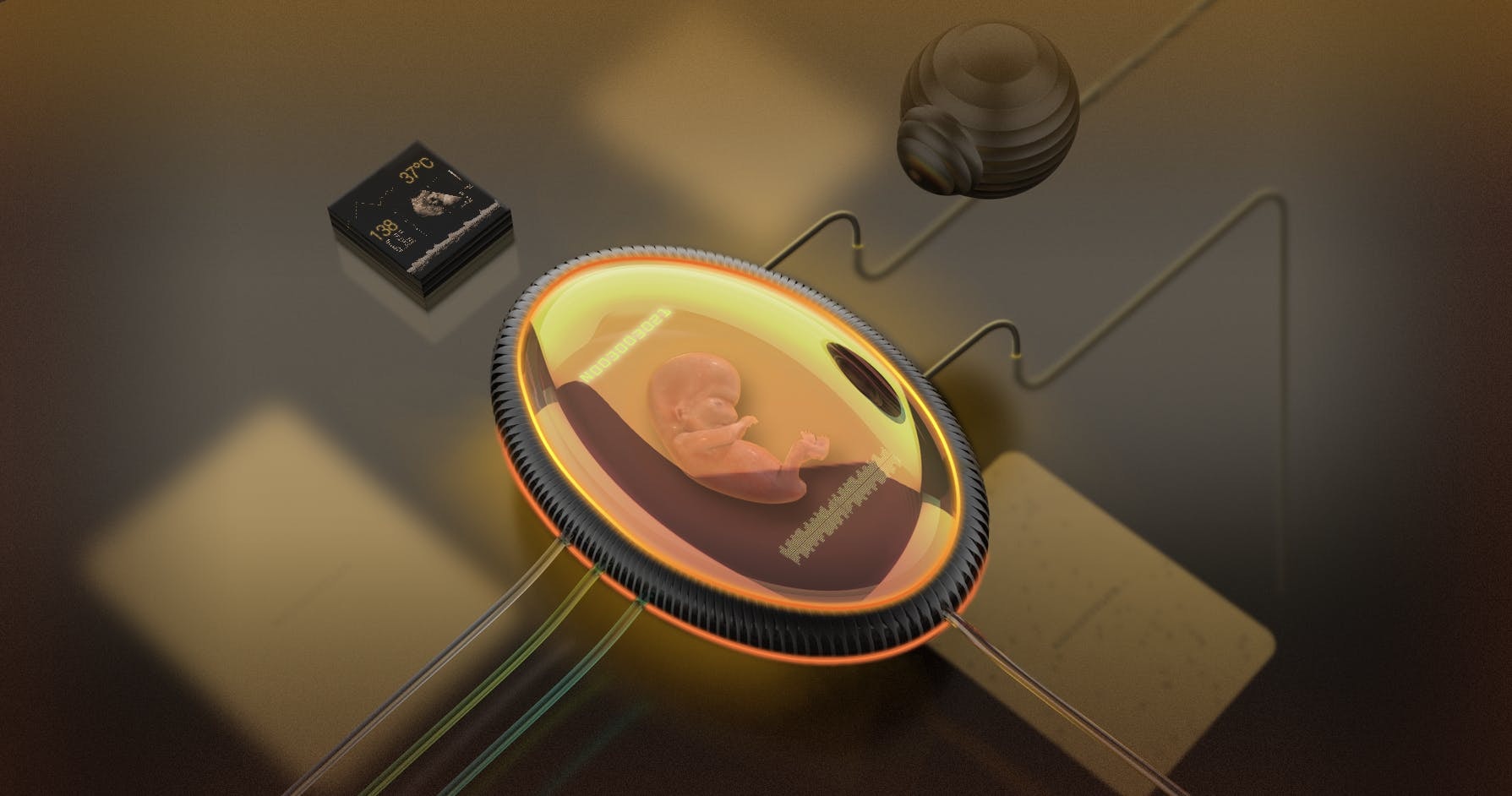

Human foetuses require 37 weeks inside a mother’s uterus to fully develop while submerged in amniotic fluid. When born preterm (before 37 weeks), they’re often placed in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) for heart and lung support. Air exposure can lead to complications in the heart, lungs, and vital organs. Assuming conception is possible, an environment mimicking the womb, similar to current partial ectogenesis devices, is ideal.

Then there is the matter of conception. 48,5 million couples experience infertility worldwide, defined as the inability to get pregnant after frequent, unprotected sex for one year. In western societies, this leaves two tech-driven options: In-vitro fertilisation (IVF), where mature eggs are retrieved from ovaries, then fertilised by sperm in a lab before transfer to a uterus; or surrogacy, where another woman gestates a fertilised egg, either her own or one implanted via IVF. Both afford women a pregnancy life extension.

Another mother

Surrogacy has existed since antiquity, when women bore children for nobles, clans, or societies. In the biblical book of Genesis, Abraham and Sarah used a servant, Hagar, to carry their child Ishmael. As in Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, using domestic help for gestation was a common solution among childless wives.

Today, laws exist to protect surrogates. The first legal surrogacy agreement, drafted in 1976, permitted no monetary compensation. Surrogacy became big business after 1980, when Elizabeth Kane, the first legally compensated surrogate in the US, was paid $11.500. In 1978, Louise Brown became the first baby born via IVF, ushering in a game-changing notion: Conception no longer required sex. 1982 saw the first baby born via commercial egg donation. In the infamous 1985 “Baby M” case, a surrogate mother fought for child custody.

The American Society of Reproductive Medicine suggests that “gestational carriers”—a woman who agrees to have a couple’s fertilised egg (embryo) implanted in her uterus—should only be solicited for medical reasons. In most European countries, surrogacy is prohibited, with specific regard to commercial surrogacy, as evidenced by this 2013 EU study. In December 2015, European Parliament condemned all forms of surrogacy, arguing it undermines human dignity.

Recent breakthroughs

Advancements and dystopian imaginings aside, we remain decades away from full ectogenesis. Current research primarily focuses on partial ectogenesis, where a foetus is grown in a womb, then removed and incubated. This is mostly due to ethical guidelines observed by 17 countries, suggesting scientists halt research on foetuses before they develop vital organs at 14 days.

In 2021, however, the International Society for Stem Cell Research relaxed these guidelines, proposing case-by-case review. Venture capital funding for fertility startups increased between 2017-2020, with global investments rising to $176 million by October 2021.

The last 30 years yielded vast developments in the field, none close to ubiquitous use. In 1996, Juntendo University researchers introduced partial ectogenesis, placing goat foetuses in artificial amniotic fluid; in 2003, Cornell University’s Dr. Helen Hung-Ching Liu grew a mouse embryo in an artificial womb. In 2011 she used one to sustain a human embryo for ten days, then terminated it due to the 14-day ethical rule.

In 2017, when Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) placed a premature lamb foetus in an artificial biobag womb for 28 days, it began growing a wool coat. Its research and prototypes are described in a 2017 Nature Communications paper, followed by a 2021 patent (related provisional applications were filed in 2015). The device claims to reduce mortality and disability for extremely premature babies by mimicking the prenatal environment. This biobag is closest to mirroring science fiction adaptations, and could provide a novelty for parents wanting to witness the stages of foetus development. There have been no additional publications about the device since. CHOP declined to comment for this article.

In 2013, Western Australia’s Women and Infants Research Foundation (WIRF) began work on Ex-Vivo Uterine Environment (EVE) therapy; by 2017 an artificial womb was successfully used to incubate healthy baby lambs for one week (between 21 and 24 weeks old, in human terms).

In 2019, Scientists from the Eindhoven University of Technology displayed an artistic impression of artificial womb prototypes—veiny scarlet balloons, suspended from clear strings. The team received a Future and Emerging Technologies grant of almost 3 million euros from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 programme to support their Perinatal Life Support System (PLS) project, which aims to develop a liquid-based environment similar to a womb, and postulates a complete concept in 5 years. A mannequin, and advanced clinical modelling, will mimic an infant as opposed to a lamb during testing and training.

The PLS project.

In 2021, the Weizmann Institute of Science reported success growing, for the first time, developmentally normal mouse embryos for up to eleven days inside an artificial uterus. Since mice gestate around 20 days, the experiment suggests it may be possible to develop human embryos from fertilisation to birth. In 2022, Institute researchers created the first "synthetic embryos,” bypassing the need for sperm, eggs and fertilisation. These could theoretically self-assemble into early embryo-like structures with an intestinal tract, brain components, and a beating heart. Among the benefits touted for this approach: Reducing animal experimentation, and providing cells and tissues for medical conditions.

Despite these advancements—the field itself is now as old as NASA—Matt Kemp, acting chief scientific director of WIRF, observes recurring challenges: Foetal heart issues, and infections revealed in experimentation.

“These experiments require a large human capital commitment and have needed a lot of infrastructure,” says Kemp. “Unless someone is sitting on a massive hole of data, we are far from anyone trying to use this technology responsibly. We have developed a system that allowed us to attain a sheep foetus at 23 weeks, but we don’t have any long-term data on how they would react after coming off the system. If you introduce new therapeutic technology, you must be sure it offers much better options than those currently available.”

Asked to consider whether ectogenesis devices may soon be marketable, he likened the possibility to “someone saying they will retrofit a plane and take it to the moon next week.”

“It is important to have these broad discussions around ethics,” Kemp adds. “Dystopian perspectives must be grounded in reality and about what we can conceivably do now, not what we want someone to do or assume will be done.”

Biopunk Babies, Genetic Classes

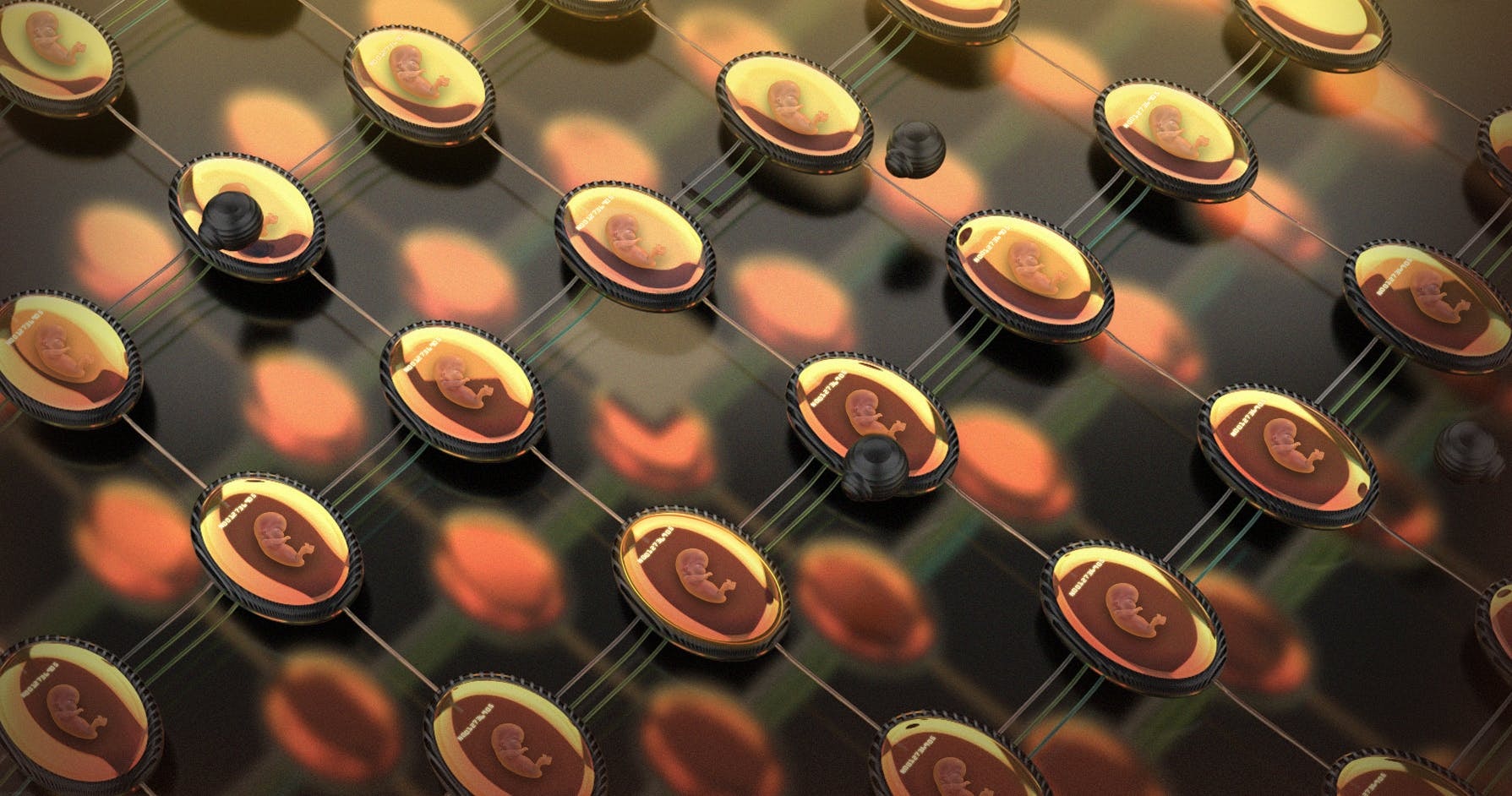

Science fiction is rife with projections about post-21st century birth. In “The Matrix,” human beings are farmed from luminescent bulbs, dangling from AI-powered stems. In Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, reproduction becomes a state function, and sex is recreational. Its fictional Central London Hatchery and Conditioning Center is a biological version of Henry Ford’s assembly line.

Beyond entertainment, these visions of childbirth and gestation distill possible futures for family planning, gender equality, and changing sexual norms. They often culminate in ectogenesis.

“Ectogenesis” was coined in 1923 by British scientist JBS Haldane, during a Cambridge University lecture involving exploratory fiction. Haldane predicted that, by 2074, only 30 percent of births would come from a human womb. In 1955, Emanuel Greenberg patented the first design of an artificial uterus, ostensibly to help premature babies develop post-birth. It included an amniotic fluid tank for gestation, a machine connected to the natural umbilical cord, blood pumps, an artificial kidney, and a water heater.

Haldane was inspired by ectogenesis’ social engineering potential—an approach praised by Adolf Hitler. His Third Reich was even more ambitious: Using eugenics to design socially acceptable, fit, and useful offspring while edging out disabilities, health issues, and undesirable racial characteristics and sexual preferences. Eugenics circulated academic circles in the late nineteenth century, when Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species appeared.

Darwinism is often interpreted as the idea that species compete for fitness, defined as biological perseverance. This became the pretext for a larger capitalist narrative: Survival of the most productive and best-revered. In “Darwinism, Dogma, and Cultural Evolution,” anthropologist CR Hallpike illustrates the issues with this dogmatic interpretation of Darwinism—which persists, despite Darwin’s insistence that “survival of the fittest” was a misinterpretation of his findings.

By introducing the possibility of “designer babies,” ethicists fear ectogenesis will act as a Trojan horse for eugenics, driving a wedge between natural and artificially conceived children. The 1997 film “Gattaca,” where offspring are genetically optimised in a futuristic society, encapsulates this anxiety: Naturally conceived children, dubbed “invalids,” become a lower social class when artificially designed offspring become the norm. To advance his career goals, the film’s protagonist—an “invalid”—illegally purchases body matter from a near-perfect counterpart who has become crippled. The latter is reduced to scraping skin flakes, or providing hair and urine samples upon request … a form of surrogacy.

“Gattaca” emerged from the sci-fi subgenre “biopunk,” exploring biotechnology’s societal impacts. While it seems like outlandish speculative fiction, predecessor birth technologies point in its direction.

Motherhood and Socioeconomics

For centuries, psychology has harboured combatting theories on gender and pregnancy. “Womb envy,” coined by psychologist Karen Horney, describes men’s innate envy of female reproductive functions, countering Freud’s “penis envy,” which theorises that young girls experience anxiety upon realising they do not have a penis.

In her 1970 philosophy classic, The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution, Shulamith Firestone argues that pregnancy subjugates women to innate biological inequality; to achieve equality, they must control reproductive choices using artificial wombs. Following Karl Marx’s theory of historical materialism, she argued that the biological division of labour in reproduction is the root cause of patriarchy, economic class exploitation, and other societal ills, since women are vulnerable during pregnancy and the lengthy childrearing years. She observes that Sigmund Freud’s descriptions of personality distortions relate to the dependency women and children have on male counterparts.

Though perceived as radical, Firestone’s theory echoes Ethereum co-founder Buterin’s sentiments at the top of this article. Socioeconomic penalties for women with children are immense. Sociologists dub their disadvantages in pay, perceived reduced competence, and career stagnation, relative to childless women, the “motherhood penalty.” Economics sees motherhood as high in “opportunity cost,” due to surrendered career advancement, lost wages, and productivity decline from unpaid care responsibilities. Several studies, notably one from 2018, reveal women without children out-earn mothers, with earnings almost equal to men in Denmark, the United States, and other industrialised nations.

While we don't immediately consider pregnancy life-threatening, preventable causes kill approximately 808 women daily, or one woman every two minutes. For every death, 20 or 30 more suffer injuries, infections, or disabilities—including incontinence, pelvic fractures, and kidney failure postpartum. There are psychological effects, like postpartum depression, or mood swings accompanying fluctuating hormones. Some women want children, but because of the physical aspects and career demands, don't want to be pregnant.

Birth technology, like surrogacy, IVF, and egg freezing, present legitimate options. Companies like Apple and Meta offer egg-freezing coverage for female employees, which critics perceive as a way to extend working life without distraction. A controversial Bloomberg magazine cover from 2014 featured a proud white (thus privileged) woman, flanked by the headline, “Freeze your Eggs, Free Your Career.” The same year, economist Claudia Goldin released a paper showing that “high reward” occupations often come with the expectation that employees log longer hours and remain on-call for competitive advancement—a relic of the Industrial Revolution. Parental leave, or caregiver time off, compromises such dedication, rendering the employee less valuable.

“The gender gap in pay would be considerably reduced and might vanish altogether if firms did not have an incentive to disproportionately reward individuals who laboured long hours and worked particular hours,” writes Goldin.

Social surrogacy, or surrogacy without a medical need, is increasingly popular among celebrities and affluent women. This is sometimes seen as a form of economic outsourcing, where affluent women benefit at the expense of less privileged women, who provide these services for money. Bioethicist Rosemary Tong says ectogenesis will likely also favour affluent and white women. Current healthcare disparities, and differences in care options offered to those able to afford them, make it unlikely to favour women in lower economic classes.

“Privileged people have access to IVF and surrogacy now, versus non-privileged. Women of colour struggle to obtain access to reproductive technologies, and that is not likely to change with ectogenesis. Universal healthcare plan coverage could standardise the practice more,” says Tong.

Then there is this worst-case scenario: Could women be subjected to using artificial wombs without consent?

This routinely occurs with cesarean sections and is debated in bioethics. Technology could also replace biological gestation entirely, due to natural pregnancy risks, especially in innovation-aggressive countries like the United States, which has among the worst infant mortality rates among OECD countries (33rd out of 36 in 2019). Pollution, chemicals, food substances, and other environmental factors affect foetus development in natural pregnancies; an artificial womb could standardise birth, ensuring optimal health. This could lead to a breakaway social class that exacerbates racial and ethnic divides in new ways.

Developers of technology determine impact, a critical point to make as reliance on birth technologies grows. In tech, representation matters, especially when tech leaders purport the belief that innovation can provide solutions to longstanding problems.

Technological innovation historically overlooks vulnerable and underrepresented groups, even when it purports to help them. To what degree will women be involved in the critical product lifecycle phases of coming birth technology—design, testing, implementation, and healthcare policymaking? In her 1993 paper “The Matthew Matilda Effect in Science,” historian Margaret Rossiter observes that women’s contributions to important scientific developments were “ignored, denied credit or otherwise dropped from sight”; their participation only scaled in the last 50 years.

Women hold one in five top jobs in science, technology, maths, and engineering globally, per the University of Michigan and the New York Stem Cell Foundation, which assessed more than 1.200 gender equality report cards in nearly 40 countries from 500+ academic and professional institutions. They found that research institutions failed to retain and promote women into positions that allowed them to carry out high-impact research.

Lack of representation also affects product development in vanguard technologies, particularly in artificial intelligence (AI). Recent studies of voice recognition technologies, trained and tested solely by men, showed struggles understanding female voices. In the recruitment process among technology firms, HR algorithms favour men’s CVs, since they most reflect their training models … as evidenced by Amazon’s discontinued AI recruiting technology.

Former Google software engineer James Damore’s controversial 2017 memo, claiming men are predisposed to functions like coding, exemplifies prevailing beliefs in tech. He argued that the “distribution of preferences and abilities of men and women differ in part due to biological causes and that these differences may explain why we don’t see equal representation of women in tech and leadership.”

With lack of representation in necessary development fields, and poor records on other sociological factors, perhaps ectogenesis should not be an inductive leap, but rather an inductive analysis of what, in society, makes pregnancy such a burden to bear. There is time to address these issues before unintended consequences appear.

“If you have a present load of cash and a serious intent to improve the situation for women, invest in proper prenatal care, proper family planning, or social programs for women and girls for now. This technology is very expensive to run and currently carries significant risk,” says Kemp.

09 Dec 2022

-

Jessica Buchleitner

Illustrations by Dominika Haas.

The future in your inbox.

02/03

Related Insights

03/03

L’Atelier is a data intelligence company based in Paris.

We use advanced machine learning and generative AI to identify emerging technologies and analyse their impact on countries, companies, and capital.