Me, myself and my avatar: Data ownership in virtual worlds

TOPICS

Data and PrivacyIf you’re reading this, perhaps it’s no surprise to you that there is a commercial and strategic value to the data we generate all day, whether online or offline.

In terms of the sheer volume of that potential, these are unprecedented times: 90 percent of existing data was generated in the last 2 years.

Last year, a survey by Insights Network found that 79 percent of respondents want compensation when their data is shared … suggesting everyday consumers are increasingly aware of the value of our breadcrumbs, and believe they have some sort of claim to it. The debate over data ownership is about to get heated.

The mutable nature of data

Precedent-defining battles about access to, and responsibility for, digital information has been limited to a small number of use cases. Overwhelmingly, we appear more than happy to exchange “our” data for “free” services.

That these services are not actually free is obvious to anyone who follows the public and private equity markets—where numbers of users, rather than revenue, drive increasingly lofty valuations. According to Tapmydata, Facebook’s users each represented around $3000 of value to the company on average in April 2021.

This phenomenon is not limited to social media or advertising. The value of our data is particularly acute in the case of genetic information; many ancestry DNA testing companies offer free, or discounted, genetic tests, in exchange for the right to share gathered data with third parties. A relevant case surrounding genetic databases lies in the development of genetic forensics. One company famously uses DNA data to sketch portraits of criminals to aid police investigations. It is hard to imagine data more intimate than the kind that allows others to reconstruct our bodies.

But perhaps we’ll lose our queasiness about this. An EU-funded project, Neurotwin, is attempting to create a digital copy of the brain, to study and predict the effects of different types of brain treatments, including for Alzheimer's disease.

Beyond diverse types of data, there are also hierarchies of personal data. Research by MacKeeper and YouGov in 2020 showed businesses were willing to pay more for Generation Z’s personal data (people currently between ages 18-24), and certain ethnic minorities. The personal data of women has on average been considered less valuable.

Given the nuanced types of data we produce—which is ultimately leveraged in the market—issues around data ownership are more urgent. This is something big data companies are beginning to feel. Notably, Facebook’s holding company, Meta, threatened to withdraw from Europe, in the event the European Commission advances with plans to limit transatlantic data transfers. Facebook opted to abandon its automatic facial recognition programme and committed to deleting all of its data. Just this year, France joined Austria in deeming Google Analytics illegal.

What is driving this change in how battle lines over data are being drawn?

Parallel identities

When Mark Zuckerberg made his now-famous announcement to rebrand Facebook as Meta, he conjured the image of a metaverse reminiscent of Ready Player One, a (granted, commercially stratified) world where we choose how we appear to one another, and our avatars interact in ways reminiscent of the “real” world, but freer.

There are some considerations to take into account. Since both Microsoft and Meta imagine that the first phase of the metaverse will be related to work, how we appear in these new virtual environments will likely take on a different quality than our in-game or social avatars. To make the promise of a metaverse worth the investment these companies are making, they must simulate lifelike experiences of human interaction.

This means a new breed of realistic avatars that can, for instance, represent our unique gestures and moods. Google’s patent for facial expression tracking in augmented reality is one example of the push to conquer this space. If successful, such technology can be as transformative as digital twins have been in the real estate sector.

These are just a few among many examples of companies creating lifelike virtual copies of physical things (including us). Volograms, for example, creates 3D recordings of users that can be used in mixed reality.

In a way, big data has always provided the contours of a self that exists in parallel to us. Most data is generated through continuous mundane activities—such as paying for something, driving, messaging or watching TV—creating an idea of a person, with certain affinities and habits, that is not so much you as you-ish. Tech companies have struggled to transform these data sources into a single coherent image of us.

But avatars can easily become focal points for digital data, especially as they link to devices that help them mimic real-life facial expressions or emotional states. Apple’s custom avatar emojis are an early-stage precursor of this.

Contrary to the imagery conjured by Zuckerberg's presentation, it is unlikely that the Metaverse will remain completely separate from offline reality. Mixed-reality devices, such as AR smart glasses that display contextual information, have higher potential for adoption—precisely because of their potential relevance to our everyday lives.

The case for data ownership

Now we return to the question of whether we have a tacit right to our data. It seems intuitive that my data should belong to me.

Conceptualising such a right immediately courts several difficulties. For one, the definition of property, used by legal systems around the world, does not generally allow data to be considered in terms of ownership because of difficulties in establishing exclusivity. In essence, for our claim to ownership of a good to be recognised, the good must be specific and limited—in other words, my exclusive right to use or possess this good must meaningfully restrict the rights of others.

Data isn’t like this. Data is unlimited, and typically only exists thanks to multiple parties participating to generate, enrich and define it. Thus, many legal scholars argue that the concept of data ownership is simply moot.

This is why, in the EU—which arguably has one of the most stringent data regimes—access to personal data is regulated through privacy rights, where control of personal data is ceded by the consumer to technology companies and other third parties, including the government, based solely on consent. In other words, European users can “opt out” of services that rely on data collection, and have the right to be forgotten—in other words, to demand that any company holding their personal data must erase it.

The level of privacy Europeans enjoy is based on a tradeoff that we are willing to make between privacy, convenience and safety.

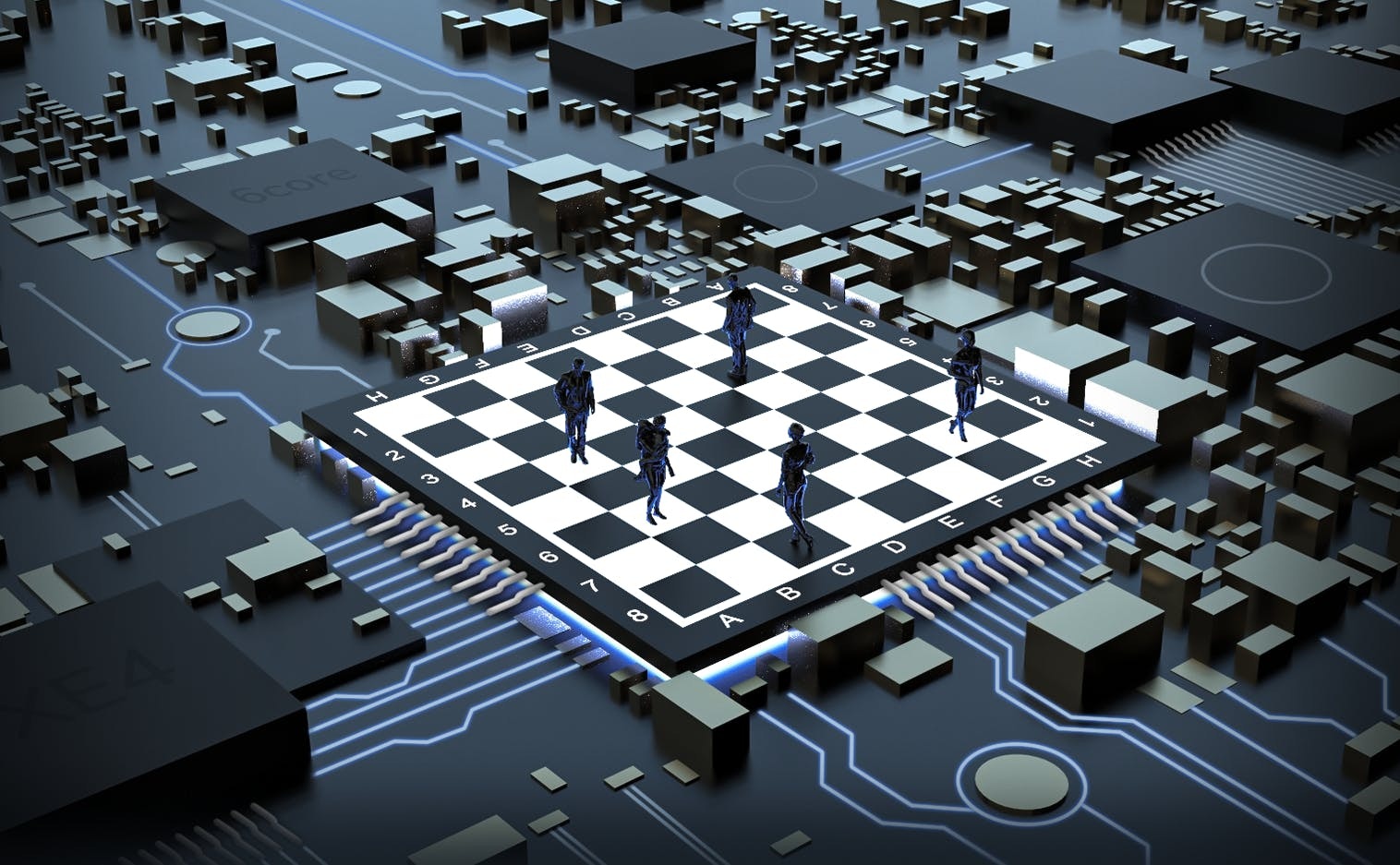

But the belief that individuals can opt out of data-dependent services is little more than wishful thinking. In a digitalised reality, the disproportionate power dynamic favouring data controllers over citizens makes it hard to see how privacy can be a choice. Since data is stored and analysed in a manner inaccessible to us, we often aren’t even aware of who knows—or simply holds—certain information about us.

This approach to personal data neglects a different intuition that may be behind the desire for data ownership: We understand ownerships of ourselves as a form of authorship.

Authorship is central to western ideas of self-ownership. It allows us to believe we are partly or completely in control of who we are, have the ability to transform ourselves and choose how we wish to appear to others.

But our growing digital trails threaten our ability to choose our own self-image. Perhaps as importantly, it creates a type of determinism that might threaten assumptions we have about what it means to be the author of one's fate. In the end, insofar as we are collections of data, we also appear to be quite predictable.

What’s more, the more of our lives are digitally paralleled, the easier it is for state and non-state actors to consider investing in modes of surveillance and other forms of social control. The case for data ownership becomes not only an attempt to seek equity in the corporate profits coming from big data, advertising or virtual reality—but a plea, central to maintaining key aspects of the liberal democratic society, such as personal autonomy.

Where ownership and privacy clash

There are risks to trying to regulate data ownership. According to Privacy International, establishing data as personal property would likely not lead to greater individual control of it. In one of their Future Scenarios on Data Property reports, the organisation argued that “Property usually comes from an approach of non-disclosure, not one where you want to disclose by default.”

The authors observe that even if individuals did want to exercise ownership rights and prevent companies from acquiring their data, they would be at an acute power disadvantage, given that so many services rely on data-sharing.

What’s more, having data property rights would make us more likely to sell our personal information. This already happens when we choose to share data in exchange for access to a “free” service. At the extreme end, celebrities like Snoop Dog actually make money by bringing digital copies of his home to the Sandbox—just so fans can pay to spend time in it.

Protecting the choice of how we appear to others

Given the friction between data ownership and privacy, we should see an entirely new industry emerge—from advanced privacy solutions, private data custody, litigation and insurance—to AI advisors that help manage access to our data in ways that are effective and beneficial to us.

But there is also hope that we can solve some of these issues by ensuring that privacy and control over data access is central to the digital and virtual services we design. We know that this can be achieved because we have done it before.

Open Banking, a financial and payments initiative in a number of countries, including the UK, Japan, EU and the US, is one example of privacy by design. The scheme, driven by regulations in the UK and Europe, obliges banks to provide APIs to consumer-authorised third parties in order to access our financial data, or even make payments. Within Open Banking, data is shared in a way that prevents third parties from using it beyond the scope of what the consumer has authorised.

The question remains of who will drive regulation of data ownership and privacy in the new digital frontier. EU institutions seem to be leading the push—but remain behind the capabilities and problems that we already see emerging from new technologies.

For now, we may need to buckle up and get used to living in the digital Wild West.

11 Aug 2022

-

Michal Rozynek

Illustration by Debarpan Das.

Get the future in your inbox.

02/03

Related Insights

03/03

L’Atelier is a data intelligence company based in Paris.

We use advanced machine learning and generative AI to identify emerging technologies and analyse their impact on countries, companies, and capital.